|

The Welshman, the Walkman, and the salarymen

Sony slept through the dawn of digital media. Now Sir Howard Stringer and his polyglot crew are trying to wake the company up.

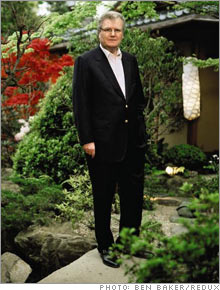

(FORTUNE Magazine) - One day last July, two naked men lowered themselves into a hot spring in Hakone, a Japanese tourist town known for its beautiful lake and views of Mount Fuji. One was a pallid, curly-haired 63-year-old Welsh-born American citizen who carries a few extra kilos on his 6-foot-3 frame. The other was a slight, balding, dark-haired 58-year-old Japanese engineer. The two men had scarcely met, but they needed to get to know each other in a hurry, so they had arranged a weekend in the country, enjoying a walk in the woods, a boat ride, and a piano concert. A big job awaited them - the task of overhauling Sony, the troubled electronics giant that had once symbolized the rise of postwar Japan.

Since then, the unlikely duo of Sir Howard Stringer and Dr. Ryoji Chubachi has rattled Sony (Research) to its foundations - cutting costs, selling assets, upending old ways. The company, which rose from the rubble of bombed-out Tokyo to delight consumers around the world with the Walkman, the Trinitron TV, the CD, and the PlayStation, needed a jolt. Sony's core electronics business has lost money for the past three years. Too many of its products lack pizzazz. Once celebrated for innovation, Sony has become an analog company in a digital world. Sony, as a result, finds itself under attack from Microsoft (Research), Samsung, Apple (Research), Sharp, Nokia (Research), Canon (Research), and Dell (Research), to name a few of its many competitors. Sir Howard, who is chairman and CEO, and Dr. Chubachi, who is president, are making every effort to inject a fighting spirit into a far-flung company that has in the past been just a little too nice. "We know that Sony is a kind, fair-minded, and intelligent company," Stringer told 1,000 company executives soon after taking over last year. "But is it a tough company? It is time to find out." This is the story of a charismatic Welshman who set out to remake a profoundly foreign corporate culture - and instill a new sense of teamwork. Since Stringer has been in the job only for a year, it's a story without an ending. But that doesn't mean it lacks for lessons. Getting started

Stringer and Chubachi began the overhaul by attacking expenses at a place with a habit of keeping executives and businesses around forever. The Aibo, a beloved robotic pet, was put to sleep. They shut down the Qualia line of boutique electronics that included a $4,000 digital camera and a $13,000 70-inch television. They eliminated 5,700 jobs and closed nine factories, including one in south Wales. (He took some flak back home for that.) They have sold $705 million worth of assets. You probably didn't know that Sony owned a chain of 1,220 cosmetics salons and the 18 Japanese outlets of the Maxim's de Paris restaurant chain. They're gone. Gone, too, is a group of salarymen in their 60s, 70s, and 80s who, after retiring from senior management positions, were given the title of "advisor," a tradition established by Sony's founders. "That was very symbolic," says Hideki (Dick) Komiyama, a Sony executive and key ally of Stringer's. The 45 advisors each had a secretary, a car and driver, and worst of all, the ability to gum up decision-making and second-guess people doing real jobs. No more. Such cost cutting is never pleasant, but it is not all that difficult either. Harder and far more important is the job that now absorbs Stringer: transforming Sony from a traditional manufacturer of standalone products into a nimble, digital creator of software, services, and content as well as devices. "Menus," Stringer says, "have displaced knobs." That, in a nutshell, is why Apple's iPod, which neatly integrates hardware, music, and an Internet platform, makes the Sony Walkman look like a tired relic of the 1970s. It's still hard to believe that Sony lost its leadership in portable music players so quickly. Sony, after all, not only invented the Walkman but also owns half of Sony BMG, the world's second-largest music company, and the whole reason that Sony bought music and movie companies many years ago was to acquire content to support its devices. The missing ingredient was software. "The bridge between content and hardware is software, and that was something we didn't master," Stringer admitted in one of a series of frank conversations with FORTUNE in New York City and Tokyo. Even now, Sony sells digital music players in Japan that are beautifully designed but so complicated to use that the company has opted not to export them to the U.S. The cultural revolution will be televised

