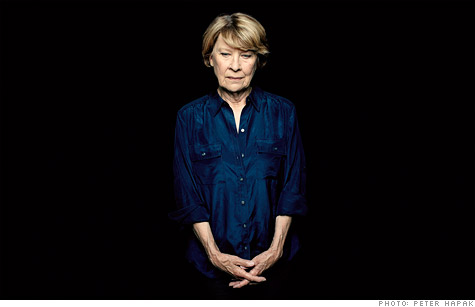

A controversial Medicare billing practice cost Laraine Sickels $7,000.

(MONEY Magazine) -- After Laraine Sickels, a retired teacher from Whidbey Island, Wash., fell outside a friend's house last summer, she lay on the ground in excruciating pain, unable to move.

Rushed by ambulance to Providence Regional Medical Center Everett on that Thursday morning, she learned that she had three breaks in her pelvis. By Monday Sickels, now 71, was cleared to leave the hospital for a skilled nursing facility, where she'd get physical and occupational therapy.

That's when the pain spread from her hip to her wallet. Medicare fully covers 20 days in a skilled nursing facility as long as you've spent three days in the hospital as an inpatient (among other criteria). Sickels, though, didn't meet that standard.

For four nights and five days, she had slept in a hospital bed and donned a hospital bracelet while doctors ran tests and prescribed medications. Yet she'd been held under observation, a designation intended for patients who aren't ready to go home but don't need as intensive care as a fully admitted patient does. And with Medicare, observation services don't count toward rehab coverage.

Sickels' tab for her 10-day stay: $7,027.

"I'm frustrated and angry. The situation is ludicrous," says Sickels, who is back on her feet but still fighting Medicare. (See our companion piece Medicare: Avoid big rehab bills, on how to negotiate your bill.)

While not commenting on Sickels' case, Joanne Roberts, the hospital's chief medical officer, says it's common for an otherwise healthy pelvis-fracture patient who doesn't have surgery to stay on observation.

Sickels' story is an increasingly familiar one. Medicare pays hospitals far less for observation than for inpatient stays. As Medicare seeks to cut costs, a growing army of auditors use an automated screening system to second-guess admissions. A hospital that gets dinged commonly loses all its revenue for a stay.

Result: Medicare patients are going to the hospital with anything from chest pains to seizures and spending days under observation, at times to the dismay of physicians -- and in contradiction of Medicare's own guidelines.

In 2009, the most recent data available, observation stays topped 1 million, up 25% from 2007, according to a study published in June by researchers at Brown University. Half were for longer than a day and about one in seven lasted longer than 48 hours, yet Medicare says most observation stays should last no more than 24 hours and only "in rare and exceptional cases" go beyond 48.

Doctors say observation patients typically get appropriate treatment in the hospital. At stake for you or a parent is something you'll often learn about as you leave, or when you show up at rehab: a tab for follow-up care that can run into four or five figures.

Says Alice Bers, an attorney with the Center for Medicare Advocacy: "What seems like it should be a technical billing issue has turned into something that can have pretty disastrous financial consequences."

Here's how this bureaucratic trap springs, and what you can do to try to avoid it or steer a family member around it.

The price of no admission

For decades hospitals have used the middle ground of observation when a doctor can't confidently okay your release but isn't sure you're sick enough to be admitted. Typically you're watched and treated for up to a day until the doctor can make the call.

A classic example, says Thomas McCarter, chief clinical officer for Executive Health Resources, which advises 2,100 hospitals on Medicare compliance, is someone who goes to the emergency room with chest pains. Often the initial tests come back normal. But, particularly with seniors who have other risk factors, the patient might be on the verge of a heart attack. So in that case a doctor would run tests every eight hours until the diagnosis becomes clear.

The consequences of resorting to observation more often have hospitals, doctors, and patient advocates sounding alarm bells. Last November the Center for Medicare Advocacy and the National Senior Citizens Law Center filed a lawsuit against the Department of Health and Human Services on behalf of seniors (now a total of 14) challenging the use of observation.

