The hidden workplaceThere's the organization chart - and then there's the way things really work. Some smart companies are bringing power structures out of hiding, reports Fortune's Jennifer Reingold and Jia Lynn Yang.(Fortune Magazine) -- Anyone who has ever worked knows that the org chart, no matter how meticulously rendered, doesn't come close to describing the facts of office life. All those lines and boxes don't tell you, for example, that smokers tend to have the best information, since they bond with people from every level and department when they head outside for a puff. The org chart doesn't tell you that people go to Janice, a long-time middle manager, rather than their bosses to get projects through. It doesn't tell you that the Canadian and Japanese sales forces don't interact because the two points of contact can't stand each other. In every company there is a parallel power structure that can be just as important as the one everyone spends stressful days trying to master. Jon Katzenbach, founding partner of New York City-based consulting firm Katzenbach Partners, and his colleague, principal Zia Khan, have spent the past several years trying to bring the shadows to light. In a study released exclusively to Fortune, "The Informal Organization," they argue that successful managers must understand this "constellation of collaborations, relationships, and networks," particularly in times of stress and transition. "We're not saying you can formalize the informal," says Katzenbach. "We're saying you can influence it more than you do."

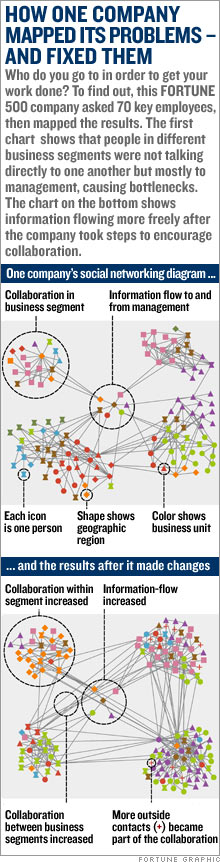

In a recent survey conducted for Katzenbach, a third of the 390 respondents - all of them working at large U.S. companies - admitted ignoring the rules when they found a better way to get things done. And in companies where managers worked closely with informal employee networks, respondents were three times more likely to describe their job environment as positive. The upshot: Going by the book is not always the way to get results. Nor can you simply set up a bunch of Ping-Pong tables and let people groove to their own beat; supervision and leadership matter. Katzenbach calls the ability to toggle between both power structures "organizational quotient," or OQ. At first blush, much of this will sound obvious. But while managers may be aware of the hidden workplace, many are clueless about how to make it function for them. One of the most effective tools to navigate this territory is social network analysis, which graphically delineates relationships between employees, bosses, and units. "You're able to bring data and fact and statistics to the table, as opposed to rumor, emotion, or anecdote," says Tracy Cox, director of performance consulting at Raytheon. Other companies are engaging the shadow organization without trying to control it. After all, the strength of the thing is mainly in its squishiness. The examples that follow show how several companies have turned to their informal power structures to attack some classic business issues. PROBLEM: Energizing a sluggish culture In 2002, Bell Canada's new CEO, Michael Sabia, inherited a struggling 122-year-old company that needed to banish its monopolist mentality in order to compete. To make his employees more outward-looking, dynamic, and productive, Sabia started with traditional business moves, such as implementing a Six Sigma program and cutting costs. They weren't enough. Culture change can start in the corner office, but it cannot end there: "We needed to get to the front lines of the organization," says Sabia, "and my view is that it's very hard to do that through formal programs." Working with Katzenbach, as well as chief talent officer Leo Houle and Mary Anne Elliott, SVP for human resources, Bell Canada decided to try to cultivate change from within. Using surveys, performance reviews, and recommendations from executives, it scoured its nearly 50,000 employees to find 14 low- and mid-level managers who embodied the mentality the company sought: committed, passionate, and competitive. Katzenbach and staffers in the HR department interviewed the 14 extensively. They found that the subjects shared the ability to get people to trust them and to solve problems rather than complain about them. "These people have incredible influence," says Elliott. "It's like the [Life cereal] commercial - Will Mikey eat it?" The initial group then recommended another 40 associates. In September 2004, Bell Canada organized an all-day meeting in Toronto for these "Pride Builders," including a session with Sabia, who bluntly asked them to lead a cultural transformation. "When we were brought into this environment," says Valerie Belzile, one of the original 