Nothing less than a cultural revolution will be required to modernize Sony. Sir Howard needs to break down the barriers between the company's stubbornly independent business units so that people - and products - communicate easily with one another. He needs to shake up a personnel system built around seniority and jobs for life to give young people more opportunity (Sony employs about 158,000 people). He needs to get product designers to pay more heed to customers. And he needs to get all of Sony to focus on shareholder value. "In Japanese business, harmony has been more important than profitability," Stringer says. "In the past five or six years, we could go through whole board meetings with no discussion of the share price." This turnaround job won't be quick. Soon after becoming CEO, Stringer read a book by Jack Welch about how he revitalized GE in the 1980s, and one by Louis Gerstner about how he did the same at IBM in the 1990s. (He also read about the collapse of AT&T, another storied company.) Stringer was so impressed with Gerstner's book that he flew to Florida to hire him. "I have struck out the word 'IBM' and replaced it with 'Sony,' and it still reads well," Stringer told him. "You've got to help me." Gerstner has since become a mentor, encouraging Stringer to be bold. When Sony's Bravia line of liquid-crystal-display TV sets became the market leader last fall, Stringer was elated. The company had been slow to offer flat-panel sets. "We just cruised right by everybody," Stringer says. "There's so much affection for the brand, especially in the U.S., that people are almost prepared to wait to see what Sony comes up with." Gerstner took a different view. Success that comes too easily will make the job of transforming Sony more difficult, he warned Stringer. "Sony's problems go well beyond short-term business problems," Gerstner told FORTUNE. "The cultural issues, as I found at IBM, are the most fundamental, the most difficult." Complications

As Stringer got deeper into the work of fixing Sony, another complication arose. A place that had at first felt alien began to remind him of the old CBS, which was still run by its founder, William S. Paley, when Stringer went to work there in 1965. He found much to admire about Sony's culture. "Integrity is important," he says. "Quality is important." People are proud, and loyal, and they feel their work matters. Sony remains a company shaped by the values set down in its prospectus 60 years ago by Masaru Ibuka, the company's co-founder: "Purpose of incorporation: Creating an ideal workplace, free, dynamic, and joyous....We must place profit here as a secondary motive....Our service commitment shall be pure and total...." Stringer does not want to be remembered as the CEO who turned Sony into a ruthlessly Darwinian place. "You have to find a way to marry the values that Japanese business has, which are admirable, with the competitive pressures that force them to behave differently," Sir Howard explains. "How you manage and orchestrate that compromise is critical. It's something I feel every day. I can't come in and throw out the baby with the bath water in the interests of the all-American way. Nor do I want to." Why Stringer? And why Sony?

Why Howard Stringer? He does not speak Japanese. He is not an engineer. Until recently he knew little about electronics and less about software. He spent most of his career in journalism and entertainment, and flopped the first time he ventured into the technology world. A Sony employee asks Stringer that question, albeit more politely - they do everything at Sony more politely - during a town meeting of employees at a plant that makes camcorders and cameras in the Japanese city of Koda. "I didn't ask for the job," Stringer replies. "I didn't expect the job. But I feel like the company is extraordinary, and it deserves to succeed. There is so much talent, so much brilliance, so much wisdom, so much desire inside this organization. "While I don't think I have the answers, I know that you do," he goes on. "So my job is to motivate and inspire and create an atmosphere in which you do your best work." The fact is, Sony doesn't need another engineer. It needs a leader. No one has truly run the company for years. Nobuyuki Idei, the last CEO, announced restructuring plans in 1999 and again in 2003, but neither program was bold enough to really change the business. The outside world's demands

