A hedge fund superstarCitadel founder Ken Griffin is already one of the world's most powerful investors. But he wants to be much more than a billionaire wunderkind with a head for figures. Fortune's Marcia Vickers takes an unauthorized look inside his world.(Fortune Magazine) -- On North Michigan Avenue in Chicago, on the Magnificent Mile, sits one of the city's tallest and swankiest residential buildings. The most notable feature of the structure, a seven-year-old art deco-ish number called the Park Tower, is a two-story penthouse with a set of enormous, darkly tinted windows that give the place a Howard Hughes-like mystique. Occasionally passersby shopping at the Armani or Tiffany stores nearby catch a glimpse of the windows and tilt their heads skyward with an "I-wonder-who-lives-there?" stare. The answer - Kenneth C. Griffin - probably wouldn't make much of an impression, which suits a secretive hedge fund manager like him just fine. In fact, he fits the hedge fund stereotype quite nicely. He's young (38), fantastically rich (worth $2 billion or so), and he collects museum-quality art (he recently spent $80 million to take a Jasper Johns off David Geffen's hands).

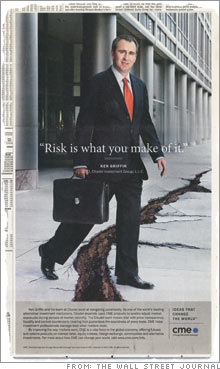

He's got the trophy home, obviously, and is married to a very attractive woman, the former Anne Dias. The company he founded and runs, Citadel Investment Group, has around $13 billion in assets and is one of the largest and most powerful funds in the world. What sets him apart from his fellow nouveau zillionaires is the scale of his ambition. Griffin, say people who know him, doesn't want a reputation merely as a hedge fund legend like Tiger Management's Julian Robertson or SAC Capital's Steve Cohen. What he really seems to want is to build an edifice for the ages: a diversified, large-scale financial institution on the order of Goldman Sachs (Charts) or Morgan Stanley (Charts). To get there Griffin has launched a flurry of business deals: buying up a mortgage operation here, some distressed assets from another hedge fund there. Last fall Citadel announced plans to sell up to $2 billion in bonds - a first for a hedge fund. All the while, there's steady speculation that Citadel will go public. (Griffin declined to be interviewed for this piece in time to meet our deadline.) The ambition doesn't stop there. Griffin seems to be going for full-blown, captain-of-industry immortality, the kind achieved by titans who didn't just dot, but shaped, the landscape of business over the past century. As a former Citadel manager put it recently, "Suddenly it seems like Ken wants to be a J.P. Morgan or John D. Rockefeller." That's hard to do if you're an adherent of the reclusive, cloak-and-dagger Way of the Hedgie. So Griffin and his society-savvy wife have been throwing themselves an extended coming-out party. He's on the Chicago 2016 Olympics organizing committee and various high-profile boards. In October he and Anne made headlines around the world when they donated $19 million to the Art Institute of Chicago - one of the largest private donations ever made to the museum. He even appeared in a Chicago Mercantile Exchange ad in The Wall Street Journal. Griffin looks a little tense in that Chicago Merc ad. That isn't surprising given his line of work, and it's even less surprising to those who know him, because he really does appear to be conflicted about publicity. "He's an introvert's introvert," says an acquaintance. "And here he is in a national newspaper ad wearing a red power tie!" Of course, Griffin will have to learn to be comfortable with his public if he wants to fulfill his grand plans. The empire builders Griffin aspires to emulate didn't just have amazing analytical powers; they were also preternaturally shrewd psychologists. They may have been rapacious robber barons, but they knew how to manage - or at least accepted the primacy of the human factor in business. Griffin, says a former trader, "believes management, like everything, is all about process, methodology." There are plenty of people like that among the 8,000 hedge funds now in existence. And those funds come in a wide variety of flavors, even in the top tier. You've got Tire Kickers - funds that closely examine the companies they invest in. The archetypal Tire Kicker fund is the defunct Tiger Management, founded by Robertson. There are the Gunslingers, like SAC Capital, which trade frenetically, seeking any edge they can get. There are the Global Sophisticates, like George Soros's Quantum Fund in its heyday and now Stanley Druckenmiller's Duquesne Capital (Charts), which make big bets on interest rates and currencies. And you've got your Quants, which rely heavily on computer technology to invest; they are often run by mathematicians and physicists and whatnot. Citadel is basically a quant fund. Its trading programs furiously buy and sell on behalf of the firm's two main funds, Kensington Global and Wellington. (Citadel accounts for more than 3 percent of average daily trading volume