By Stephanie N. Mehta, Fortune senior writer

(Fortune Magazine) -- About 20 miles south of Memphis, along the Mississippi River, Tunica County, Miss., used to be a popular stop for journalists and politicians looking to be appalled by black poverty.

In 1985, Jesse Jackson visited the town of Tunica, the county seat, and pronounced it "America's Ethiopia." Then "60 Minutes" showed up and spent some time in Sugar Ditch Alley, a neighborhood of crumbling shacks named for its open sewer.

|

| A busy night at Tunica's casinos and hotels. |

|

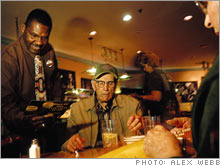

| Gambling has made opportunities for buffet manager Michael Branch. |

Henry Nickson, 31, grew up there. "When I got to college and told people I was from Tunica, the first thing they'd say was 'Sugar Ditch.'" By the time Nickson was a senior at Jackson State University, things were different: "People would say, 'Tunica? Y'all got all that money.'''

"All that money" comes from the nine Vegas-style casinos that have sprung up amid the cotton, soybean and rice fields in the northern part of Tunica County. In 1990 the state legislature legalized dockside gambling in the strapped counties along the river and Gulf Coast. While several counties rejected the idea, Tunica grabbed it.

Today aspects of Tunica still feel like the old rural South. Fields stretch out for miles and miles, and waitresses at the Blue and White restaurant downtown serve fried catfish and okra and call complete strangers "baby." But now Tunica is the fifth-largest gaming market in the U.S., behind Las Vegas, Atlantic City, Chicago and Detroit, and ahead of Reno and Connecticut's twin Indian casinos Foxwoods and Mohegan Sun.

In that north part of the county, an area formerly known as Robinsonville but now called Tunica Resorts, huge gaming parlors stand over fields where farmers grow cotton and soybeans. The casinos themselves sit on enormous barges along the river, while the hotels, like the 31-story Gold Strike, the tallest building in the state, sit on dry land. At night the glow of neon fills the sky.

Tunica looks nothing like the county Fortune visited in 1990 as part of a story on rural poverty. Back then we declared that Tunica "is unlikely to ever generate enough jobs" for its residents.

In fact, thanks to gambling, Tunica has generated plenty of jobs for its 10,000 residents, and then some. Casinos and related businesses now employ more than 15,000 people, who travel to work from three states. The gaming tables and slots alone brought in revenue of $1.2 billion last year, 4 percent, or $48 million, of which went to the county's coffers for items such as repairs to seniors' homes, a recreation center and the public-school budget.

More troubles ahead

Tunica is a powerful example of what legalized gambling can do for a poor area. The problem now is what to do next: Gambling appears to have peaked here. For roughly the past six years gaming revenue in the region has been flat. Local leaders say consolidation in the industry has prevented casino operators from making further investments that might lure new visitors. In markets such as Atlantic City and Connecticut, however, casino companies are building new properties or dramatically upgrading old ones.

Community leaders insist Tunica is on the cusp of its next stage of growth: A new connector to Interstate 69 is now open, shaving 20 minutes off the drive from Memphis. Ground was broken last September for a 900-home housing development, and a 2,000-unit project is set to begin construction this May. There's talk of a new casino coming to town, possibly as early as this year, and the county has set aside a huge parcel of land to attract new businesses, possibly a factory or plant.

But gaming industry experts say there is no precedent for Tunica's plans to reinvent itself yet again. "I can't think of a market that introduced gaming as an impetus for generating jobs that then diversified to the point that gaming became secondary," says Michael French, a partner in PriceWaterhouseCooper's hospitality and leisure practice.

Furthermore, the world has changed dramatically since Tunica first embraced casinos 15 years ago. Instead of competing with the county next door for jobs and economic opportunities, communities, even rural ones like Tunica, need to think about rivals in emerging markets such as China and India.

"Casinos don't grow skills," says Mark Minevich, an international strategic advisor. "They don't nurture talent." Minevich thinks the most successful rural areas instead will build outsourcing capabilities - call centers and help desk functions - that have been going overseas in droves.

As good as it gets

It's hard to see Tunica making that transition: Despite the big infusion of casino cash into the local economy over the past few years, the local high school is a stubborn underperformer. Affordable, good-quality housing in this land-rich county is shockingly scarce. And the poor remain: Nearly a quarter of the residents still live below the poverty line. You might say it feels as if life in Tunica is about as good as it is going to get.

Interviews with dozens of Tunica residents demonstrate that Tunica is substantially better off today than it was 15 years ago. "Before the casinos came, this was almost like a ghost town. People just didn't have hope," says Mack Williams, 51, a custodian at Sam's Town casino. "Everybody's got more hope now."

There was so little hope in the old days that no one, not even the ministers in this Bible Belt community, raised a fuss about gambling. (Not that they had the chance: The county supervisors simply authorized gaming shortly after the state legalized it.) Williams himself is an assistant minister at a local Church of Christ.