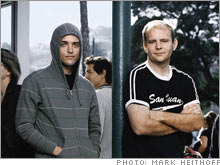

The race to create a 'smart' GoogleEverything you buy online says a little bit about you. And if all those bits get put into one big trove of data about you and your tastes? Marketer's heaven. Fortune's Jeffrey O'Brien reports.The setup (Fortune Magazine) -- "If a girl says she likes 'The Big Lebowski,' instantly, I think 'stoner.' " That's Matthew Kuhlke speaking. We're sitting at a table full of grilled meat and jug sodas on a late-summer weeknight in midtown Atlanta. "She hangs out with a bunch of guys. She dates them a little bit, but she really just likes the attention." Also at the table: Kuhlke's business partner, Adam Geitgey. Kuhlke and Geitgey grew up in nearby Augusta and finish each other's thoughts the way lifelong friends often do. The pair of unattached, hormonal twentysomethings also have a knack for turning conversations toward dating. "If all a girl likes are romantic comedies," Geitgey adds, "I'd be worried that she's going to be co-dependent, emotionally needy."

I've invited Kuhlke and Geitgey to the restaurant of their choosing to talk about movies and personality. They opted for the Vortex, a bar and grill with a skull for a logo and a rash of thrift-store salvage covering every last bit of wall space. Chairs dangle from the ceiling; a skeleton sits atop a motorcycle near an aluminum camel. As the wait staff buzzes around in hipster flair - piercings, tattoos, dog collars - the former Georgia Tech roommates explain the underlying premise of their company, What to Rent. The site administers a personality test to visitors and recommends DVDs based on the findings. To demonstrate the connection between movies and personality, the budding entrepreneurs have been describing prototypical fans of everything from "Raging Bull" to "Finding Nemo." Now they'll attempt something more difficult: They'll each pick someone in the restaurant and, without ever talking to them, divine their single favorite movie. Once they make their picks, my plan is to corner the unsuspecting strangers and see how perceptive these film nerds really are. Recommender systems like Whattorent.com are sprouting on the Web like mushrooms after a hard rain. Dozens of companies have unveiled recommenders recently to introduce consumers to Web sites, TV shows, other people - whatever they can think of. The idea isn't new, of course. In a time of impersonal big-box stores and self-checkout stations, independent shopkeepers compete by doing this sort of thing every day. What does the fact that you drive a Prius and buy organic baby food say about you? At the farmer's market, it says, "Grass-fed ribeye, heirloom tomatoes and line-caught salmon." In the local appliance store, you're looking for a low-energy, front-loading washer with matching dryer. For those shopkeepers, it's more than a parlor trick. It's good business. We don't just buy products, we bond with them. We have relationships with our things. DVD collections, iTunes playlists, cars, cell phones: Each is an extension of who we are (or want to be). We put ourselves on display through our purchases, wearing our personalities on our sleeves, literally and figuratively, for the world to see. And if you don't subscribe to this sort of materialism - if you don't define yourself by the clothes on your back or the neighborhood you live in - well, that's just another brand of expression. In the real world, we use apparent information, coupled with context, experience and stereotypes, to size each other up. This sort of intuition is useful and often accurate, but it's also fallible. Online, the picture becomes clearer. Consumers now routinely rank experiences on the Web - four stars on IMDb for "The Departed," three stars on Epinions for a Roomba vacuum, a positive eBay rating, a Flickr tag. Each time you leave such a mark, you help the rest of us make sense of all the look-alike, sound-alike stuff on the Web. You also leave a trail. For the company that can decipher all that information, the opportunity is staggering. That company will know you better than the shopkeeper knows you, better than the credit bureau or, arguably, even your spouse. It will pinpoint your tastes and determine the likelihood that you'll buy any given product. In effect, it will have constructed the algorithm that is you. New kids in town There's a sense among the players in the recommendation business - from newcomers like MyStrands and StumbleUpon to titans like Yahoo (Charts) and Sun (Charts) - that now is the time to perfect such an algorithm. The Web, they say, is leaving the era of search and entering one of discovery. What's the difference? Search is what you do when you're looking for something. Discovery is when something wonderful that you didn't know existed, or didn't know how to ask for, finds you. When it comes to search, there's a clear winner - a $145 billion company called Google (Charts). But there is no go-to discovery engine - yet. Building a personalized discovery mechanism will mean tapping into all the manners of expression, categorization, and opinions that exist on the Web today. It's no easy feat, but if a company can pull it off and make the formula portable so it works on your mobile phone - well, such a tool could change not just marketing, but all of commerce. "The effect of recommender systems will be one of the most important changes in the next decade," says University of Minnesota computer science professor John Riedl, who built one of the first recommendation engines in the mid-1990s. "The social web is going to be driven by these systems." Amazon (Charts) realized early on how powerful a recommender system could be and to this day remains the prime example. The company uses a series of collaborative filtering algorithms to compare your purchasing patterns with everyone else's and thus narrow a vast inventory to just the stuff it predicts you'll buy. "Personalized recommendations," says Brent Smith, Amazon's director of personalization, "are at the heart of why online shopping offers so much promise." So far, the company has struggled to deliver on that promise. Its system favors popular, obvious items and tends to come off less like a trusted shopkeeper than a pushy salesman: If you liked the novel "The Corrections," you'll see suggestions to buy "The Discomfort Zone" and everything else Jonathan Franzen has written. If you bought a gift for a baby shower, you're bound to get a stream of recommendations for cheap plastic toys and birthing blankets. The new generation of recommenders will do better. Some employ filters that factor in more variables. Others analyze the contents of what they're recommending to grasp why you like something. A third category, hybrid recommenders, combines both strategies. To tap into some of the brainpower gathering in the recommender space, Netflix (Charts) recently established the Netflix Prize, offering a $1 million bounty to anyone who can improve by 10 percent the efficacy of the company's recommender system. A few days before the contest was officially announced, VP of recommendation systems Jim Bennett expressed doubt about whether anyone would reach the goal ahead of the ten-year deadline, but said it'd be well worth the $1 million if someone did. Five weeks later, 37 registrants had already posted improvements to the Netflix system. Two contestants were just short of halfway to the goal. The magician's secrets Back at the Vortex, Kuhlke and Geitgey discuss how their parlor trick works. They'll draw on their knowledge of cinema and their experience categorizing hundreds of films - by star power, plot complexity, etc. - at What to Rent. "When you watch a movie, you interact with it like you're interacting with another person," Kuhlke says. "You're forming a relationship." Geitgey goes first. He scans the crowd and homes in on a target, a guy delivering meals and clearing dishes. On their site, Kuhlke and Geitgey use a series of odd questions to determine a user's personality. "How much money would it take for you to wear a neon-green fanny pack for the rest of your life?" Or: "What do you like better, reading a book or watching TV?" Here, it's all about observation. This is what Geitgey sees: tattered jeans, a steel bracelet, a few tattoos. The target may be gathering dishes but seems too authoritative to be a busboy. He appears to be in his late 20s and is working, Geitgey surmises, "in a youth-trendy restaurant in the part of the city where people that age who don't have real jobs hang out." Geitgey makes a few leaps. "Those are the kind of guys who barely made it through high school because they couldn't focus, but spend most of their time reading light philosophy books by singers-turned-writers like Nick Cave," he says, insisting that the target is trying to square budding intellectualism with his physical image. So. Which movie? "He would be interested in things that have an underlying philosophy but are also physically intense," Geitgey concludes. " 'Starship Troopers' fits that exactly - a bit of mild antiestablishment philosophy with some bad-ass bug-killing." Musical taste In a few short years, Pandora has become the most efficient new-music discovery mechanism in history. That's not saying much, really. Consider the alternatives: scouring magazines for reviews, flipping through albums in the record store, listening to radio stations all play the same songs. At Pandora.com, you type in the name of a band or song and immediately begin hearing similar tunes that the site's recommender system - a.k.a. the Music Genome Project - has determined you'll enjoy. By rating songs and artists, you can refine the suggestions, allowing Pandora to create a truly personalized station. Unlike collaborative filtering engines, Pandora understands each song in its database. Forty-five analysts, many with music degrees, rank 15,000 songs a month on 400 characteristics to gain a detailed grasp of each. A former musician and film composer, founder Tim Westergren came up with the idea for Pandora while scoring movies for directors. "They weren't musicians, so no one was saying, 'I like minor harmonies and woodwinds,' " he says, leaning back in his chair at Pandora's Oakland headquarters. "So it was my job to figure out their musical taste. I developed a genome in my head, and would say, 'Okay, you like this song; do you like this one?' " Four million people now use Pandora the same way those directors used Westergren. Let's say I type in Bloc Party, a pop/punk band that's part Franz Ferdinand, part Sonic Youth. The next tune I hear might be from We Are Scientists, a Brooklyn indie band with, Pandora determines, similar "electric-rock instrumentation, subtle use of vocal harmony, and minor-key tonality." Next I get a catchy song from a pop-punk/emo band called Fire When Ready, which stands at No. 225,301 on Amazon's music sales list. It's safe to say that few consumers are searching for this band. But on Pandora, it's only a few degrees of separation from Bloc Party. To draw a line from Bloc Party to Fire When Ready, the Music Genome Project combs through hundreds of thousands of songs and millions of pieces of user feedback. It's an impressive technological accomplishment but not nearly as impressive as the implications. If Pandora can nail me as a fan of a band that few people have ever heard of, and my musical tastes are an intimate expression of who I am, then Pandora could introduce me to a lot more than music. Take it from Jason Rentfrow. "If you know I like Ahmad Jamal," Rentfrow says, referring to the 64-year-old jazz musician who played piano for Miles Davis, "that'll stimulate other information that you can infer about me." So Rentfrow likes sophisticated jazz. What sort of picture does that paint? If you think he's intelligent, articulate, a bit geeky and soft-spoken and wears glasses, well, you'd be relying on stereotypes. And you'd be right. Of course no person is one-dimensional. Rentfrow also likes the rap group A Tribe Called Quest. With that information, you would probably redraw his caricature. Now maybe he seems younger and more open-minded. Revealing a list of his 50 favorite artists would flesh him out even more. Rentfrow is a 30-year-old psychology professor at the University of Cambridge (Britain). To study the links between musical taste and personality, he and University of Texas psychology professor Sam Gosling administered personality tests to 74 students and instructed each to submit a list of ten favorite songs, which were then played for another set of volunteers. After listening to the songs, the second group ranked each person on 28 characteristics. Rentfrow then compared those results with the earlier personality tests. Music turned out to be a poor predictor of emotional stability, courage and ambition, but accurate on extroversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness, imagination and even intellect. An ongoing study conducted by Rentfrow at www.outofservice.com, where 90,000 people have taken a music/personality quiz, pushes the point even further, tying taste to political leanings, demographics, lifestyle, favorite authors - movies even. As recently as a decade ago, when musical preference was the province of a stack of CDs in the living room, such research may have been a dead end. But music recommenders can now draw lines from musical tastes to all sorts of things. Rentfrow and Gosling explored the connection between music and personality out of scientific curiosity. But the connection could have broad applications in business. Goodbye, context-based advertising. Hello, personality-based advertising. Educated guesses Geitgey's made his choice: "Starship Troopers." Now it's Kuhlke's turn. He's spotted a waitress. She's in her late teens or early 20s, black hair in a bob, very cute. She looks at the floor as she walks and avoids eye contact with customers. "She's unhappy," Kuhlke surmises. "She's working around all these jerks who just want to have sex with her." Geitgey chimes in, suggesting she wasn't popular in high school and is shaking off her past by working in a cool place. Kuhlke cuts him off. "This place is the Applebee's of cool!" he insists. "If it was really cool, it wouldn't be a chain and there wouldn't be a paid parking lot across the street." So what? "So she'd pick the wrong movie," he continues. "She'd like an old-school romantic comedy, but she'd pick 'Breakfast at Tiffany's,' a totally crappy movie. She's cool enough to know she should pick Audrey Hepburn, but not cool enough to pick the right movie, 'Roman Holiday.' " The waitress is obviously attractive, maybe the prettiest woman in the restaurant. And she does seem bothered by - or at least indifferent to - her surroundings. But that hardly makes her prone to ill-informed choices. Kuhlke reconsiders. Maybe she would like 'Roman Holiday.' He clearly wants her to say 'Roman Holiday.' Flustered, he jumps off the romantic comedy train altogether. She's disaffected, he insists, throwing his arms in the air. "Girl, Interrupted." Big brother online Just back from a visit to his childhood home in Kiev, Max Levchin is in his South of Market office holding up a propaganda handbill that he picked up in Moscow. He wants to mount it on a wall at his new startup, Slide. The poster features a railroad worker staring out from a caboose and a headline that Levchin translates aloud. "Literally, it says 'Night - not a hindrance to work!' " he says, mocking a sinister laugh, "though the implication is clearly, 'Keep working, bitches!' " Levchin's team doesn't really need the reminder. The 31-year-old CEO drinks eight espressos a day and possesses a work ethic that's famous around Silicon Valley. He often arrives in the office by six and is still there 12 or even 18 hours later. After co-founding the online payment service PayPal in 1998, he battled fraudsters before taking the company public in 2002 and selling it several months later to eBay (Charts) for $1.5 billion. "The crux of PayPal is a risk-management company," he explains. "We perfected the ability to say, 'The odds of you stealing money are X.' " Levchin cross-referenced traffic patterns, auction histories, user interactions, geography and a thousand other factors to root out fraud. "I would obsess on multivariate analysis. I'd have printouts and printouts graphing the relationship between any two variables," he says. "For a long time we didn't even patent this stuff because it was so secret." These days, Levchin has the typical angst of a second-time entrepreneur. He's obsessed with proving that his first success wasn't a fluke, and he wants to exploit the biggest opportunity he can find. He's using what he learned at PayPal, not to root out fraud but to create the best recommender system he can imagine, one that will cover the entire Web, pulling content of all kinds - music, movies, gadgets, blogs, news stories, cars, one-night stands, you name it - filtering it according to individual preference and delivering it to the desktop. Instead of quantifying the odds of your stealing money, he's building a "machine that knows more about you than you know about yourself." If Slide is at all familiar, it's as a knockoff of Flickr, the photo-sharing site. Users upload photos, which are displayed on a running ticker or Slide Show, and subscribe to one another's feeds. But photos are just a way to get Slide users communicating, establishing relationships, Levchin explains. The site is beginning to introduce new content into Slide Shows. It culls news feeds from around the Web and gathers real-time information from, say, eBay auctions or Match.com profiles. It drops all of this information onto user desktops and then watches to see how they react. Suppose, for example, there's a user named YankeeDave who sees a Treo 750 scroll by in his Slide Show. He gives it a thumbs-up and forwards it to his buddy" we'll call him Smooth-P. Slide learns from this that both YankeeDave and Smooth-P have an interest in a smartphone and begins delivering competing prices. If YankeeDave buys the item, Slide displays headlines on Treo tips or photos of a leather case. If Smooth-P gives a thumbs-down, Slide gains another valuable piece of data. (Maybe Smooth-P is a BlackBerry guy.) Slide has also established a relationship between YankeeDave and Smooth-P and can begin comparing their ratings, traffic patterns, clicks and networks. Based on all that information, Slide gains an understanding of people who share a taste for Treos, TAG Heuer watches and BMWs. Next, those users might see a Dyson vacuum, a pair of Forzieri wingtips or a single woman with a six-figure income living within a ten-mile radius. In fact, that's where Levchin thinks the first real opportunity lies - hooking up users with like-minded people. "I started out with this idea of finding shoes for my girlfriend and hotties on HotorNot for me," Levchin says with a wry smile. "It's easy to shift from recommending shoes to humans." If this all sounds vaguely creepy, Levchin is careful to say he's rolling out features slowly and will only go as far as his users will allow. But he sees what many others claim to see: Most consumers seem perfectly willing to trade preference data for insight. "What's fueling this is the desire for self-expression," he says. As Levchin and his charges set out to build a new type of search engine - a new Google - one question becomes obvious: Where's the old Google? VP of engineering Udi Manber refuses to comment on whether there's a recommender system in the pipeline. But it's a safe bet something is coming. Google's director of research, Peter Norvig, is an advisor to CleverSet, a recommender company in Seattle. Steve Johnson, CEO of Boston-based recommender system ChoiceStream, which provides the collaborative filtering engine behind AOL.com, Blockbuster.com, iTunes and Directv.com, says he's been talking to Google about building a system for YouTube. "Google needs to go to a preference-based search paradigm, and I believe they're moving in this direction," Johnson says. Payoff Kuhlke and Geitgey never had Google-sized ambitions for Whattorent.com. The co-founders, who recently took day jobs as software engineers on opposite ends of the country, didn't expect their site to be a huge moneymaker. They were a couple of undergrads trying to save their pals from the movie geek's ultimate nightmare scenario - walking around Blockbuster with no idea what to rent. They accomplished that much. But they may have also helped pave the way for a whole new way for marketers to get inside your head. We've paid the bill at Vortex, and it's the moment of truth. We approach the guy with tattoos, who, as it turns out, is the restaurant manager. We tell him what we've been up to and ask him to tell us his favorite movie without thinking. "Brianna Loves Jenna," he says with half a smile and a lift of the eyebrows. Everyone laughs. New rule: no porn. Then the guy crosses his arms, pauses for a moment, and exclaims, "Starship Troopers!" High-fives all around. Geitgey nailed it. Now the waitress. We haven't seen her talk to anyone since we walked in. Kuhlke and Geitgey hang back as I approach her. For the first time all night, the woman who will be remembered as "Audrey" lifts her cheeks to reveal a smile that comes both from a set full of wonderful white teeth and a pair of impossibly green eyes. "Roman Holiday," ________________________ From the November 27, 2006 issue

|

|