(Fortune Magazine) -- At dawn, under the belly of a wrought-iron bridge, 12-year-old Somnath Dantoso drops a dumbbell-shaped magnet from his makeshift raft into New Delhi's Yamuna River. It is a routine he has followed daily for four years. The magnet sinks 30 feet below the river's inky surface and on a good day brings up about 50 rupees' ($1.22) worth of coins that commuters toss in for good luck. "When people stop throwing coins, I'm going to open a grocery shop," he says. "Otherwise I'll do this the rest of my life."

The coins are the least of the Yamuna's problems: The stretch of river where Somnath works is so contaminated that it can hardly sustain marine life. Garbage cascades down its banks, giving off a fetid stench. And half of the city's raw sewage flows into its waters. "The river is dead," says Sunita Narain, director of the Centre for Science and Environment, a watchdog group in New Delhi. "It just has not been officially cremated."

|

| Unsafe for swimming: A bather emerges from the polluted Yamuna in New Delhi. |

|

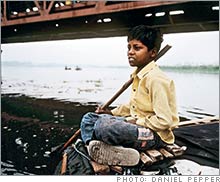

| Fishing for rupees: Twelve-year-old Somnath

Dantoso on the Yamuna |

The blighting of the Yamuna is a symptom of India's unchecked urban growth and poor oversight. The government has spent nearly $500 million trying to clean up the river, most of it going to waste-treatment stations, yet pollution levels more than doubled from 1993 to 2005. And they continue to rise.

The problem is that 11 of the city's 17 sewage-treatment plants are underutilized; a quarter of them run at less than 30 percent capacity. That's because the city's sewer system is so corroded and clogged it can't deliver to the treatment plants the waste of the 55 percent of New Delhi's 15 million inhabitants who are connected to the sewage system.

And even if the plants were fully utilized, there would still be the waste from 1,500 unplanned neighborhoods, where sewage "finds its way into the drains and the river," says Arun Mathur, head of the Delhi Jal Board, the government agency responsible for the city's water supply.

The Centre for Science and Environment says that nearly 80 percent of the river's pollution is the result of raw sewage. Combined with industrial runoff, that comes to more than three billion liters of waste per day, a quantity well beyond the river's assimilative capacity. The frothy mix is so glaring it can be viewed on Google Earth.

The Yamuna, which flows 855 miles from the Himalayas into the Ganges, isn't India's only polluted river. Eighty percent of the country's urban waste goes directly into rivers, many of which are so polluted they exceed permissible levels for safe bathing.

The costs to the economy are enormous. Waterborne diseases are India's leading cause of childhood mortality. Shreekant Gupta, a professor at the Delhi School of Economics who specializes in the environment, estimates that lost productivity from death and disease resulting from river pollution and other environmental damage is equivalent to about 4 percent of gross domestic product. "Some of this feeling of euphoria," he says of India's 9 percent growth rate, "gets a bit dampened thinking of environmental degradation."

Sheila Dikshit, New Delhi's chief minister, says the government simply followed the recommendations of outside consultants who encouraged the building of expensive sewage-treatment plants but didn't anticipate the surge in migration of rural poor to New Delhi. "We're tired and frustrated from spending money," she says.

But not everything can be blamed on consultants. An obfuscating web of political appointees, civil servants and weak elected officials has made accountability almost impossible. At least eight city, state and federal agencies oversee various aspects of the Yamuna's cleanup, alternately competing for funds and sometimes passing the buck when public anger reaches a boiling point.

The problem isn't insurmountable, says Gupta, the economics professor. He argues that a clean river is a public good for which people should have to pay. But New Delhi's citizens aren't charged sufficiently for the millions of gallons of waste they flush daily. "Our municipal finances are in a mess," he says, "because we essentially don't raise money from property taxes and user charges, the two sustainable sources of revenue."

Most New Delhi politicians don't want to risk levying new taxes and upsetting voters who already face regular brownouts and water shortages. Some politicians also look favorably on lucrative infrastructure appropriations, which can result in backing from businessmen who receive the contracts.

The fate of the Yamuna is now in the hands of India's Supreme Court, which took up the issue on its own in 1994 after press reports highlighting the river's dismal condition. In early May the Court approved a proposal from the Delhi Jal Board to build interceptor sewers that would channel the waste flowing from unconnected parts of the city to the sewage-treatment plants.

The pricetag for the new construction: another $500 million. Mathur, the board's CEO, predicts that by 2010 - just in time for New Delhi to host the Commonwealth Games set to take place along the banks of the river - the Yamuna will experience a 90 percent improvement in water quality.

But Narain, the director of the Science and Environment Centre, says that throwing more money into a sewage-diversion infrastructure project would be a waste. She has called for rethinking the city's pollution-control paradigm and building small-scale waste-treatment plants on a neighborhood basis, reusing the water locally, and charging higher rates for excessive wastewater.

India's Prime Minister, Manmohan Singh, has also come down on the side of innovation. In a speech delivered on World Water Day in March, he called on India's scientists, technologists and engineers to redesign the flush toilet.

In the meantime, Somnath Dantoso will continue to collect his 50 rupees a day.