A Medicare spokesperson, while not commenting on the suit, says the agency continues to monitor the trend to ensure that patients get the care they need.

Where you'll spot the difference

You might never notice that you haven't been admitted. "From the physician perspective, whether you're inpatient or observation doesn't change what we do for you," says Larry Hegland, chief medical officer at Ministry St. Clare's Hospital in Weston, Wis.

If you're 65 or older, where you'll see the difference is on your bill (with private insurance, including Medicare Advantage plans, you may not pay any more).

Under traditional Medicare, an inpatient hospital stay, including drugs, is covered under Part A. You'll owe a fixed deductible, $1,156 in 2012, for a stay of up to 60 days.

Observation care falls under Medicare Part B, the insurance for doctor visits and tests you get as an outpatient. With Part B, you typically owe 20% co-insurance or a co-pay (after a $140 deductible) on each service. That could mean a higher bill than what you'd face as an inpatient, says Richard Pinson, an MD at hospital consultant HCQ Consulting.

Drugs, in particular, can add up since hospitals typically charge far more than retail, and your prescription plan (Part D or a supplemental policy) may not cover the pills the hospital hands you. Sickels was billed $10 for a single cholesterol pill, and her five-day total for drugs was $531.

Why rehab does the biggest damage

Hospital bills, though, usually pale in comparison to the shock you'll receive if you transfer to skilled nursing care. Patients who spend three consecutive days (not counting the day of release) as a hospital inpatient pay nothing for the first 20 days and then $144.50 a day for days 21 to 100.

Coming from observation, you'll get socked with the full rate. And because supplemental policies kick in only when Medicare does, you'll get no help there either. Even if you're switched to inpatient later, the observation days don't count toward the three-day rule.

After tripping while getting off an elevator, 92-year-old Lois Frarie, from Monterey, Calif., spent four nights at Community Hospital of the Monterey Peninsula with a broken pelvis and elbow.

Initially admitted as an inpatient, according to her medical records, her status was reversed a day later, so her first two days were considered observation. Only on the third day, when she had surgery, did she cross to inpatient status.

The price of being one day short of the threshold: $20,000 for nearly three months in rehab. Had the inpatient label stuck from the get-go, according to Pacific Grove Convalescent home, she wouldn't be out a dime, since she has a supplemental insurance policy too.

Many argue that the decades-old three-day rule is ripe for elimination, since medical advances have shortened hospital stays. The American Medical Association has called for it to end; in May, Medicare told the AMA in a letter that the agency hasn't found a way to do that under current law.

Medicare does not require hospitals to tell you your admission status, except when you're transferred from inpatient to observation. "People are told as they leave the hospital to bring their checkbooks to the nursing home," says Toby Edelman, an attorney at the Center for Medicare Advocacy.

Faced with unaffordable bills, some seniors forgo needed care altogether, says Elise Smith of the American Health Care Association, a nursing home trade group.

What's behind the rise

To understand why you could end up spending days under observation, it helps to know a bit about the financial forces at play. Chief among them: Medicare's attempt to cut down on fraud and overpayments by stepping up claims auditing.

Four recovery auditing firms now take a second look at hospital, doctor, and other bills (earning 9% to 12% commissions on what they recover). Since late 2009, when the program went national, Medicare has collected $1.9 billion in overpayments through these audits.

One area the auditors have zeroed in on is the gray zone between inpatient and observation. The reason: Because the care you're given is less intensive, the amount that Medicare reimburses for observation is typically far less.

Spend a night in the hospital for chest pain, and Medicare might pay the hospital $4,100 if you're an inpatient, $1,800 if you're on observation, says Sandra Routhier, a consultant for Panacea Healthcare Solutions. When an auditor rules that an inpatient stay should have been observation, the hospital typically loses the entire Medicare payment.

Those denials can take a toll on a hospital's balance sheet. Earlier this year the Office of Inspector General, which also examines Medicare bills, said that $576,927 worth of inpatient care at Georgetown University Hospital should have been billed under Part B. (According to the report, hospital officials chalked up the errors to residents and trainees misunderstanding the criteria; Georgetown declined to comment.)

