|

The Biggest Company in America... is also a big target

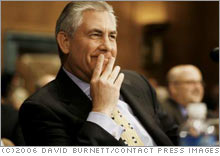

NEW YORK (FORTUNE) - The barons of big oil filed warily into the ornate Senate hearing room and raised their hands to be sworn in. Spotlights glared, cameras clicked, and members of the Senate Judiciary Committee leaned in for the kill. Standing at the back of the room were two dozen college students wearing EXXPOSE EXXON T-shirts. It promised to be a classic showdown: politicians browbeating petroleum CEOs for earning record profits while ordinary Americans were being squeezed at the pump.

The only problem was that Rex Tillerson hadn't bothered to read the Senators' script. Despite the best efforts of lawmakers who normally interrupt with impunity, the new CEO of Exxon Mobil (Research) made it clear that he was not about to be bullied. One after another, voluble Senators like Arlen Specter and Charles Schumer tried and failed to talk over Tillerson, who answered their queries in a deep Texas baritone befitting his background as a lifelong oilman and rancher. Even Joe Biden, who has been known to interrupt himself, had to wait until Tillerson was finished before lobbing another question at the imperturbable CEO. "We are investing heavily in conventional oil and natural gas, which is the business we are in," Tillerson said, when asked why Exxon was spending so little on renewables such as ethanol. "We are not in those other businesses." Nor would Tillerson apologize for his company's record haul at a time when Americans are paying $2.50 a gallon for gasoline. Those $36 billion in profits, he told the Senators, "accrue to the more than two million individual Americans who own our shares." And in case anyone in the room missed his point, Tillerson added, "I suspect people on this committee benefited from our success last year." (He's right: Arizona Republican Jon Kyl is an Exxon shareholder, according to recent financial disclosures.) It's that same steely authority that catapulted Tillerson, 54, to the top of Exxon at the end of last year, when he succeeded the legendary Lee Raymond. It's also typical of the toughness that enabled Exxon to capture the No. 1 spot on the FORTUNE 500 for the first time since 2001, supplanting recent champion Wal-Mart. With $339.9 billion in revenue and profits of $36.1 billion, Exxon earned more than any U.S. company in history last year—more than the profits of the next four companies on the FORTUNE 500 combined. Exxon's return to No. 1 caps its emergence as not only the biggest but also the most powerful U.S. corporation by just about any metric. Last year it surpassed General Electric to become the most valuable U.S. company by market capitalization ($375 billion). It pumps almost twice as much oil and gas a day as Kuwait, and its energy reserves stretch across six continents and are larger than those of any nongovernment company on the planet. This year Wall Street expects it to spend roughly $15 billion on exploration and production, buy back at least $20 billion in stock, and pay $8 billion in dividends, all without having to raid a cash hoard that exceeds $30 billion. Exxon's power now echoes that of John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil, the trust whose breakup by the government nearly a century ago spawned not only Exxon and Mobil but also Chevron, Conoco, and Amoco, and marked the beginning of a new era in Washington's regulation of business. This time the stakes are just as high. As its profits multiply, Exxon is drawing increased criticism for its stance on global warming and its support of drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Schumer may not have been able to interrupt Tillerson, but he clearly would like to remind him that Exxon's power isn't unlimited. "Exxon's attitude is that they're the big boys on the block, and they don't have to bend for anybody," the New York Democrat told FORTUNE after the hearing in March. "But there is no question there is a new phase of scrutiny for Exxon. If I were giving them advice, it would be, 'Get used to it and prepare for it.' They have a self-righteousness that sooner or later will catch up with them." If Exxon's leadership is arrogant, as Schumer claims, it could be because they know their company is the best-run energy firm in the business. As Royal Dutch Shell struggles to replace the oil and gas it pumps out of the ground and watches its production sag, Exxon has replaced more than it has produced for the last 12 years. Since 2004, its stock has outperformed BP's (Research) and Chevron's (Research). And while BP tries to change the subject by claiming it's Beyond Petroleum, Exxon offers no apologies for being in the oil business. Whether you love 'em or hate 'em, understand that Exxon's rise to the top of the FORTUNE 500 wasn't just a function of high oil prices. Sure, $65-a-barrel crude helped, but the real reason for the company's success is a word you hear again and again if you spend time in what Exxon insiders call "the