Can the Washington Post survive?Newspapers are dying. At the Washington Post Co., CEO Donald Graham is banking on the Internet to save serious journalism. If he can't figure this out, nobody can. Fortune's Marc Gunther reports.(Fortune Magazine) -- Barry Svrluga, a 36-year-old baseball writer for The Washington Post, was on his way to the barber when an e-mail pinged his BlackBerry telling him that the Washington Nationals had sent two struggling pitchers to the minor leagues. Svrluga detoured to Starbucks, wrote a 572-word commentary on his laptop and posted it to his blog, Nationals Journal at washingtonpost.com. After his haircut he swung by the Post's newsroom to do a live question-and-answer session online with fans. That night, after filing a story for the newspaper, which he calls the "$0.35 edition" in his blog, Svrluga recorded a ten-minute podcast for the Web site, with sound bites from team officials and players. Like most reporters at the Post, Svrluga has become platform-agnostic, which is a nice way of saying that his bosses are no longer big believers in print. Today a small army of bloggers, podcasters, chatroom hosts, radio voices and TV talking heads, as well as a few old-fashioned ink-stained wretches, populates the newsroom at the 131-year-old Post. They understand that Donald E. Graham, the chairman and CEO of the Washington Post Co., is hurrying the paper into the digital future. "If circulation is dropping," Svrluga explains, "and we're trying to figure out how people are going to get their news, who am I to say no to trying out new avenues?"

