The battle over your aching back New alternatives to surgery are gaining favor. Here's a look at the best treatment options.

(Fortune Magazine) -- John Chiota was ready to try just about anything. After a 2001 car accident, Chiota, a 63-year-old Connecticut lawyer and probate judge, had lower back pain so bad that he often had to hear cases while standing up. Simple tasks like shaving were agony. Physical therapy didn't help. Painkillers worked for a while but then wore off. His doctors suggested surgery but could not guarantee that it would help. Chiota was about give the local acupuncturist a call when he heard about Norman Marcus, a psychiatry and anesthesiology professor who runs a small, private - and controversial - pain institute in Manhattan. "I knew it was off the beaten path," Chiota recalls, "but at that point, I didn't care."

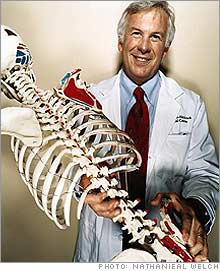

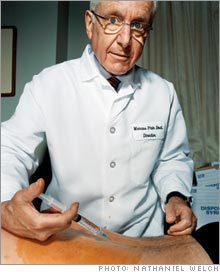

Ten days after seeing Marcus and submitting to his therapy, in which he uses a needle to break up knotted muscle tissue - "trigger points" - Chiota was pain-free. Still, he admits Marcus is not for everyone. "He is not a quack, but he's not mainstream," Chiota says. "There are not a whole lot of guys like him." Maybe not, but the ever-growing ranks of back pain patients have more alternatives to surgery than ever before. That's a good thing, since more than 70% of adults - including hordes of desk-bound business executives - will have back pain at some point in their lives; it's the second most common reason for doctor visits in the U.S., according to the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. In 2001, the World Health Organization declared lower back pain an official epidemic. It's a costly one. A Duke University study found that treating back pain costs Americans more than $26 billion a year, or 2.5% of our nation's total health-care bill. Much of that spending is devoted to the 10% or so of back patients who suffer from chronic, debilitating pain, like Chiota. For those poor souls, determining the precise cause of their pain is a frustrating maze of X-rays, MRIs, and CT scans. That's because the anatomy of the lower, or lumbar, spine - an intricate assemblage of bone, muscle, nerves, shock-absorbing disks, and ligaments - is much more complex than, say, that of the knee or hip. In a structure so complicated, there are a lot of things that can go wrong. Pain in the lower back can result from multiple factors: mechanical, neurological, even psychological. Which helps explain why in a shocking 85% of cases, according to one researcher, doctors can't pinpoint why a person hurts. There's still no proven consistent way to treat chronic lumbar pain, although there is a growing consensus against invasive, expensive surgery - and it's one shared even by some surgeons. Still, there's plenty of debate and confusion out there and any back pain sufferer trying to pick his way through the rival camps of surgeons, doctors, chiropractors, physical therapists, and pain specialists needs all the advance intelligence available. The following is a field guide to the kinds of professionals patients are likely to meet in their quest for relief. As representatives of the various camps, we'll meet four medical men, each of whom has dedicated his life to a different treatment method. At the outer limits of the back world are people like Marcus, loved by his patients, but denounced by fellow MDs. Orthopedic surgeons and chiropractors make up the standard approach - although chiropractors themselves were not long ago regarded as charlatans by the medical establishment and even now, many MDs do no more than tolerate them. Trying to make sense of all these competing treatments and theories is a surgeon and researcher at Dartmouth, James Weinstein, who is leading the biggest-ever U.S. study of back surgery. His intention is to finally come to some definitive conclusions about what really works and what doesn't. He's finding, however, there are more forces than just mere science driving the battle over how to heal your back. On Sept. 26 in Seattle, two thousand members of the North American Spine Society (NASS) will gather for its annual meeting. A boring affair, one would guess, replete with tedious recitations of arcane medical studies, tall tales from the golf course, and rubber chicken. Think again. This year's confab will feature the unveiling of early results from a massive six-year, $13.5 million study, conducted coast to coast in 12 locations and funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The study, dubbed SPORT (Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial), seeks to answer the most vexing question in back pain treatment: To cut, or not to cut? Heading the study is Weinstein, chairman of the department of Orthopedic Surgery at Dartmouth's Medical Center and editor-in-chief of the journal Spine. He's also an advocate of nonoperative back treatment, and thus is something of a pariah among many of his fellow surgeons. That doesn't bother Weinstein. What does bother him, he says, is that when "a patient puts his spine in my hands," he cannot say what results to expect. "We have failed in this basic principle." Back surgery's frequent failure Saying that back surgery can be a roll of the dice is not far from the truth. Last year there were 1,175,000 inpatient spinal surgeries in the U.S. alone, according to market research firm Spinemarket and newsletter Orthopedic Network News. The best surgeons claim that 80% of their cases are successful, but "success" is a pretty nebulous concept. Most surgery patients still have some pain postoperatively. Failure is so common, meanwhile, that a term, "failed-back-surgery syndrome," has been coined to account for it. Who's to blame? On one side are surgeons who are too quick on the trigger. "Lots of back operations continue to be done with a shotgun approach," says Edward Hanley, chair of the Department of Orthopedic Surgery at Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte. But the desire of surgeons to operate is only part of the problem. The severity of chronic back pain leads many long-suffering patients to eschew conservative treatment and seek a quick fix in the operating room. "Patients' expectations these days are very, very high," says NASS president Joel Press. To try to ground those expectations in hard data, SPORT's research team has recruited some 2,500 patients to gauge the efficacy of surgical vs. nonsurgical treatment for three common back disorders. The fireworks started early. "The SPORT study seems to announce a preconceived bias against operative care," wrote the NASS board of directors in 2003. Their major beefs regarded patient-selection criteria and the clinical design of the project, "which inappropriately favored nonoperative treatment," according to the American Association of Neurological Surgeons. "It's the first time that I am aware of that people have criticized a study before it came out," says Weinstein. "I didn't expect that." He should have. Tangling with spine surgeons can be hazardous to your health. In the mid-1990s, when the federal government tried to issue guidelines for treating acute back pain, the surgeons complained loudly. Sofamor Danek, a medical-device company (now part of Medtronic (Charts)), even sued to suppress the recommendations. "Some companies are afraid of the results of [SPORT]," says Frank Phillips, an orthopedic surgery professor at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago. Weinstein admits that he was "naive" about the fact that "there are other interests at stake." In June, Weinstein released the first set of SPORT data, for herniated-disk procedures, at a meeting of the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine in Norway. To the relief of the surgeons, the data supported surgery for the ailment. "I don't care what the results are," Weinstein says. "What I am really interested in is the truth." But if there is - arguably - too much back surgery in general, the conventional medical wisdom has shifted away from the knife somewhat in recent years. Launched in 1978, the Texas Back Institute represents the establishment approach to treating back pain, one that has evolved to encompass a host of disciplines. In its early days TBI had just three surgeons and nine employees, but today its 204 staffers include physiatrists, psychologists, pain specialists, chiropractors, and physical therapists. Every year TBI handles more than 55,000 patient visits, and its 11 surgeons perform about 2,000 surgeries. (That may sound like a lot, but only 11% of TBI's patients actually go under the knife.) The man minding this one-stop shop for back care is president Richard Guyer, a surgeon and one of TBI's three co-founders. TBI's soup-to-nuts approach to back treatment makes sense - if the chiropractor can't help you, he'll send you down the hall to the pain specialist, or maybe to the psychologist for some hypnotherapy. Surgery is a last resort. (One procedure done at TBI involves implanting artificial disks.) But the setup also exposes the rifts that exist between various camps, including those forced into uneasy alliances. For instance, one minute a TBI chiropractor is praising spinal-decompression therapy, a new treatment - inspired by NASA - that involves reducing pressure on the spine to heal the spongy disks that sit between the vertebrae. The next minute, a TBI surgeon derisively dismisses the technique. If these guys are together in one big tent, it's only because none of them can claim to have a proven solution. Guyer is realistic and even humble about that state of affairs. "Back pain is an enigma," he says. "We do the best we can." If TBI is a back-repair department store, chiropractor Doug Seckendorf's Manhattan practice is a high-end boutique. Seckendorf's clientele includes Blackstone Group co-founder Pete Peterson and, reportedly, KKR kingpin Henry Kravis and former Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin - people who cannot afford to be laid up for weeks after back surgery. (Seckendorf's staff even makes house calls in the Hamptons.) Complementary medicine can reduce pain Twenty-two million Americans see chiropractors each year, and it can be effective in relieving acute pain. The mainstream medical community has grudgingly come to accept it - TBI, for example, added chiropractors nine years ago. But some older MDs still think it's quackery, mindful of a few overeager chiropractors who once claimed to be able to cure everything from diabetes to cancer. Seckendorf makes no such rash claims. His practice, Manhattan Sports Medicine, includes nutritionists and massage therapy, but the bulk of the work takes place on his $15,000 chiropractic tables. "We're intense," he says. "We put you on a table and pull you apart." Clients also sweat through workouts in a small gym under the guidance of exercise physiologists. For this they pay $450 for an initial visit, and $155 after that. Seckendorf doesn't accept insurance, but his rich clientele doesn't seem to mind. Nearly a decade ago, Pete Peterson started having a good deal of back pain. An MRI test found spinal stenosis, a narrowing of the canal the spinal cord runs through, and an orthopedic surgeon recommended surgery. Seckendorf says this rush to judgment is common: "There's a fair amount of impulse buying in spine surgery, where the patient just wants to be out of pain." But Peterson was no impulse buyer. What if surgery didn't work? "What a horrible scenario," he recalls thinking. A colleague told him about Seckendorf, who prescribed painkilling shots and physical therapy - a plan Peterson's surgeon had neglected to mention. Peterson tried it and was thrilled with the results. He calls Seckendorf his "principal advisor" when it comes to his back - an endorsement that's sure to bring more well-heeled clients through Seckendorf's door. Chiropractors like Seckendorf are entirely respectable these days. Norman Marcus, however, is not. When he was asked to speak about back pain to orthopedic surgeons at Lenox Hill Hospital, where he started a pain treatment center in 1983, he didn't expect a warm welcome. Marcus was not an orthopedist or a neurologist - his training was largely in psychiatry. "It was hard to imagine that someone with my background would have the answer," he recalls. At the lectern, Marcus said that the reason back pain remained so intractable was the medical community's failure to look at anything outside the vertebrae, disks, and nerves as the cause of pain. "We need a more comprehensive approach," he recalls saying. "Surgery isn't a good idea." Some surgeons shouted him down, while others walked out. Although Marcus remained at Lenox Hill until 1997, he was persona non grata. But by then he had received his true calling from a doctor named Hans Kraus, who gained notoriety as both a daring rock climber and as President Kennedy's back guru. Kraus, then 85, and Marcus met in Manhattan in 1991. Over lunch, Kraus asked Marcus what he did for a living. "I manage pain," Marcus said. "Why don't you get rid of it?" Kraus asked. For the next five years Kraus taught Marcus his approach, which posits that muscles are the source of chronic pain. Kraus used his hands to probe for trigger points - muscles that were seizing up, say, due to injury--and then plunged a long needle deep into those spots to break them up. (This is followed by physical therapy.) Unlike acupuncture, which uses small needles to balance the body's "energy pathways," Kraus's treatment is more direct. "It's how a porcupine is different from a peach," Marcus says. But like acupuncture, Kraus's approach, championed by Marcus since Kraus's death in 1996, has never been accepted by the medical establishment. (One well-known surgeon calls it "magic.") Marcus thinks he knows why: "There's no money in it," he says conspiratorially over dinner at a local trattoria. Back surgery is big business: The market for implants and devices used in back surgeries grew 22% last year, to over $4.2 billion, according to Spinemarket and Orthopedic Network News. While a spinal fusion (basically bolting two vertebrae together) can cost upwards of $40,000, a session with Marcus runs $420. And in Marcus's tranquil Midtown office "there's no hardware, nothing to sell," he says. Yet. Marcus is developing a hand-held battery-powered device that will more accurately identify trigger points. If it works, Marcus will get a stake in a company that will market the device to physicians. Marcus won't be in attendance when James Weinstein releases his SPORT data in Seattle later this month, but he'll be watching closely. Data that support nonsurgical treatment, after all, could bring more patients his way. A few blocks uptown, Seckendorf would welcome such findings as well. And Guyer? All he'll say is that SPORT is sure "to answer some questions." But as those answers, whatever they are, trickle in, the battle for your back will continue to rage. Reporter associate Joan L. Levinstein contributed to this article. From the September 4, 2006 issue

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||