|

How to plug your company's brain drain When workers retire, they take critical know-how out the door. But one government agency found a better way to pass it on.

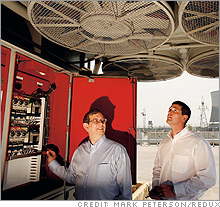

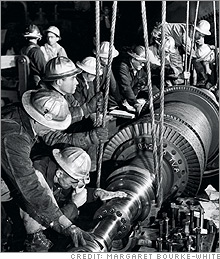

(Fortune Magazine) -- In the switching yard at Sequoyah Nuclear Plant, about 20 miles outside Chattanooga, stand eight gigantic transformers. The huge machines, which weigh nearly 700 tons each and dwarf the hard-hatted humans working on and around them, take power from Sequoyah's nuclear generators, ramp it up to 160,000 volts, and send it out to the Tennessee Valley Authority's grid, which spans five Southern states. "If the transformers fail, you're not putting out any power," says Dave Stinson, 26, a senior electrical engineer whose job it is to make sure that doesn't happen.

Keeping entire counties from plunging into darkness is a lot of responsibility for somebody just five years out of college, but Stinson learned how to do it in large part by spending several months working cheek-by-jowl with a 33-year veteran engineer named Lamar "Butch" Woodley. Invaluable knowledge transfer As Woodley and the TVA's other longtime technical experts retire, they won't be leaving young employees like Stinson in the dark. That's because the TVA began several years ago to tackle a problem most big U.S. employers are only now beginning to ponder: an aging workforce that, within five years, will begin taking enormous amounts of critical know-how out the door. We've all seen the statistics. The oldest of 77 million baby-boomers turn 60 this year. Indeed, someone in the U.S. turns 60 every seven seconds. By the end of the decade, the Conference Board reports, 40% of the workforce will be eligible to retire. And even though surveys show that 70% to 80% of executives at big companies are concerned about the coming brain drain, fewer than 20% have begun to do anything about it. Even within that small forward-looking cadre, many seem to be counting mainly on enticing older workers to stay longer than they have to, or to "consult" after they retire. "Companies know there is a looming 'wisdom withdrawal,' but they're putting off addressing it," observes William Arnone, an Ernst & Young human-capital consultant. He worked on a recent survey of large employers that showed that 70% haven't even begun to identify what wisdom they'll need to keep, let alone how. When they do, a close look at how the Tennessee Valley Authority (Charts) is dealing with the problem might come in handy. The approach is refreshingly straightforward and travels well: John Deere (Charts),Chevron (Charts), and the World Bank, among others, have already adopted many of the TVA's methods. Starting in 1999, the TVA broke down the daunting task of retaining knowledge into manageable parts, by asking line managers three questions:

Critical employee communications Of course, to get a grip on where in the organization the brain drain is likely to hit first, it helps to know when people are planning to retire. "We knew that one-third of our engineers and technicians would probably retire within five years, but we didn't know who was thinking of leaving when," recalls HR chief Phil Reynolds. So he and his staff did something very few employers do: They asked. The first time the TVA sent out its when-are-you-retiring questionnaire to all 13,000 employees, only about 40% responded, but after a communication blitz to convince employees their answers weren't binding, the response rate jumped to 80% the second year, and now it is virtually 100%. Based on those survey results, the TVA gives each employee a score of 1 to 5, with 1 denoting a person who doesn't plan to leave for six years or longer, and 5 earmarking someone who will be gone within a year. Meanwhile, managers and supervisors assign the people reporting to them a second score of 1 to 5, this one reflecting how essential their knowledge is to the power plants' operations, with a score of 5 being the most critical. Once you've multiplied everyone's attrition score by his critical-knowledge score, you get a vivid snapshot of where to take immediate action. For instance, if you have a nuclear engineer who plans to retire in six months (5) and take with him decades' worth of arcane knowledge (5), that person gets a 25 - a big red flag. "It gets top management's attention," says former TVA workforce planning manager Ed Boyles, who recently retired himself. "If you say, 'This site has three engineers with scores of 20 or higher,' then it's pretty clear you have to get busy right now." The third part of the process ("Now what?") is getting people to pass on what they know. Some information is easy to pass on: say, whom to call at GE (Charts) when a turbine is acting up. Harder to replace is "tribal knowledge," which typically not only is undocumented but tends toward the indescribable. The TVA had a steamfitter foreman at one plant, for instance, who over many, many years had developed an uncanny knack for detecting corrosion inside feedwater pipes by tapping on them with a wrench and listening for a particular sound. In that case the TVA assigns a younger engineer to shadow the older one. These apprenticeships can also be a recruiting draw because they allow younger workers a chance to move up the ranks fast: Stinson, for example, had lots of job offers when he graduated from Albany State University in Georgia in 2001, but signed on with the TVA because he wanted a shot at a big job quickly. He was promoted to senior engineer last year. Indeed, over the past five years 32% of the TVA's workforce has retired and been replaced, with nary a glitch in operations. Five years from now, will your company be able to say the same? In the ten minutes it may have taken you to read this, 90 more boomers turned 60. _____________________________ Related: From the July 24, 2006 issue

|

|