54 and now associate director for corporate client care in the wireless unit Bell Mobility, "there was no more hierarchy. I felt, 'Oh, my God, this is real."' The group gradually grew to 150 people, who created their own "community of practice" in which they shared ideas. They also worked on problems identified during company-organized gripe sessions and determined future conference topics themselves, such as managing people from different generations. At one, they handed Sabia a list of "pain points" he was unaware of - such as the bureaucracy associated with bringing in new hires. The Pride Builders helped shorten the process from as much as six weeks to five days. Ironically, the Pride Builders' success has made it a much more formal organization. Today it has morphed into a veritable army of 2,500 people in 25 local chapters; three full-time staffers take care of administrative tasks. Belzile is co-coordinator of a chapter and organizes a monthly lunch to share best practices. Has it made any difference? There are some quantifiable results. Starting in the fall of 2005, the company measured the impact of "pride behaviors" on customer and employee satisfaction in its small and medium-sized business call centers. Relative to the control group, employee satisfaction rose dramatically, as much as 71 percentage points. Customer satisfaction jumped too: Percentage increases ranged from 35% to 245%. "A formal organization is responsive to the exertion of power," says Sabia, "but an informal organization is responsive to persuasion. It's changed the way I think about management." Investors' views of the company have changed too: At the end of June, Bell Canada's parent went private in a $33 billion deal - the largest such transaction in Canadian history. PROBLEM: Grooming leadership Investment bank Lehman Brothers (Charts, Fortune 500) is a notoriously competitive company in a hypercompetitive industry. But now Lehman is putting more emphasis on OQ in its efforts to identify and retain top talent. "It has to do with people trusting one another and understanding how to bring all the parts of the firm together for a client," says Hope Greenfield, Lehman's chief talent officer. One resource is the work of Rob Cross, a former IBM and Andersen Consulting manager now at the University of Virginia's McIntire School of Commerce. Cross runs the Network Roundtable (networkroundtable.org), which studies social network analysis. The roundtable has grown to 80 members in two years, including Lehman, Merck, Intel, and the U.S. Navy. Its members meet regularly to share data and results. In 2006 Lehman managers identified 300 vice presidents as top performers and sent them to a four-day leadership workshop. Then, last April, Lehman brought them to New York City for the company's first social network analysis to help the participants understand and improve their existing networks. "We're not doing this just because we think it will make them happy," says Greenfield. "We think it will have an impact on both the firm's and their financial success." Everyone in the group took a customized 15- to 20-minute survey, developed by Cross, that asked each person to identify whom they relied on for information and which collaborations led to increased revenues. Cross then generated a graphic for everyone, a web of nodes and networks that allowed each executive to see who is connected to whom. The analysis assessed the strength of each person's network relative to others in Cross's database. It also mapped information flows. Several types emerged, including "connectors," who had the most extensive direct ties, and "brokers," who had the most diverse networks and who were key to getting things done. Then there were the "bottlenecks," who - either because they were overworked or because they hoarded information - kept things from happening. All the employees were able to see if they were on the periphery of networks or in the middle of them. By learning how to interpret the results, the Lehman executives picked up the tools to build themselves a better network. (Contrary to conventional wisdom, this does not necessarily mean building a bigger one, Cross cautions; a network that is too big, he has found, can lose power.) The objective, says Greenfield, was to encourage - but not to force - informal ties between the executives. Lehman was intrigued enough that it is now considering mapping relationships with clients. If the message takes, Lehman believes the executives will be more productive, happier, and ultimately more successful. That is not as quantifiable as trading revenue, but then, that's the point. The event ended with an inspirational speech by the ultimate networker - Bill Clinton. |

Sponsors

|