Walmart's "disc-to-digital" program uses UltraViolet, a service that the movie industry is pushing.

NEW YORK (CNNMoney) -- Walmart unveiled a "disc-to-digital" service Tuesday that lets customers buy online access to movies they've already purchased on DVD or Blu-ray.

Customers can take their discs to a Walmart (WMT, Fortune 500) store and pay $2 for online access to a standard-definition copy of the movie, or $5 for high definition. The program launches on April 16 in about 3,500 Walmart stores.

The new program "allows customers to reconnect with the movies they already own on a variety of new devices, while preserving the investments they've already made in disc purchases," Walmart executive John Aden said at a press conference Tuesday.

Walmart's program uses UltraViolet, a service that the movie industry has been pushing.

Unlike services including Apple's (AAPL, Fortune 500) iTunes, UltraViolet doesn't store actual content in the cloud. Instead, when users buy movies, a "digital proof-of-purchase" is added to their personal UltraViolet accounts. It's essentially a library of licenses.

Each account holder can then download or stream those movies on up to 12 devices -- including tablets, TVs and phones. A single account can be shared between up to six people.

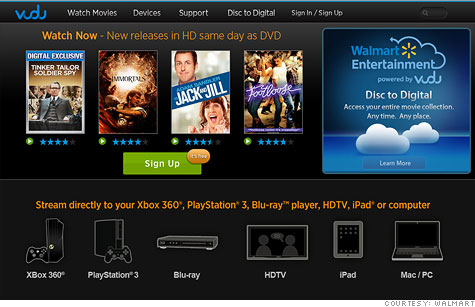

Users can watch the movies through a handful of sites or services. In Walmart's case, it's powered by Vudu: A streaming service the retailer bought in 2010 and uses for its online video-on-demand offering.

Tuesday's announcement included a handful of studios -- Fox, Sony, Universal, Warner Brothers (which is owned by Time Warner (TWX, Fortune 500), the parent company of CNNMoney) and Paramount -- that also back the UltraViolet service.

In January, Amazon (AMZN, Fortune 500) became UltraViolet's first retail partner.

Industry push for UltraViolet: UltraViolet, which launched in mid-October and is still in beta testing, is the industry's attempt to solve the problems surrounding digital rights management (DRM) -- which is only getting tougher as owning multiple devices becomes the norm.

The service is the brainchild of the Digital Entertainment Content Ecosystem, a consortium of scores of companies with skin in the game: Internet service providers, studios, hardware makers and more.

The future of their industry depends on getting the digital piece right. But UltraViolet has been slow to take off. After all, it caters to people who have libraries of physical discs. Is that really the demographic that's likely to stream movies on a tablet?

The service's success also depends on customers' willingness to pay a premium for owning, rather than streaming, a movie. People could pay Walmart $2 to $4 for the digital license of one movie; or they could buy a Netflix (NFLX) streaming account for $8 a month.

Retailers peddling the service will have to work hard to convince customers that they're not paying "extra" for content they already own.

In fact, when UltraViolet first launched, it appeared the service would be bundled in with a DVD or Blu-ray purchase. The first UltraViolet DVD was Warner Bros.' October release of "Horrible Bosses," which simply came with a code for a digital license for no extra charge.

But UltraViolet's evolution over the past few months shows that UltraViolet's backers have no intention of handing over digital licenses for free. ![]()