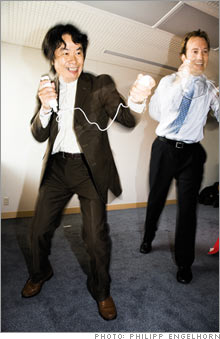

Wii will rock youFortune's Jeffrey M. O'Brien explains how Nintendo's new game machine won over the world - and beat the pants off Sony and Microsoft.(Fortune Magazine) -- Nintendo's legendary videogame designer Shigeru Miyamoto is lying face down on the floor in Kyoto, Japan, hobbled by a right cross and struggling to regain his composure. The man some credit with the very existence of the $30 billion videogame industry, the Walt Disney of our generation, has taken one blow to the face too many. I'm standing over the creative force behind Donkey Kong, Super Mario, Nintendogs and his latest worldwide sensation, the Wii. I goad him to get up for the rest of his beating. Clearly, one of us is taking our boxing match a bit too seriously. After all, it's not really Miyamoto who has crumbled but rather his avatar - his Mii, in Nintendo parlance. "Ohhh" is about all the man can muster as the clock runs out. Miyamoto puts down his controller and concedes defeat to finish a photo shoot.

I may have beaten him at his own game, but we both know who's the real winner here. Nintendo's newest contraption has performed exactly as designed, creating yet another Wiivangelist, this time a gloating gaijin 5,000 miles from home who not only got up off the couch to play a videogame but actually worked up a sweat. With this little victory Miyamoto and company gather more momentum in their quest to conquer worthier competition. Videogame controllers generally feature a bewildering array of buttons, and watching an avid gamer work the device, thumbs pattering across plastic, can be intimidating. By contrast the Wii's wireless, motion-sensitive remote, which Miyamoto had been dreaming of for years, often requires no button manipulation whatsoever. In the boxing game my 54-year-old host and I were bobbing and weaving and punching at air - jabs and crosses mostly. Miyamoto, whose official title is senior managing director, would angle his hands from one side to another to avoid haymakers; each time I missed, he'd giggle. And everyone in the room laughed along. While game consoles typically attract youngish males with an antisocial streak, the Wii is bringing people of all demographics together: in nursing homes, for Wii bowling leagues, on cruise ships, at coed (!) Wii-themed parties and, of course, in lines - as hordes of consumers clamor to buy the impossible-to-find $250 machine. Nintendo is churning out over a million units a month and still can't meet demand. At the Nintendo World store in New York City's Rockefeller Center, shipments arrive nightly. In the wee hours customers begin lining up around the block. Doors open at nine, and a few hours later the consoles are gone. In the world's gadget epicenter, Tokyo's Akihabara district, shopkeepers complain about the lack of inventory. Wii displays are covered with SOLD OUT signs, while piles of PlayStation3 boxes carry a different message: 5 percent OFF. Even the Nintendo of America company store near Seattle sees lines of employees, visitors and contractors. Forget about lucking into a Wii at your local Best Buy (Charts, Fortune 500). It's not unusual for a new game console to sell out during its pre-Christmas introduction, only to see sales dwindle come January. But six months after the Wii's launch, sales are accelerating. Nintendo sold 360,000 boxes in the U.S. in April, 100,000 more than in March. That's two Wiis for every Xbox 360 and four for every PlayStation3. While Sony (Charts) and Microsoft (Charts, Fortune 500) lose money on hardware in hopes of seeding the market with their consoles, analysts say Nintendo makes about $50 on every unit. It may not sound like much, but the company plans to sell 35 million of these things over the next few years. That's $1.75 billion in potential profit. Add that to the ridiculous earnings from the company's handheld gaming device, the Nintendo DS, as well as software sales and licensing revenue, and you begin to understand why Nintendo's market cap just passed $45 billion, an all-time high. (Nintendo (Charts) trades on the Tokyo and Kyoto stock exchanges and as an ADR in the U.S.) More difficult to comprehend is how a company founded 118 years ago as a maker of playing cards in Kyoto came to be pummeling Microsoft and Sony. The answer has something to do with reinvention. From industry-changing arcade machines to handhelds, 3-D graphics to immersive game play, Nintendo has shown a knack for leapfrogging its industry. Sure, some initiatives failed - a toy vacuum cleaner, a taxi service, a chain of "love hotels" - but the company rarely fails to surprise. And if the Wii shortage demonstrates anything, it's that this time, in changing perceptions of gaming, Nintendo has surprised even itself. In a quieter moment Miyamoto ponders that ability to chart a new course. "How Nintendo has been able to create one surprise after another is a big question even for me," he says. "I'd like to know the answer." New recruits The word "Nintendo" is an amalgamation of three symbols: nin, meaning "leave to"; ten, for "heaven"; and do, "company." The most common translation in Kyoto is "the company that leaves to heaven." What that means is open to debate. It could be a resignation to fate, as in "The company's destiny is in heaven's hands." But it's clear from a series of exclusive interviews with several executives over three months in Japan and the U.S. that little is left to chance. Another translation might be "Take care of every detail, and heaven will take care of the rest." The man who oversees every detail is president and CEO Satoru Iwata. Iwata, 47, started as a developer for a firm Nintendo bought in 2000. Since taking over in 2002 he has westernized Nintendo, instituting performance-based raises and a retirement age of 65. To hear suppliers and contractors talk, working with Nintendo is both frustrating and inspirational. It can be Wal-Mart-esque, driving down prices by playing parts manufacturers against one another while challenging them to be more creative. Employees talk breathlessly about loving their jobs while grumbling about hectic schedules. Everyone flies commercial. The one person permitted in first class, Iwata himself, has been known to slog to London and back in one day for a press conference. No hotel required. In short, Iwata has made Nintendo as efficient as a bullet train and as stingy as a bento box. The company's 3,400 employees generated $8.26 billion in revenue last year, or $2.5 million each. While exchange rates and fiscal calendars complicate comparisons to U.S. companies, let's do it anyway. Over roughly the same time frame, Microsoft employees generated $624,000 each; Google's performed 50 percent better, at $994,000, though still less than half as well as Nintendo employees. Nintendo's profits reached almost $1.5 billion, or $442,000 per employee, last year, compared with Microsoft's $177,000 and Google's $288,000. Such gaudy numbers aren't the result of mere penny-pinching. Mainly they're a product of the strategic course Iwata has set. When he took over, PlayStation2 was king, and Microsoft, with its Xbox, was challenging Sony in a technological arms race. But Iwata felt his competitors were fighting the wrong battle. Cramming more technology into consoles would only make the games more expensive, harder to use, and worst of all, less fun. "We decided that Nintendo was going to take another route - game expansion," says Iwata, seated on the edge of a leather chair, leaning over green tea in a three-piece suit, a strip of gray emerging along the part in his thick hair. He has an easy command of English but speaks through an interpreter. "We are not competing against Sony or Microsoft. We are battling the indifference of people who have no interest in videogames." The first test of the strategy came in 2004 with the Nintendo DS. Handhelds weren't a new concept. Nintendo had sold tens of millions of Game Boys. But Sony's forthcoming PSP was being touted as a multimedia machine rich in technology and with an ability to play movies. Iwata went cheaper, smaller (the size of the device), and broader (the intended market). The DS has side-by-side screens, one of which is a touchscreen; Wi-Fi; and voice recognition - all to make it approachable and communal. To put those features to use, Iwata conceived what would become one of the bestselling games for the DS, "Brain Age." Based on the brain-training regimen developed by a Japanese neuroscientist, "Brain Age" tests and improves mental acuity. With sales of more than 12 million copies, the title has made the DS a hit in such unlikely places as nursing homes. Iwata also oversaw development of a talking cookbook "game." And of course Miyamoto kicked in, creating the pet-care game "Nintendogs," which has moved more than 14 million copies. As of this spring the company has sold more than 40 million DS devices, compared with 25 million PSPs. So when it came time to launch the Wii, Nintendo already had a model to follow. Breaking the mold The typical life cycle of a game console goes something like this: Manufacturer produces or commissions the most sophisticated parts it can come up with and hopes to milk them for half a decade. Both the PS3 and Xbox 360, for example, have processors that are far more powerful than you'll find in most PCs. Each uses high-end graphics chips that support high-definition games; Sony even includes a Blu-ray DVD drive. The boxes are expensive at first. Hard-core game freaks pay dearly to have a console early, but sales really jump in years two, three and four, as Moore's law and economies of scale drive prices down and third-party developers release must-have games. By year five the buzz has begun about the next generation, and the onetime latest, greatest machine can be found at a local garage sale for $50. Rinse. Wash. Repeat. The Wii busted that mold. First, Nintendo used off-the-shelf parts from numerous suppliers. Sony co-developed the PS3's screaming-fast 3.2-gigahertz "cell" chip and does the manufacturing in its own facilities. Nintendo bought its 729-megahertz chip at Kmart. (Not really. But it might as well have.) Its graphics are marginally better than the PS2 and the original Xbox, but they pale next to the PS3 and Xbox 360. Taking this route enabled the company to introduce the Wii at $250 in the U.S. (vs. $599 for the PS3 and as much as $399 for the 360) and still turn a profit on every unit. And while a $250 sticker makes the Wii more of an impulse buy than even an iPod, it's not the pricetag that makes it fly off shelves. As with DS, the Wii comes with Wi-Fi, which gives customers access to the Internet, and features an incredibly addictive Mii channel. Players craft likenesses of themselves (or anyone else; the little cartoons you see throughout this article are Miis), which then appear in boxing, tennis, golf and other games. The only thing more fun than bowling in your living room with a bunch of friends is having their digital counterparts cheer you on from the alley inside your TV. The experience makes you forget about graphics altogether. You don't mind that your Mii is missing arms and legs. And of course the Wii has that innovative interface, the Wii Remote. The Wiimote, as it has come to be known, features a speaker, a rumble pack that makes the device shake, and even a mystery feature or two that have yet to be exploited, like a microphone jack. (Wii Karaoke perhaps?) But the Wiimote's magic really comes down to a $2.50 chip developed by a company in Cambridge, Mass., called Analog Devices Inc., (Charts) or ADI. Known as a three-axis accelerometer (see graphic), the chip precisely measures movement in three dimensions. At four square millimeters, several accelerometers would fit on your thumbnail. Prying open a Wiimote, ADI applications engineer Harvey Weinberg explains how the innards work. "This is actually a pretty cool piece of engineering," he says. "There's a Bluetooth link in here, a little bitty speaker, and an infrared camera. Of course the most important part is the accelerometer." The camera communicates with the light bar, which sits above or below the TV set. This is important because of a player's tendency to swing the remote wildly while, say, trying to hit a baseball 450 feet. Each time the camera faces the TV, the machine reestablishes a player's whereabouts. "The Nintendo guys were going to get large errors if they didn't figure out how to get absolute position," Weinberg says. "The camera resets the positional error. But they couldn't have gotten it to work with IR alone because most of the time you're not facing the TV. They couldn't have gotten it to work really good unless it was wireless. And they've aggressively chosen components that don't use a lot of power. The whole thing is synergistic." Nintendo designed dozens of prototypes before settling on the Wiimote. Miyamoto says early versions looked more like a control pad. Some were whimsical, some complicated. Designers arrived at the current version by coming back to Iwata's decree to battle indifference, not the competition. Miyamoto realized it wasn't a fear of gadgets that kept the average consumer from playing games. "TV remotes are always sitting out on a coffee table or on the sofa, but videogame controllers - people don't want them lying around," he says. "In that sense we thought we were losing to the TV remote. So we thought, What kind of controller can we create that won't make people afraid to touch it?" A gaming pioneer Under Miyamoto's creative direction Nintendo has never had a problem coming up with great games. Pok�mon, Super Mario, The Legend of Zelda - Nintendo titles have dominated the bestseller list for each Nintendo console. But that's not necessarily a good thing for the company. Third-party games increase consumer interest in the hardware, which sells more software. What's more, the console manufacturer gets a licensing fee for every third-party game sold, and it bears no development costs. "It really is pure profit," says Reggie Fils-Aime, the president and COO of Nintendo of America. "Third-party games can really determine who wins." Fils-Aime, an intense, 46-year-old Haitian-American, introduced the Wii at a trade show in 2004 by announcing, "My name is Reggie. I'm about kickin' ass, I'm about takin' names and we're about makin' games." That opening salvo lit a fire under the gaming media and Nintendo fanboys, and now Fils-Aime is trying to do the same in the game-development community. He's got a good pitch: Because the Wii isn't high-def, a game can cost as little as $5 million to develop, compared with up to $20 million for the PS3. That message, and the fact that the Wii is clobbering the PS3 in the marketplace, seem to be getting across. While Nintendo's own titles still top the Wii charts, third-party titles are selling well. Yves Guillemot, president and CEO of French game publisher Ubisoft, says Nintendo has become the top console maker to work with. Two of Ubisoft's games, Rayman: Raving Rabbids and Red Steel (in which you use the Wiimote like a sword), have sold nearly a million units each. "We looked at the capabilities of the Wii early on and saw that it was solving the most important element in the game industry - accessibility," Guillemot says. Both the Wii and the DS, Guillemot adds, have Ubisoft developers thinking creatively about what constitutes a game. Later this year Ubisoft will unveil "My Life Coach" and "My Word Coach," titles developed in collaboration with a behaviorist and a linguist, respectively. "Nintendo has been very open with us," says Guillemot. "They're willing to do things that are a bit crazy. They see what we want to do and help us to make it as good as possible." It took a while, but the industry's largest publisher, EA (Charts), has also come around to the Wii. At EA headquarters in Silicon Valley, developers glow at how the Wiimote opens a new aspect of games like "The Godfather" and "Tiger Woods". The company