God pod," the wing of Exxon's headquarters in Irving, Texas, where Tillerson and other top execs have their offices. It's discipline, and it's apparent in everything from the company's dress code (forget casual Fridays in Irving) to its ability to cut more than 10,000 workers from its payroll since 2000, even as revenues rocketed. While Shell's (Research) project off Russia's Sakhalin Island is running months late and billions over budget, Exxon's Sakhalin venture came onstream on time and within 10% of the original cost estimate. (That project was overseen by Tillerson.) Exxon's relentless emphasis on consistency and discipline can seem forbidding to outsiders, but that's fine with Tillerson. "Simply put, it works," Tillerson told analysts in New York City in March. "The Exxon Mobil culture is something that a lot of people would like to understand better. I'm not really going to help them understand it, because it's the source of our competitive advantage." From the moment Tillerson was tapped for the top job in 2004, the oil patch has been abuzz with speculation about how he might change Exxon and whether he would strike a kinder and gentler tone than the famously gruff Raymond. The truth is that while Tillerson lacks Raymond's caustic side, it's unlikely he will tamper with a formula that has been so successful for so long. "I don't think people should look for much to be different," Tillerson told FORTUNE in response to written questions. "It's a culture that started many, many years ago. It's a culture familiar to me since I joined the company, now almost 32 years ago." A native of Wichita Falls, Texas, Tillerson graduated with a civil engineering degree from the University of Texas at Austin. He had spent summers working in construction and in steel and wasn't sure about a career in oil. But he went to work for Exxon at a natural-gas field in Katy, Texas, and as he puts it, "I've never looked back." Most of Tillerson's career at Exxon has been in the upstream end of the business—finding and developing oil and natural gas, first in Texas and later as far afield as Russia and Yemen. In the 1990s, Tillerson won notice as a skilled dealmaker when he led talks with the Russian government to develop oil and gas fields off Sakhalin Island, an area expected to contribute 250,000 barrels a day in new production by the end of 2006. "Russia was Rex's show," says Eugene Lawson, president of the U.S.–Russia Business Council, of which Tillerson is a board member. "He's got a lot of gravitas, he's physically strong, he's a rancher—and the Russians just eat that stuff up. He's the best negotiator I've ever seen." Tillerson's going to need all his negotiating skills, because the key to Exxon's growth lies in some of the world's most difficult places. Besides Russia, the company is counting on volatile Nigeria and Angola to contribute nearly one million barrels of new production by 2010. In Venezuela, where Exxon has invested hundreds of millions turning tar-sand into crude, the company finds itself in a standoff with Hugo Chávez, who has forced other companies to renegotiate their deals and pay more in royalties. But Exxon isn't budging, and if negotiations fail, it could be forced out. The biggest challenge for Tillerson will be fulfilling Exxon's promise to increase output from 4.1 million barrels a day to five million by 2010. As analyst Paul Sankey of Deutsche Bank notes, that implies production gains of 4% to 5% annually, which Exxon has fallen far short of in recent years. If Exxon can't do that, future earnings growth will depend mostly on oil prices continuing to rise—something Tillerson doesn't think likely. The Sisyphean effort to replace reserves and boost already staggering production levels is a challenge Exxon shares with other supermajors. But while Exxon's $30 billion in cash and its AAA-rated balance sheet would allow Tillerson to add reserves by buying a smaller company—as Chevron did with Unocal last year—its disciplined approach to using capital means he would rather wait until oil prices come down before doing a deal. "I'm not sure it makes sense in this environment to make a major acquisition," he says. "When I look at some of the transactions that have occurred, they seem rather pricey to me." That kind of patience has a way of paying off: Lee Raymond bought Mobil just as oil prices bottomed out in 1998. Exxon can also afford to go its own way because of its technological edge. Despite Big Oil's reputation as an old-economy industry, Exxon likes to think of itself as a technology company, pointing to systems like its brand-new Fast Drill Process that have allowed it to reduce the time it takes to drill wells by 35%, saving hundreds of millions of dollars annually. In a shabby townhouse on Capitol Hill, a few blocks from where Tillerson faced down the lions of the Senate, Exxon is drawing a different type of attention than it's accustomed to from Wall Street admirers. This is the home of Exxpose Exxon, established last year by a