Hospitals on the defensive

The decision to admit you isn't always crystal clear, and Medicare offers only broad guidelines.

"Two different sets of eyes looking at the same data may make different calls," says Eric Coleman, director of the care transitions program at the University of Colorado.

Faced with the prospect of having to eat the entire cost of a hospital stay, institutions are often erring on the side of watch and wait. "Hospitals are taking the observation payment, even though it's lower, instead of rolling the dice to see if they get the full inpatient fee," says Coleman.

Anthony Chavis, vice president of medical affairs at Community Hospital of the Monterey Peninsula, where Frarie spent days under observation before surgery, likens the dilemma to the 55-mile-per-hour speed limit.

"If we go 56 and designate the patient inpatient who should have been observation, the government is concerned you might be defrauding them," he says. "If we go 54, the patients may pay a toll in higher bills and the hospital in lower reimbursements."

Who really decides your fate

On paper, a doctor decides whether you should be admitted to the hospital or kept on observation. In practice, the admitting doctor, often a so-called hospitalist, makes the initial in or out call.

Then, per Medicare rules, your records head to a case manager, who confirms the decision or tells the doctor the guidelines haven't been met (in that case, one or two other doctors may be roped into the decision to switch).

Behind the curtain

Because Medicare regulations are so short on specifics, the hospitals making the admission decision have come to rely on the same tool that the auditors reviewing that call down the road check with as well: screening programs created by private firms.

Medicare requires hospitals to use some type of screening process, though it doesn't endorse a particular one. But the most common screening tool is InterQual, owned by McKesson. Behind InterQual's black box is a team of almost 30 doctors and nurses, who pull research from medical journals and consult with a panel of physicians and clinical experts. Factors such as patient age, medical history, and underlying conditions are baked into the formulas.

These algorithms don't please all doctors. J. Jeffrey Marshall, president of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, says his group believes that in certain cases an angiogram should qualify for inpatient, yet the screening tools say otherwise.

"Part of being a doctor is giving the right treatment to the right patient at the right time," he says. "You can't cookbook that." Another doctor beef: Auditors have the benefit of hindsight.

Laura Coughlin, vice president of InterQual development and clinical strategy, says that the company simply offers guidelines to doctors. Ultimately, though, her team makes a judgment call that can be costly for a hospital to ignore. "At the end of the day our criteria have to come down to a decision, not just be fluffy and left to the end user to figure out," she says. "That's part of the secret sauce of InterQual."

Why fighting back is tough

You can appeal a nursing home bill, but it's tough to know where to begin. In its lawsuit, the Center for Medicare Advocacy is pressing for an immediate appeals process that's clearly outlined. In court filings, Medicare has said that an adequate process exists.

Mary Smith of Middletown, Del., whose 86-year-old mother is a plaintiff in the lawsuit, is six months into her appeal of a $10,600 rehab bill. She's found the system nothing but frustrating.

One letter from Medicare suggested she have the hospital change her mother's six-day stay to inpatient services, something hospital officials told her they can't do after the fact.

Patty Resnik, the corporate director of quality and utilization management at Christiana Care Health System, says they have sent the Medicare letter on to a local Medicare office. "We are bound to comply with Medicare rules, which may place a burden on patients," she says. "We empathize." Thus Smith remains stuck in a web of bureaucracy. As she's learned, "No one will touch observation."

More on this story: Medicare: Avoid big rehab bills ![]()

Carlos Rodriguez is trying to rid himself of $15,000 in credit card debt, while paying his mortgage and saving for his son's college education.

| Overnight Avg Rate | Latest | Change | Last Week |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 yr fixed | 3.80% | 3.88% | |

| 15 yr fixed | 3.20% | 3.23% | |

| 5/1 ARM | 3.84% | 3.88% | |

| 30 yr refi | 3.82% | 3.93% | |

| 15 yr refi | 3.20% | 3.23% |

Today's featured rates: