|

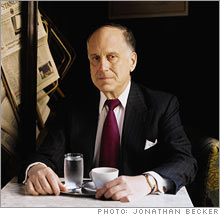

'This is our Mona Lisa' Ronald Lauder's acquisition of Klimt's 'Adele' was the most expensive known purchase of a single work of art. Can it propel his museum to greatness?

(Fortune Magazine) -- At about midnight last July 5, the New York Police Department closed Manhattan's East 86th Street. Billionaire Ronald S. Lauder walked back and forth in the street, waiting. Employees of his boutique museum for German and Austrian modern art, the Neue Galerie, waited too. They were expecting a specially appointed 18-wheeler, arriving from Los Angeles after a three-day, three-night trip. Operational details were precise: The rig stopped only for fuel, and it regularly radioed its location. Just before midnight it called from New Jersey, then from the George Washington Bridge, and then from Harlem.

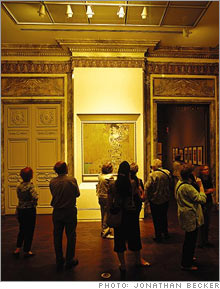

The military-like operation was designed to protect the rig's cargo, "Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I" by turn-of-the-century Austrian artist Gustav Klimt. Lauder had just purchased it for the Neue Galerie, a museum he co-founded with his late friend Serge Sabarsky. The painting reportedly cost Lauder $135 million, probably the greatest sum ever spent for a work of art. When the truck arrived, Lauder took a deep breath. "I realized that the picture was here," he says in the caf� of his museum. "This is our 'Mona Lisa.'" The painting's crate was unbolted from the sides of the truck and whisked upstairs, and "Adele" was installed behind bulletproof glass. Lauder is right to be proud. "Adele" is a first-rate work of art, one of the most famous portraits of the 20th century. It shows one of fin-de-si�cle Austria's wealthiest women, the wife of banker and sugar baron Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer. She rests against a dazzling haze of gold, wearing a silver choker and dressed in a golden gown ornamented with byzantine motifs and swirling designs. The painting would attract plenty of attention just for all that precious metal, but there's more. Klimt's rendering of Adele's full red lips and distant, heavy-lidded, sexed-up look have generated 100 years' worth of whispers. "Klimt started this painting in 1903 and finished in 1907," says Renee Price, the Neue Galerie's director. "What were they doing? It makes it kind of ..." Price looks at the floor, then back at me. "It makes it kind of spicy." The Klimt purchase was coup Lauder and the Neue Galerie hope so. For Lauder, the purchase of "Adele" marks the apex and nexus of his business, philanthropic, and public careers: His wealth, an estimated $2 billion, comes mostly from his stake in cosmetics giant Est�e Lauder (Charts), of which he was once chairman (his brother, Leonard, holds that title now, having served for many years as CEO). His philanthropic background includes not just founding the Neue Galerie but also a decade as chairman of New York City's Museum of Modern Art, and decades of leadership in charities that focus on Jewish life and post-Nazi restitution issues. Twenty years ago he represented the U.S. as its ambassador to Austria. (And as the closing of 86th Street demonstrated, Lauder is well connected in New York politics: In 1989 he ran for mayor of New York City, and he remains a prominent Republican donor.) With the purchase of "Adele," Lauder's lives came together. And he knew it. "I want to be buried right here," he says, gesturing to the fireplace in the caf� of his museum. The "Adele" purchase is more than a coup for Lauder. It is hands down the biggest American museum purchase of the past 100 years, on a par with the Metropolitan Museum's $5.5 million purchase of a Diego Vel�zquez portrait in 1971 (that would be $26 million today) or Henry E. Huntington's $729,000 purchase of Thomas Gainsborough's "The Blue Boy" for his Huntington Library in 1921 ($6.7 million today). With "Adele," Lauder and the Neue Galerie are making a grand gamble: Can a splashy, nearly unimaginable art acquisition turn an obscure museum into a must-see destination? Can a single painting - even a $135 million one - lift a museum to prominence? Throughout the late summer, other museums - and especially their wealthy donors - have been considering this same question. Four other Klimts from the Bloch-Bauer family collection are on the market and are expected to sell for a total of $100 million to $150 million. With those sales likely to come in the next month or two, the art world is buzzing about how Lauder scored his masterpiece, a story told here for the first time. In recent years museums have pursued a different strategy for raising their profiles: Hiring star architects and asking them for splashily distinctive new buildings. While many donors and trustees are motivated by a passion for art, in many cities art museums are the most desirable charitable boards on which to sit. When museums choose to build, their trustees don't just want to serve art programs but to increase the prominence and profile of their city. Business and art enthusiasts benefit from the relationship in many ways. When Minneapolis's Walker Art Center opened a $70 million expansion designed by Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron last year, the museum and its new building earned the city unprecedented international press attention. The Minneapolis business community anticipated it: Target (Charts), General Mills (Charts), Medtronic (Charts), U.S. Bancorp (Charts), Cargill, and Best Buy (Charts) (either directly or through their foundations) each gave more than $1 million, and the leaders of other Minnesota-based businesses, such as Coldwell Banker Burnet's Ralph Burnet, UnitedHealth Group CEO Bill McGuire, former Valspar CEO C. Angus Wurtele, and others, gave millions more. "I think every CEO here would tell you that one of the reasons they support the cultural institutions in this community is that it helps them attract bright employees," Walker director Kathy Halbreich says. "The wind could sweep through here pretty fast if there weren't extensive facilities to harbor people, to let them enjoy those months that we can't enjoy the outdoors." And a high-profile new cultural facility can market a city to outsiders more effectively than just about anything else. "People are profoundly pleased when they're sitting in some caf� in Paris and someone overhears that they're from Minnesota and says to them, 'The only thing I know about Minnesota is the Walker Art Center,'" Halbreich says. "And that's happened." One painting or one building would not have such an impact on New York City, but trustees at other museums will be paying attention to the impact the Klimt has on the Neue Galerie. In many ways it is a perfect test case. Even Lauder describes the pre-"Adele" Neue Galerie as a "cult kind of thing." Only about 350 people visited the museum each day, one-fortieth the attendance of the nearby Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Neue Galerie isn't listed in the Michelin Green Guide to New York City, while the Met receives 13 pages. The Neue Galerie's Austrian restaurant, Caf� Sabarsky, is better known than the museum that surrounds it. ("Perfect period piece," Zagat says. "Interminable waits.") So far, the Klimt bet is paying off. Since "Adele" has been on view, the Neue Galerie's attendance has nearly sextupled, to around 10,000 visitors a week. In each of the past three weeks the museum has set at least one single-day attendance record. "If you have a relatively small collection and you acquire a big painting that has been in the public's attention recently for reasons in addition to its beauty and quality, it's likely to make a big difference," says the director of the Art Institute of Chicago, James Cuno. "Adele" is just such a painting. It is a great work of art, to be sure, but it is also one with a remarkable history - and not just because of all those years it took Klimt to paint it. Lauder's fascination with "Adele" goes back to when he visited Austria as a teenager. On his first morning in Vienna he walked over to the Belvedere, the 18th-century palace that houses the Austrian Gallery. "When it opened, I was the first one in," Lauder says. "I'd seen 'Adele' in pictures and I'd read about it before, but nothing prepared me for how it looked. It was the first thing that I really saw in Vienna. And it was something that symbolizes so many things to me. It was just me, traveling without my parents. It symbolizes that moment of my growing up." It was the first of 40 years of encounters Lauder would have with "Adele." When the painting was completed 100 years ago, Vienna, along with Paris, was the cultural capital of the world. As was the custom among the Viennese elite, Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer wanted to celebrate his (much younger) bride, Adele, by commissioning a portrait. Ferdinand hired an artist who had spent the past decade setting Vienna abuzz with his sexually outr� takes on classical themes: Gustav Klimt. There were details about Adele Bloch-Bauer and the artist that Ferdinand may not have known: His wife had almost certainly modeled for Klimt since at least 1899, and the two had probably been carrying on an affair. Adele sat for hundreds of drawings in the years before Klimt finished his portrait in 1907. Nazi expropriation If Ferdinand knew, apparently he didn't mind: Adele's portrait immediately became the most prized object in his art collection. Sadly, Adele died in 1925. Then, in 1938, the Nazis annexed Austria. Ferdinand, one of Austria's most prominent Jews, fled to Switzerland, leaving behind palatial estates and his art collection. Nearly all of it was stolen by the Nazis, whose Moravian and Bohemian governor, Reinhard Heydrich, even took Ferdinand's grandest home outside Prague for a residence. (Heydrich, one of the key planners of the Holocaust, also gave some of Ferdinand's art collection to Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels. The SS stole the family's jewels and gave them to Hermann Göring.) The portrait of Adele ended up at the Austrian Gallery, which still "owned" it when Ferdinand died in 1945. Ferdinand's will specified that the paintings, presuming they were recovered from the Nazis or the Austrian state, go to his and Adele's niece Maria Altmann and two of her siblings. But during the decade after the war, Austria found reasons to deny the heirs' claims on six Klimt paintings and on Ferdinand's other property. (The Austrian state railway office, for example, was housed in one of Ferdinand's palaces until just a few months ago, when his heirs recovered the building. During the war it was the depot from which the Germans sent Austria's Jews to death camps.) Austria's strangest reason for not returning "Adele" and five other paintings was this: It claimed that Adele herself wanted the paintings to be given to Austria upon Ferdinand's death. In the late 1990s, however, when Austria began to open Nazi-era records to scholars and other interested parties, a journalist named Hubertus Czernin learned otherwise. He was among the first to gain access to the Bloch-Bauer records, and he found that neither Ferdinand nor Adele had specified that any Klimts go to the Austrian state. More shocking: The "donation" record that consigned "Adele" to the Austrian Gallery was dated 1941 and was signed "Heil Hitler." Altmann, who during the war had fled to Los Angeles along with her husband, Fritz (whom the Nazis briefly imprisoned at Dachau before allowing him to be ransomed), saw that the family had a chance to reclaim the paintings. Earlier this year nearly a decade of legal maneuvering paid off, and Austria returned five of the six paintings. The family decided to sell them. Enter Ronald Lauder-again. The collector had enjoyed a brief encounter with "Adele" in 1986, when he was ambassador to Austria and helped arrange a loan of the painting to the Museum of Modern Art. Now he saw the opportunity to buy it. "It wasn't until the paintings left Austria that I believed I might have a chance," Lauder says. He called MoMA director Glenn Lowry and asked him if he thought Lauder should buy it - not for MoMA, but for the Neue Galerie. Lowry flew to Los Angeles, saw "Adele," and reported back, yes. It was a shrewd move: Intentionally or not, it eliminated a potential competitor by making it clear that Lauder, MoMA's biggest art donor, wanted this one for the Neue Galerie. "It clearly was a picture destined to be at the Neue Galerie," Lowry says. Lauder called Steve Thomas, an attorney at Irell & Manella, whom the Bloch-Bauer heirs had retained to handle the sale of the Klimts. In early April, shortly after the Klimts went on temporary exhibit at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Lauder flew to L.A. for a 7 A.M. breakfast with Thomas. The art of the deal Lauder got right to the point: "If it's ever possible, I would like to consider getting 'Adele Bloch-Bauer' for the Neue Galerie," he told the attorney. Thomas said that the heirs might be interested. Lauder made an offer. "The price," Thomas recalls with a distinct pause, "was not close." Lauder asked him to express his interest directly to the heirs, Thomas agreed, and Lauder returned to New York. Lauder wasn't the only interested party. Eli Broad, a billionaire philanthropist, an art collector, and the founder of both SunAmerica and KB Home, was spearheading a bid by the Los Angeles County Museum for all five Klimts. He organized LACMA donors to make a $150 million bid for the paintings. As word of the bid traveled through the museum world, people were shocked; $150 million would have been the largest sum an American museum had ever paid for art. Still, the heirs said no. "It became clear that they were looking to get the greatest number of dollars they could," Broad says, adding that LACMA had hoped that the family would combine a sale with a partial gift - a recognition of LACMA's help in getting the paintings from Austria to Los Angeles, for insuring them, and the like. Broad's team was unwilling to go higher because the Klimts weren't LACMA's only big project: In 2005 the museum kicked off what will be at least a $182 million, Renzo Piano-designed expansion. The building project had priority. A couple of weeks after Lauder visited California, he called Thomas for an update. The attorney told him that the heirs had authorized him to have "more serious" talks. Ecstatic, Lauder suggested that Thomas fly to New York. "I have business in New York anyway," Thomas replied - as if finalizing the biggest art deal in memory wasn't the most important thing on his desk. The two men had dinner at an Austrian restaurant. Thomas was blunt: "I told Ron that if he wanted to control the painting, the terms would have to be more serious." He laid out the heirs' conditions. The family was intent on selling "Adele" to a museum, not to a private individual. The painting would have to be put on permanent display. The family would have to approve certain details of the display. "Adele" could never be deaccessioned. The painting's complicated history would have to be publicly acknowledged by the museum. The purchase price could not be made public. On and on. Finally, Thomas said that the museum to which "Adele" was sold would have to have a secure, long-term future. (Lauder says that never came up, but Thomas mentioned it to me in two separate conversations.) That condition had the potential to be thorny. The Neue Galerie is a mere toddler; its fifth birthday isn't until November. No question, the Lauder family had lavished money on the museum. Between Ronald and his mother, Est�e (who died in 2004), the Lauders had given $85 million to the Neue Galerie between its founding in 1999 and the end of 2005. Ronald Lauder has also been unusually aggressive in building its collection through purchases of top-notch German and Austrian modern art. For example, in May 2001, Lauder purchased one of the last Max Beckmann self-portraits in private hands. The $22.6 million he paid (the figure includes the auction house fee) was far beyond the auction house's $7 million to $10 million estimate, and it was a record for any German painting sold at auction. But despite such high-profile purchases, the art world still whispered about the Neue Galerie's future for a simple reason: The museum had no major financial donors whose last name wasn't Lauder. The art world thought that Ronald Lauder might get tired of bankrolling his own museum. Several museum directors I talked to for this story asked me if I thought that Lauder would "still" fold Neue Galerie into the Museum of Modern Art. "Neue Galerie will be very well endowed," Lauder says. "All the steps are being taken to make sure that the endowment is enough for 200 years. And that's about all you can do." So while the art world buzzed about the Neue Galerie's future, both sides say it quickly became a nonissue for the heirs. Lauder asked Thomas if he could mull over the terms to see if he could make it work. Thomas said that would be fine. A few days later Lauder phoned Thomas and made the deal. Lauder's bet on his museum's future was in place. Now the question was: What impact would "Adele" have on his museum? Not every expensive painting becomes an attraction. In 2004 the Metropolitan reportedly paid nearly $50 million for a nine- by six-inch painting by early Renaissance master Duccio di Buoninsegna. The painting is more important art historically than it is eye-pleasing, and the gallery in which the painting was installed is usually empty. Perhaps for that reason, in museum circles people still buzz about the Duccio's price more than about the work itself. (Met director Philippe de Montebello knows it - he phoned Renee Price just after the "Adele" purchase and said, "Thanks for making my Duccio look so reasonable.") And that's why trustees and donors have preferred buildings: immediate gratification, publicity, and civic reward. In Minneapolis the Walker's expansion paid off with 1,100 news stories. An acquisition doesn't usually have that kind of quick influence, but over time the impact can be greater. "If I had total druthers and could buy a painting for a painting vs. spending it on a building, I might be tempted to say that painting is going to last forever and will always be a draw," says Harry Parker, the recently retired director of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. An example of the long-term benefit of an iconic artwork such as "Adele" can be found at the Art Institute of Chicago, home to three of the most famous paintings in America: Georges Seurat's composition of colorful dots, "Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte" (acquired in 1926); Grant Wood's portrait of farmer, wife, and pitchfork titled "American Gothic" (in 1930); and Edward Hopper's fluorescent-lit diner, "Nighthawks" (in 1942). Generations of Chicagoans have grown up with the three paintings and consider Chicago's stewardship of them a point of civic pride. And because each image is in the public domain - anyone from an ad firm to a television producer to a T-shirt designer can use the images without paying for them or needing contractual permission - the paintings automatically market themselves, the museum, and Chicago. Lauder understands this - when he refers to "Adele" as the Neue Galerie's "Mona Lisa," he's not just referring to the quality of the work of art. The Neue Galerie already intends to make "Adele"-related items available in its design store. It plans a couple of publications that people will be able to buy in its store and perhaps elsewhere. But beyond that, there's not much the Neue can do. "Adele" is in the public domain too. It is an unusual asset in that how it will impact the Neue Galerie in the long run is up to other people. What the Chicago examples have in common is that they were acquired about 70 years ago, before America's great museums were good. In other words, the Art Institute acquired them at a point in its development that mimics where the Neue Galerie is now. Now that Lauder has Adele, he's thinking about what's next. He may make a bid for one or more of the other four Klimts that the Bloch-Bauer heirs are selling. And he may just build a new museum-say, a Neue Galerie Vienna. "I think that would be a lot of fun," he says, trailing off. "But at this point we have our hands full here." Substance amid the spotlights at the Clinton Global Initiative. |

|