on the New York, Tokyo and London exchanges, 15 percent of the options market, and as much as 10 percent of the Treasury bond market.) "We're a tech firm first and foremost that happens to trade," Citadel's longtime CIO, Tom Miglis, likes to say. Technology reaches into every line of Citadel's business, even as Griffin adds new ones. Citadel is the only hedge fund with a market-making options business and is one of the first to have its own stock loan and borrowing capabilities. It also has an elaborate back office, the boring innards of financial firms where transactions are processed, orders fulfilled and so forth. The 363-page private bond prospectus that was somehow leaked to the press revealed that Citadel plans to sell its back-office expertise to other funds, yet another step away from plain-vanilla hedgieville. It even has a duplicate computer system in an undisclosed location outside Chicago - standard for big banks, but highly unusual for a hedge fund. "There's a risk-management paranoia there," says a former top executive. "It's like the North American Ballistic Military Command." The point of all this technology is to make the firm more agile. It allows Griffin "to assess and grasp situations and get his team deployed at lightning speed in almost any situation," says a former trader. "No other hedge fund has this." "Ken is a brilliant innovator," says Alec Litowitz, a longtime star Citadel trader who left to start his own fund, Magnetar Capital. "He has transformed what it means to be a hedge fund." Investor returns Those who invest with Citadel don't do it because of Griffin's tech cred. They do it for the returns: Kensington, Citadel's largest fund, delivered average annual gains of around 22 percent over the past nine years. That's after fees, and as you might guess from Citadel's stellar performance, those fees run pretty high. Most hedge funds follow the "2 and 20" rule - a 2 percent annual management fee and a 20 percent annual performance fee (i.e., they keep a fifth of the profits). Citadel's investors are willing to pay the customary 20 percent cut of the profits, but cough up an unusually high management fee - it was 8.75 percent in 2005. An excellent example of Citadel investors getting what they pay for happened last fall. On the morning of Sept. 18, Griffin feverishly exchanged phone calls with Amaranth Advisors, the $9.5 billion hedge fund. Amaranth had made one of the most disastrous trading bets ever, wagering that natural gas prices would rise. Instead, prices had plummeted, and Amaranth had lost $4.6 billion, almost half its assets, in one week. (Amaranth would eventually lose a total of $6.4 billion.) Griffin remained characteristically calm as he helped negotiate the purchase of the pulverized portfolio, say people close to the situation. Working with his energy team - some handpicked from the remains of Enron - he calculated the risks, analyzing the positions and the market. At times he was talking intensely with Charlie Winkler, Amaranth's chief operating officer, who had joined Amaranth from Citadel five years earlier. Winkler knew it was the kind of deathwatch deal Griffin relished. Then, "while the corpse was still warm," as one observer put it, Griffin bought half of Amaranth, while J.P. Morgan Chase took the rest. Some on Wall Street thought it was a foolish bet, joking that Griffin had "Amaranthed" himself. Natural gas prices, after all, could have continued to plummet. But they didn't, and Griffin, as usual, ended up in the money. Amaranth paid Citadel an unspecified cash fee - probably about $1.5 billion, a source says - for taking on the troubled portfolio. In September, Citadel posted a 3 percent gain on its energy investments, according to a fund document; that helped spur the fund to one of its most spectacular years ever. In 2006, while the average hedge fund gained 13 percent, Citadel was up 30 percent, according to investors. For the past year or so, Citadel has been investing in China and making big bets on credit derivatives. "Ken is great at recognizing patterns without relying on lots of analysis," says Mark Yusko of Morgan Creek Asset Management, a Citadel investor. "He can synthesize loads of information faster than anyone." You hear that kind of comment a lot about Griffin. He doesn't look at all like some mathaholic - he's about six feet tall and has short salt-and-pepper hair, perfectly pleasant-looking. But he seems most comfortable in black-box mode: distilling complex securities models or whatever market voodoo is on his mind. With an unnerving, unblinking blue-eyed stare, he grills underlings - many of them math and physics Ph.D.s from MIT or Harvard, his alma mater - about things ranging from the risk premium to neural stochastic dynamics (don't ask). "Ken only wants to have what he calls 'high bandwidth' conversations," says a former trader. "He might zone out if you try to talk with him about your family, for example. He's not the kind of guy you can have a beer with." |

Sponsors

|