NEW YORK (CNN/Money) -

When the Federal Reserve hinted this week that another interest-rate cut might be coming, U.S. stock prices rallied. But the already-shrinking dollar fell even more -- just another episode in the lonely plunge of the greenback, which many analysts say is only going to get worse.

On the surface, the stars would seem to be aligned for a strong U.S. dollar. The United States, in a league of its own militarily and economically, stands astride the world, this era's capital-E Empire.

Despite corporate accounting scandals, its markets are the biggest, most liquid, most investor-friendly in the world. And despite a recent slump, its stocks seem to be coming back and its economy has an explosive cocktail of stimulus in the pipeline.

Yet even after the Fed warned Tuesday of the risk of deflation, an unstoppable drop in prices that by definition makes dollars more and more valuable, the dollar fell into a fresh four-year trough against the euro.

What gives?

For one thing, the prospect of interest rates, already at 41-year lows, staying in the gutter indefinitely will discourage foreign investors from buying interest-bearing U.S. assets, such as bonds.

After all, why go shopping for interest-rate products in the United States, where the Fed's target rate is 1.25 percent, when you can shop for them in Europe, where the European Central Bank's target rate is twice as big, at 2.5 percent?

"The decision to shift to a weakness bias should trigger further dollar weakness across the board, as the United States remains a funding currency against the higher yielders like the Canadian dollar, Australian dollar and New Zealand dollar," said HSBC Bank USA currency strategist Meg Browne.

| Related stories

|

|

|

|

|

More abstractly, some traders might worry the Fed's warning of deflation -- despite interest rates at 41-year lows, which should be inflationary -- makes the United States look less like ancient Rome or Queen Victoria's Britain and more like 1990s-era Japan.

In Japan, policy-makers have slashed interest rates to near zero, and the government has poured money into the economy, but deflation and economic weakness have persisted for the better part of a decade.

"If you have deflation when interest rates are at 5 percent, it's no biggie," said Ashraf Laidi, chief currency analyst at MG Financial Group, a currency trading firm in New York. "But if you have deflation when interest rates are at 40-year lows, that spells the word 'Japan,' and that's not good. It highlights the possibility that the Fed's armory to bring the economy to a safe landing may have been used up."

Payback time

To be sure, the dollar, like Icarus, has flown very high in recent years and was destined to fall to earth. The currency gained about 47 percent during an amazing seven-year run, fueled by the late-1990s boom and then a flight to the relative safety of U.S. assets in the months after Sept. 11, 2001.

Since peaking in early 2002, however, the dollar has lost about 20 percent of its value, according to the Dollar Index, a measure of the greenback's performance against other currencies -- and could still have further to fall.

"The structural dollar descent is roughly half-way complete, [and] over the coming 18 months, the Dollar Index...may need to fall by another 10 to 15 percent," Morgan Stanley economists Stephen Jen and Fatih Yilmaz said in a recent note.

Interestingly, while this view is more or less seen as gospel in the rest of the world, it's not the majority view in the States, according to Merrill Lynch's April survey of 314 fund managers, both foreign and domestic.

In that survey, when asked to pick their "favorite currency," 65 percent of global respondents picked the euro. Their least favorite? For 57 percent of the world, it was the greenback.

And a whopping 66 percent of overseas fund managers thought the greenback was still too dear, despite its recent decline. In comparison, only 34 percent of U.S. respondents thought the dollar was overvalued.

Twin deficits loom

Certainly, U.S. confidence about the dollar's strength is in many ways warranted -- it seems highly unlikely to most analysts that foreign investors will totally abandon U.S. markets.

"The United States is the world's leading country in terms of markets and economy," said Florent Brones, an equity strategist at BNP Paribas in Paris. "Even if the dollar continues to decline, the United States will continue to be the leader, and the U.S. stock market will continue to lead European stock markets."

Nevertheless, overseas investors seem to have little appetite for dollar-denominated assets. The Merrill Lynch survey showed 56 percent of overseas fund managers thought U.S. equity markets still the most overvalued in the world -- compared with just 24 percent of U.S. managers.

This is ominous news, in the sense that foreign money is the drug the American economy desperately needs to function normally. The U.S. current account -- a measure of the money flowing into and out of the country that includes the trade of goods and services -- ran a whopping deficit in 2002 of $503 billion, or about 5.3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). That percentage is expected to climb even higher in 2004.

Throw in the surging deficit in the federal budget, which is likely to approach $400 billion, or more than 4 percent of GDP, this year, and you have the recipe for a "twin deficit" scenario worse than the one that preceded trouble for the dollar and U.S. stocks in the late 1980s.

Such deficits aren't a problem as long as overseas investors keep pumping money into U.S. assets, financing America's ability to live beyond its means. If foreign investors start looking elsewhere, however -- as they've already begun to do -- stock and bond prices fall, bond yields and interest rates rise, slowing down borrowing and economic growth, and the dollar falls even further.

"The deficits were a moot point in the middle of the dollar-positive landscape that started in the mid-1990s," said Laidi of MG Financial Group. "Foreign investors couldn't pull out or dare ignore the returns in dollar assets. But now, there is a whole different equation -- that's why the deficit is now a concern."

In the Merrill Lynch survey, 42 percent of foreign fund managers said the swollen U.S. current account deficit worried them enough to make them hedge some or all of their exposure to a possible dollar decline. Just 21 percent of U.S. respondents had done the same.

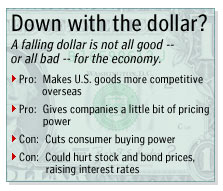

A little bit of dollar pain wouldn't be a bad thing for the U.S. economy -- weaker dollars make U.S. goods more competitive overseas, and keep prices higher at home, boosting corporate profits -- which is why the Fed and Treasury Department have pretty much ignored the dollar's fall.

Too much of it, however, would be disastrous, triggering an ever-faster retreat from dollar-denominated U.S. assets.

"Falling currency has worked wonders for a lot of countries, like Indonesia and Argentina," said Paul Kasriel, senior economist at Northern Trust in Chicago, sarcastically referring to nations devastated by a plunge in currency value.

"[Policy makers think] the falling dollar will solve all their problems. It makes profits look better -- even though companies aren't selling as much -- when they translate stuff into a depreciating currency. But the dollar could plunge if foreign investors pull out."

Technical factors also weigh on the dollar

Finally, there are other technical factors turning overseas investors away from dollar-denominated assets, according to Hans Redeker, global head of currency strategy research at BNP Paribas in London:

- Like U.S. companies, many European firms have also been trying to repair their balance sheets, which has caused some of them to sell their U.S. assets to bring their money back home.

- Some foreign investors are banking on certain stocks, called "beaters," which were volatile on the way down and could be equally volatile on the way up, thus offering a chance for a greater reward. Since many of these stocks are overseas, money is flowing away from the United States to try to catch the wave.

- Though U.S. potential economic growth is still strong, it's seen as being weaker than in the late 1990s, while European potential growth has stayed about the same. In relative terms, the economy's advantage is not as great.

Combined with the other factors weighing on the dollar's value, the stars could be aligned for something less benign than a simple dollar retreat -- a collapse is a possibility that can't be ignored, especially if the economy remains weak and stocks fail to rebound.

"There are substantial risks in U.S. dollar markets -- we might enter the freefall of the U.S. dollar," Redeker said. "That is a 35 percent probability."

|