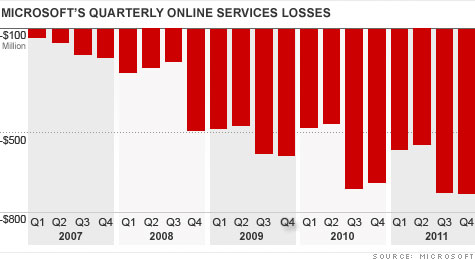

NEW YORK (CNNMoney) -- Bing, Microsoft's two-year old search engine, is losing nearly a $1 billion a quarter, with no sign of letting up.

Microsoft (MSFT, Fortune 500) has lost $5.5 billion on Bing since the search service launched in June 2009, but the company's search losses actually pre-date that. In fact, the software giant has never made money in its online services division. Since Microsoft began breaking out that unit's finances in 2007, the company has lost a total of $9 billion.

Even the good news with Bing isn't so great. Microsoft proudly proclaims that it has gained search market share against Google (GOOG, Fortune 500) in each of the past 27 months. While that's true, it is not gaining search share from Google.

Bing currently maintains a 14.7% share of the search market, up from 8.4% when Bing launched, according to online data tracker comScore (SCOR). Google currently commands 64.8% of the market -- down just two-tenths of a percentage point from the 65% it held when Bing debuted.

More than half the share that Bing has gained has actually come from third-place Yahoo (YHOO, Fortune 500). The rest has come from search cellar-dwellers Ask.com and AOL (AOL).

There's usually no such thing as "bad" market share growth, but Yahoo's search is powered by Bing. That means more than half of Microsoft's share growth has come from cannibalizing its search partner.

Can Bing escape its stagnation and actually make money? Microsoft says it has a solution.

At the company's financial analyst meeting in Anaheim, Calif., last week, Microsoft President of Online Services Qi Lu gave an impassioned speech about how Bing would improve search by "reorganizing the Web." To do that, Microsoft plans to leverage its network of products and partnerships to gain a better understanding of what the user is after when they enter a query into a Bing search box. Ultimately, Microsoft believes its technical secret sauce will let Bing both expand what is "searchable" and deliver more robust search results than any of its competitors.

Lu said Microsoft could not and would not try to "out-Google" Google. Instead, it must "change the game fundamentally."

Bing has already begun to show some of that capability. For instance, though partnerships with various ticketing agencies, a search for "Mariners tickets" will display links to upcoming games and a map of Seattle's Safeco Field showing fans where tickets are available. A search for flight information will tell you when the best day is to purchase a plane ticket. Searching for "digital camera" will display images of cameras that can be filtered, sorted and compared.

It's a step forward from a laundry list of blue links.

Through its search partnership with Facebook, its mobile partnership with Nokia (NOK) and its marriage with various Microsoft products, Bing will gradually gain a semantic understanding of the Web, Lu said. That will transform search from today's noun-based keyword entry -- a system Lu dismissed as "caveman speak" -- to eventually give Bing the ability to field questions phrased in natural human language.

It sounds great. But how is this thing going to make money?

Stefan Weitz, Microsoft's director of Bing, believes that if Bing can change the way people think about search, sooner or later users will switch over from Google.

"Our challenge is that no one wakes up in the morning and says, 'I really wish there was a better search engine,'" Weitz said. "That's why, for us, it's always been about figuring out how to accomplish more than we thought was possible with a search engine. Eventually, people will expect to do more with search, and if they can't, they'll be disappointed."

Luring users away from Google is a daunting task. Microsoft is competing against a verb -- "I'll go Google that" -- and an entrenched consumer habit.

Even if Microsoft can steal market share from Google, it faces a long journey toward profitability. Market share is key in search: With it, advertisers flock to you, and you can charge high rates for ads. But without it, search is a very expensive business.

To capture the attention of a critical mass of advertisers -- enough to turn a profit -- multiple analysts said that Bing will need at least 25% to 30% of the market. That's double its current share.

Meanwhile, Google is also scrambling to -- as Microsoft put it -- "do more with search." Google recently launched a new social network, integrated advanced flight data into its search results, and tweaked its algorithm to favor original content.

Weitz calls the Bing-vs-Google rivalry a "big geek slap fight," and says Microsoft has one key advantage over its rival: It has nothing to lose by experimenting. On the flip side, slight tweaks to Google's search algorithm send shivers down the spines of companies that rely on high rankings.

"We are able to try things with much more flexibility," said Weitz. "If we make a mistake, it's not going to take down the company."

Most analysts are bullish on Bing's technology, but they're mixed on whether Internet users will really change their behavior.

"Bing will likely be better than Google over time, but even if it is, users and advertisers still need to go to them," said Sid Parakh, analyst at McAdams Wright Ragen. "To be clear, this will take a long, long time to play out. This is something Microsoft will continue to lose money on."

Several analysts, including Parakh, predict that Bing will continue to incrementally improve and gain share, becoming profitable in another three to four years.

Looking at Google's dominance, it may seem impossible today for a rival to get a significant foothold. But the tech world is funny like that: No one could have imagined 13 years ago that a small search engine out of Stanford University would ever unseat the mighty Yahoo.

"When you're talking about something like consumer behavior and advertising, having the advantage of being the first place people go is hard for another company to counteract," said Sue Feldman, search engine analyst at IDC. "Can it change? Sure. As with everything in technology, in a period of tremendous ferment and innovation, something could happen to overturn a market leader." ![]()