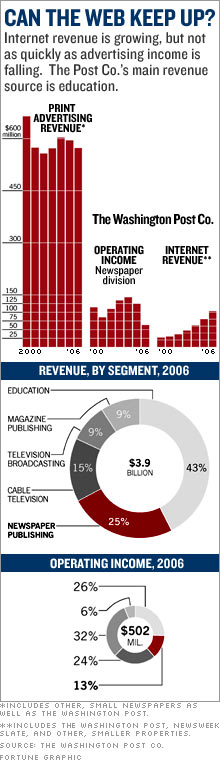

New avenues: That's the story of the newspaper business right now. Alarmed by declining circulation, advertising and profits, America's newspaper publishers - as hidebound a collection of businesspeople as you can find - are thrashing about to see whether they can separate the news from the paper and still make money. They're going way beyond the headlines. A Web site for college students called BigLickU from the Roanoke Times! Another for busy moms from the Dallas Morning News! Restaurant coupons from the Palm Springs Desert Sun's FoodPsycho.com! Innovation! Disruption! Transformation! These are the new buzzwords of an industry whose last big idea was the invention of USA Today. In 1982. Can newspaper publishers turn the Internet from a threat into an opportunity - as Rupert Murdoch wants to do with his $5 billion bid to buy Dow Jones (Charts), owner of The Wall Street Journal? It's a long shot, but it's their only hope. Their plight is something not often seen in business: Newspapers remain important institutions, providing a valuable public service, but their business model is slowly, or maybe not so slowly, going away. No less a sage than Warren Buffett, a lifelong newspaper aficionado, the owner of the Buffalo News, and a director of the Washington Post Co. (Charts) for most of the past 35 years, told Fortune, "The present model - meaning print - isn't going to work." The Washington Post, a first-class newspaper that dominates its local market, has the best shot of any at reinventing journalism for the Internet. Since the mid-1990s, the Post has plowed many millions of dollars into its interactive unit, taking readers to unexpected places. They can join a lively global debate about religious faith, read hyperlocal coverage of a fast-growing Virginia county or watch daily video programs from the digital magazine Slate. Graham has made the paper's digital business his uppermost priority. "If Internet advertising revenues don't continue to grow fast," he says, "I think the future of the newspaper business will be very challenging. The Web site simply has to come through." The problem facing Graham is easy to understand but hard to solve. The pillars of the Post, revenues from display and classified advertising, are declining faster than its Internet business is growing. For the first five months of 2007, total ad sales, including print and online, are down by 12 percent. Other newspapers, too, are reporting sharper drops in ad revenue lately than anyone in the business had expected. Profits are shrinking too. Operating income for the Post Co.'s newspaper division fell from $125.4 million in 2005 to $63.4 million in 2006. (Most of the decline was caused by a $47.1 million expense for early-retirement buyouts.) In the first quarter of 2007, operating income for the newspaper unit fell by another 53 percent. What lies ahead for the Post seems to be a long and painful transition from print - so important to local advertisers that the newspaper could raise prices almost at will - to the Internet, where competition for readers and advertisers is brutal. The best evidence of the difference is the fact that advertisers paid about $573 million last year to reach readers of the company's newspapers, predominantly the 673,900 daily and 937,700 Sunday subscribers to the Post. Advertisers paid only about $103 million to reach the eight million unique visitors to the Post's Web sites each month. To Graham, this is more than business; it's personal. His grandfather Eugene Meyer bought the Post for $825,000 at a bankruptcy sale in 1933. (Hard times are not new to the business.) His father, Philip Graham, diversified the firm by buying TV stations and Newsweek. His mother, Katharine Graham, reigned during its Watergate glory. That makes Don Graham both the trustee of a family fortune and the steward of a journalistic tradition - responsibilities that he takes to heart and that are not always easily reconciled. "The Post is a business, and it is something more," he says. Graham, 62, is a reticent and self-effacing man. He would not be photographed by Fortune, and only reluctantly did he sit for an interview. "I'm not the center of the story," he demurs, crediting others for the company's successes. But Graham is intelligent, analytical and disciplined, and he, more than anyone, has put the Post in a position to work through the industry's crisis. Why is the Post Co. in better shape than its peers? Luck played a role. In 1984 the company bought a small test-preparation business from a Brooklyn entrepreneur named Stanley Kaplan, not really knowing what it was getting. Today the Kaplan education division is the company's largest and fastest-growing business, and it has shielded the Post Co. from the kind of shareholder pressure that forced the breakup of Knight Ridder and the Tribune Co (Charts, Fortune 500). But Graham also had the foresight to steer the Post Co. away from print as other companies spent billions buying into it. An outstanding board of directors, whose members include Barry Diller, Melinda Gates and Graham's most important advisor, Buffett, has been a big help. So has Graham's reputation as a benevolent owner, which has attracted great writers and editors to the Post. Finally, the Post is published in the most affluent and educated region in the country; in the nation's capital, much of the business that gets done depends upon the news. Here's the point: If Graham and his people can't build a business model for journalism in the digital world, nobody can. A lasting legacy On Sunday, Feb. 17, 2007, the Post published a 4,700-word story by Dana Priest and Anne Hull, the first of a series to document the neglect of wounded Iraq war veterans, particularly at the Army's top medical facility, Walter Reed Army Hospital. Their work set off congressional hearings and brought about the dismissal of the Army Secretary and two generals. "This is what we are all about," says Priest, 49, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 2006 for stories that exposed secret CIA detention centers overseas. "You could not do it as a blog," she adds - though the Walter Reed story was certainly amplified by the Web. About 25 people, including nine Pulitzer Prize winners, make up the Post's investigations unit. "Investigative reporting is our brand," says Jeff Leen, the editor who leads the group. In the past few years, the Post broke open the Jack Abramoff corruption scandal, examined Vice President Cheney's behavior in office, exposed mismanagement at the Smithsonian Institution and chronicled farm subsidies that go to the rich - all part of what the paper's executive editor, Leonard Downie, calls "accountability reporting." The engraving plate from the Aug. 9, 1974, front page, with its enormous headline - NIXON RESIGNS - hangs in the room where Post editors meet daily. As a local newspaper with global ambitions, the Post is a holdover from earlier, inkier times. The paper maintains 20 to 25 overseas correspondents in 19 bureaus, and they are well trained. Before Fred Hiatt, who is now editorial-page editor, was dispatched to Moscow years ago, he took a yearlong paid sabbatical to study Russian and the Russians. It's no trivial matter to cover a foreign power for a newspaper that sits on the breakfast tables of cabinet secretaries and members of Congress. Top journalists have flocked to the Post since the days when the swashbuckling editor Ben Bradlee ran the place and Woodward and Bernstein were lionized in the movie based on their book, "All the President's Men." Katharine Graham - the first female CEO of a Fortune 500 company - guided the paper through the 1971 publication of the Pentagon Papers and Watergate. She was an astute businesswoman too. In 1971 the Post Co. went public at $6.50 per share (adjusted for a subsequent four-for-one split). Twenty years later, when Mrs. Graham turned the CEO job over to her son, the price was $222, a gain of 3,315 percent, ten times more than the Dow. Like the New York Times Co. (Charts) and Dow Jones, the Post Co. has two classes of stock, with control resting in the family-owned shares. The biggest outside shareholder is a friendly one: Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway, with 18 percent of the publicly traded shares. Don Graham's direct stock holdings in the company are worth roughly $350 million. Money, though, is not what drives the CEO. "He's a very duty-bound person," says Boisfeuillet "Bo" Jones Jr., a lifelong friend who is publisher of the Post. After college Graham joined the Army, serving in Vietnam as an information specialist, and then returned to Washington to join the D.C. police force. For about 18 months he patrolled a beat on the city's poor northeast side, a world away from his childhood homes in Georgetown and Virginia's hunt country. To his mother's relief, he joined the Post in 1971 as a metro reporter. He was named publisher in 1979. By then - long before Yahoo or Google News - the newspaper business had begun what Jack Shafer, Slate's press critic, has termed its "slow, unstoppable, train ride to hell." (Yes, the Post Co. pays his salary.) In 1976 the Los Angeles Times published a page-one story about newspapers that began, "Are you holding an endangered species in your hands?" |

Sponsors

|