coalition of organizations ranging from radical Greenpeace to mainstream Sierra Club. While Big Oil has had its adversaries going back to Ida Tarbell and the muckrakers of Rockefeller's day, Exxon has always seemed to draw more fire. There are no comparable campaigns aimed at Chevron or ConocoPhillips. Exxpose Exxon director Shawnee Hoover says her group was set up to protest the company's support for drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, its skepticism about the causes of global warming, its refusal to pay $4.5 billion in punitive damages to fisherman affected by the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989, and its puny investments in alternative energy. Hoover is calling on consumers to boycott Exxon and will begin spotlighting the company's donations to political candidates. It doesn't hurt her cause that, as Hoover puts it, "no company is like Exxon—it's the stereotypical, old-school company." Representatives from U.S. Public Interest Research Group, an Exxpose Exxon backer, have enjoyed canapés and conversation with John Browne, CEO of BP, but Exxon hasn't offered Hoover or her colleagues even a cup of coffee. The closest they've come to a face-to-face meeting, says U.S. PIRG's Athan Manuel, was handing Lee Raymond a letter on Capitol Hill last year. "He groaned," says Manuel. Although it's unlikely Hoover will get an invite to Exxon headquarters anytime soon, Exxon's status as America's biggest company and its antipathy to the kind of green talk favored by BP means it will face more heat on issues like global warming. If the Democrats win control of the House or Senate this fall, the company could face a windfall-profits tax and increased regulation. "I was in business all my life," says Senator Herb Kohl (D-Wisconsin), who listened to Tillerson's testimony. "But I wish we could see a little bit more sympathy for consumers. They need to show a responsibility beyond the share price—they remind me of the tobacco industry." For its part, Exxon isn't afraid to play hardball. It has donated millions to groups like the Competitive Enterprise Institute, a Washington think tank that calls itself "a leader in the fight against the global-warming scare." Another beneficiary of Exxon's largesse: Public Interest Watch, a group that asked the IRS to audit Greenpeace, which the agency did. An Exxon spokesman says the company had nothing to do with the audit request. But there are signs of glasnost, even if Tillerson insists there is still uncertainty about the amount of temperature change attributable to emissions. He notes that Exxon has spent more than $1 billion on cogeneration at its plants to reduce CO2 emissions and has contributed $100 million to Stanford's Global Climate Energy Project. "What we support is continued efforts to understand the problem better," Tillerson says. "We need to work harder on articulating our views, and we're going to try to do better at that in the future." If America is addicted to oil, as President Bush says, Exxon's Baytown, Texas, plant is the needle. Stretching over 3,400 acres along the Gulf of Mexico, Baytown is the nation's largest refinery, turning more than 560,000 barrels of crude a day into the gasoline America craves, along with jet fuel and other petroleum products. A maze of white pipes connects the refinery to the docks where tankers unload their cargos of black gold day and night. But the most amazing thing about Baytown is the absence of people. While improvements in the plant have lifted capacity by 100,000 barrels over the last decade, the workforce has dropped by nearly a fifth. State of- the-art systems allow managers to monitor flow rates and check valves without leaving the control room. If capacity falls short of targets, they know in real time how much money is being lost, down to the dollar. Despite Exxon's reputation among greens, Baytown is remarkably clean. There are no pools of oil lying around, and it's no smellier than a gas station. "If we see stuff or smell things we don't like, it gets cleaned up right away," says technical manager, Jeff Beck. Baytown is a metaphor for Exxon itself—the ruthless drive for efficiency, the close attention to the bottom line despite record profits, and the no-nonsense attitude. It's not for everyone, but the culture has a way of getting hold of its employees and never letting go. Just outside the refinery gates at a bar called Don's Place, retired foreman Eddie Glynn Walker is nursing a beer. "I worked there 35 years, and it was tough in terms of what they expected," he says. "I miss the plant. I miss the people." Exxon may not be loved like Apple or Starbucks, and Tillerson may never win any popularity contests. But as long as Americans love cruising down the open road on a full tank of gas, Exxon is likely to remain at or near the top of the FORTUNE 500. And that's just the way the folks in the God pod like it.

REPORTER ASSOCIATE Patricia Neering FEEDBACK nschwartz@fortunemail.com FORTUNE 1000 Companies in Your State |

|