developed a new Wii-exclusive game, "MySims," due out in the fall; it is working with Steven Spielberg on a Wii title; and its latest FIFA soccer game will use Mii characters. "Nintendo is a pioneer," says John Schappert, COO of EA Studios. "They're zigging when others are zagging. It's another growth curve for the industry." "We are successfully moving up the blue ocean," Iwata says. "But once the blue ocean has become big enough for so many people to notice, it is going to change its color to red." The blue-ocean strategy Talk about lost in translation. Turns out there's a name for the line of attack Iwata has been taking: the blue-ocean strategy. Two years ago business professors W. Chan Kim and Ren�e Mauborgne published a book by that title. It theorizes that the most innovative companies have one thing in common - they separate themselves from a throng of bloody competition (in the red ocean) and set out to create new markets (in the blue ocean). Starbucks is an example. There's always been coffee; Howard Schultz gave us the coffee experience. Or Apple, which gave us the iPod and iTunes - and created a new form of entertainment. Iwata set his course before the book was published, but now that he's read it, he feels validated. "Even before someone invented the term blue-ocean strategy, we were exercising it," he says. "It is an unwritten company credo, something that runs deep in our DNA." The Wii's success has done little to convince Microsoft executives they're on the wrong course. The company is positioning itself for a world where people play multiplayer games, download movies and control their TVs through one box. "Nintendo has created a unique and innovative experience," says Peter Moore, who runs Microsoft's Xbox business. "I love the experience, the price point, and Nintendo content." But Microsoft, Moore adds, "provides experiences that Nintendo cannot provide." Of course Microsoft has little more to lose than money, and there's plenty of that to go around. Sony is another matter. Gaming has been the company's profit center for years. Suddenly, when everyone thought the PS3 would solidify Sony's dominance, along came the Wii. With an unheard-of price and few quality games to choose from, the PS3 has produced disappointing sales; the father of the PlayStation, Ken Kutaragi was recently forced to resign his post as chairman of Sony Computer Entertainment. But while he acknowledges a slow start, Jack Tretton, the president and CEO of Sony Computer Entertainment America, thinks it's too early to start talking winners. "You have to give Nintendo credit for what they've accomplished," says Tretton, who's quick to point out that Sony has come out with some innovative controllers too. "But if you look at the industry, any industry, it doesn't typically go backwards technologically. The controller is innovative, but the Wii is basically a repurposed GameCube. If you've built your console on an innovative controller, you have to ask yourself, Is that long term?" Iwata knows the Wiimote alone won't sustain Nintendo forever. But Tretton's question nicely encapsulates two distinct approaches toward innovation. Despite the fact that the PS2, with its seven-year-old innards, is still the top-selling game console, Sony views the world through the eyes of an engineer, seeing an impressive proprietary technology (Betamax, Memory Stick, Blu-ray) and foisting it on the market. From that point of view, less technology is always a step backward. Nintendo takes its cues from the outside world - Miyamoto's garden, for example, which was the inspiration for the Nintendo game Pikmin. Or from the behavior of everyday people, like the way we leave our TV remotes on the couch. In Miyamoto's eyes technology is just a tool, and less of it is often more. "What I want to do," he says, "is to make it so people can actually feel something unprecedented." So what's next for this company, so full of surprises? The Wii gives Nintendo a few options. It could stick with the current Wii for a few years until today's top-end technology falls to Kmart prices. At that point it could introduce a Wii 2.0 with technology similar to today's PS3, but on the cheap. It could cut $50 off the sticker to compete with the price cuts that are undoubtedly coming from Sony and Microsoft. But that's red-ocean thinking. Iwata wants to keep innovating, to do for gaming what Starbucks has done for coffee or Apple has done for music. "The relationship with the Mac or PC to iTunes and the iPod," he says, "that kind of combination may be possible between DS and Wii." Until Nintendo gets more Wiis on retail shelves, all that is theoretical. Iwata says no single bottleneck has caused the shortage, and that has made the problem harder to solve. Because it was targeting a market that didn't exist, the company had no idea how popular the machine would be. And nobody could have known the Wii would still be selling so well as summer approaches. That kind of thing just doesn't happen in the Christmas-centric world of gaming. "We cannot simply make 1.5 times as much or two times as much," he says. "When you're making one million a month already, getting to 1.5 million or two million is not very easy." No, not easy. But necessary. So hurry up, Nintendo. My grandma is waiting. From the June 11, 2007 issue

|

Sponsors

|