NEW YORK (CNN/Money) -

It is hard to even remember the euphoria that gripped the country in March 2000, the way investors' only fear was that the market would leave them behind and that the only trend was up. It is harder still to wrap your head around how, in three short years, things got so terribly bad.

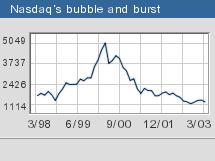

When the Nasdaq composite index closed at its record high of 5,048.62 on March 10, 2000, it had in the space of just one year more than doubled. The unemployment rate had just come in at 4.1 percent and the latest read on gross domestic product showed the economy growing at a 6.9 percent annual rate. Weeks before, Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan told Congress "beneficent fundamentals will provide the framework for continued economic progress well into the new millennium."

But most people could do without the progress, if that's the right word for it, of the past three years, a period of a weakened economy, slumping profits and steep stock market losses that has left the country in the grips of a creeping uncertainty that only deepens the malaise. The virtuous cycle has turned vicious and it's hard to see what's going to shift it back.

Once in a lifetime

The Nasdaq, down 75 percent from its peak, doesn't lead the evening news anymore, but for many observers the malaise both the market and the economy have fallen into have everything to do with the Nasdaq's rise and fall. The tech-laden index stood at the center of an investing binge unlike anything seen in this country for 70 years.

"How did we get where we are? Ask how we got where we were in 1932," said Northern Trust chief U.S. economist Paul Kasriel. "Ask how Japan got where it was in the early 1990s. This is what happens when bubbles burst."

As with all bubbles, it was about more than just stock. Old economy companies tried to tart themselves up with new economy paint by spending wildly on technology. Start-ups that were, with hindsight, plainly ridiculous, got handed armloads of cash. People entrusted their futures to the stock market, shifting more and more of the money they planned to retire on into tech shares.

"You started with a market that was grossly overvalued and well exceeded the high end of its trading range, its historical P/E and everything else," said Janney Montgomery Scott Vice President Larry Rice, who was bearish at the time. "When that happens, everything becomes artificially inflated."

The imbalances caused by the bubble only became fully apparent when it began to deflate. Companies found that they spent as though the good times could roll on forever and saw that it had left them with more production capacity than they needed and, what was worse, saddled in debt. Investors found that many companies had simply lied about their results, in some cases their entire businesses. And so there were debacles like Enron, Tyco and WorldCom.

In short, the country learned the boom years were something of a lie.

"Making very optimistic assumptions about earnings, I thought the Nasdaq was 75 percent overvalued in early 2000," said Cliff Asness, managing principal at the hedge fund AQR Capital Management. "But, given how financially, morally and offensively stupid prices were back then, it's entirely reasonable that even after falling so much, things are not cheap now. The shock is not how much we've fallen, but how greedy and stupid we were a few years ago."

Nasdaq 1,000?

The worry now is that, hard as the past three years have been, the bitter draught isn't finished. Many of the bears of 2000 believe that neither the market nor the economy are close to out of the woods.

"In my mind it still isn't over, because there's this continued fascination with Nasdaq and tech," said Merrill Lynch chief investment strategist Rich Bernstein, who went from being a long-time bull on the market to a bear in 1998. "[People's] biggest fear is that it's going to turn and they're going to be left behind."

Shares of the Nasdaq-100 Trust -- the QQQs -- regularly top the volume boards. Reams of paper get dedicated to technology, which is far more written and talked about than any other sector. But what tech and the market really need, thinks Bernstein, is a period of benign neglect, a time when the anniversary of the Nasdaq top comes and goes and nobody notices.

Doug Cliggott, who as J.P. Morgan's U.S. equity strategist went negative on the market in early 1999, pronounces himself as surprised at how well the economy is doing. Now head of U.S. research for the hedge fund Brummer & Partners, he says if you had told him in March 2000 that in three years' time the Nasdaq would be down 75 percent from its top, that the yield on the 10-year bond would be below 4 percent, that gold would be up 50 percent and the Federal Reserve would have cut the fed funds target rate to 1.25 percent from 5.75 percent, he would have supposed the economy would be in a deep recession. Maybe worse.

Instead, the economy is growing -- albeit slowly -- after what appears to be a minor recession. The reason? People took advantage of low mortgage rates and still-strong housing prices to take equity out of their homes, and then they used that money to help support their lifestyle.

Although that's softened the economic blow, thinks Cliggott, it also means that the adjustment process from the bubble days isn't complete. It's not as bad as it was, but Americans are still spending more than they earn. The savings rate needs to go up, which means that spending needs to come down. That suggests sluggish economic and profit growth over the next one to three years.

"I would guess we'll end up going through 1,000 on the Nasdaq before everything is said and done," said Cliggott.

Water at the bottom of the ocean

Not all the old bears are so glum. Asness thinks tech is still too pricey, but if investors are comfortable with somewhat lower returns than stocks have offered historically, the overall market is "at the upper range of fair value."

And though he was once dubbed "The Bear of Boca" by The Wall Street Journal, Seabreeze Partners head Doug Kass has had a change of heart. The hedge fund manager sees the current environment as the near-polar opposite of what reigned in March 2000. The recent sharp drop in consumer confidence, he thinks, marks a final give-up, and he points out that past drops have preceded large rallies.

He believes that with a resolution in Iraq, oil prices will plunge, serving as a tax cut for consumers and energy dependent businesses, confidence will rebound, the risk-aversion that's bound up the economy will fall away, profits will recover and stocks will rise.

"Investors have given up," he said. "They're basically saying nothing can turn this Titanic of an economy around just at the time where it's probably going to turn around."

|