In the meantime, two big trends overwhelmed Sony. Commodification is one. Almost as soon as Sony unveils a new device, cheap knockoffs are built in China. Stop into Bic Camera, a giant retailer in downtown Tokyo, and the problem is evident: Eight floors of electronics are packed floor to ceiling with products ranging from big-screen TVs to tiny cellphones that play video. Sony's prices tend to be high. No-name brands are everywhere. DVD players sell for $25, less than many DVDs. The rise of digital media also caught Sony flat-footed. The company makes more than 1,000 products - TV sets, digital cameras, camcorders, laptop computers, the PlayStation, portable music players, VCRs, DVD players, stereos, tape recorders, clock radios, even a nursery monitor. Some interconnect, but others do not. Some use a proprietary form of digital storage called a MemoryStick, but others use generic products. Rob Wiesenthal, a top deputy to Stringer who is in charge of strategy and M&A, says, "I have 35 Sony devices at home. I have 35 battery chargers. That's all you need to know." One of Stringer's priorities is to break down the silos that isolate Sony's business units. This is a delicate undertaking. Some silos, most famously the group run by Ken Kutaragi that created the PlayStation, have been enormously successful because they operated free of Sony headquarters. Others wasted money by creating competing products; at one point, three different business units were developing their own digital music players. What's more, Stringer's discussion of silos sometimes gets lost in translation because most Japanese people have never seen one; one interpreter translated the word as "octopus pot," meaning once you get in you never get out. Eventually, Stringer did an interview for the employee magazine devoted entirely to silos, and to the theme of Sony United that he has been taking all around the world. "The Digital Age is about communications between people and devices," he said, "and there is no getting away from it." Fiscal woes in the Digital Age

The Digital Age has not been kind to Sony. In fiscal 2006, which ended March 31, Sony brought in $63.8 billion in revenues and only $1.6 billion in operating income. Electronics, which account for about 64 percent of revenues, lost $264 million. While Sony's music, games, and movie businesses were profitable, the vast majority of operating income was brought in by a financial services division, which includes a life insurance firm and a bank. Those companies are expected to be spun off in a couple of years. "It's tough to support a stock price based on the financial segment," says E. Katayama, an analyst in Tokyo with Nomura Securities. Shares of Sony have increased in value by about 28 percent since Stringer and Chubachi took over in June 2005. For the most part, that reflects the buoyant Japanese economy and stock market; the Nikkei 225 index was up by 40 percent during the same period. More revealing is the fact that Sony shares have lost 40 percent of their value during the past five years. (Maybe that's why the stock price never came up at board meetings.) Sony's market capitalization of $45 billion today is smaller than Samsung's ($98 billion), Apple's ($54 billion), or Matsushita's (Research) ($53 billion). The Sony board, led by Idei, turned to Stringer last spring because it wanted to shake things up. Sir Howard had restructured Sony's U.S. operations, which he had guided since 1997. He took out $700 million in costs and, more important, persuaded Sony's entertainment, electronics, and games units to work together. When Sony released its PlayStationPortable in the U.S. last year, the first million units were packaged with a Universal Media Disk of the "Spider-Man 2" movie released by Sony Pictures Entertainment, to underscore the idea that the game player could also be used to watch video on the go. Stringer encouraged cross-promotions (like product placements) wherever possible. In the upcoming James Bond movie, "Casino Royale," Stringer says Agent 007 "will carry so many Sony products that he won't be able to stand up." Temperamentally, Stringer bears little resemblance to confrontational CEOs like Welch or Gerstner. "I'd like to intimidate somebody once," he remarks, "but it doesn't seem likely." His preferred weapons are his British charm, his self-deprecating sense of humor, and the genuine pleasure that he seems to get from seeing others succeed. He has a knack for managing difficult people, as he did when he produced the "CBS Evening News With Dan Rather" during its heyday, and when he induced David Letterman to leave NBC for CBS. Stringer's resume

A native of Cardiff, Wales, and the son of a Royal Air Force officer, Stringer earned a BA and an MA in modern history from Oxford and immigrated to the U.S. in 1965, seeking adventure. He got more than he bargained for. After a brief stint as a writer at CBS Radio, he was drafted and sent to Vietnam. (When a Sony employee at the town meeting asks him about his medals, he is quick to say that he never fired a shot. "I have many medals because I was in charge of medals," he jokes. In fact, he received the U.S. Army Commendation Medal for meritorious achievement.) Returning to CBS, he produced documentaries and the news, ran CBS News, and eventually led all of the CBS broadcast group. He left in 1995 to run Tele-TV, a telecom startup where his best efforts failed to transform an ungainly joint venture of Bell Atlantic, NYNEX, and Pacific Telesis into a force in the television business. Two years later he took a big pay cut and a small job to join Sony Corp. of America. He was supposed to coordinate operations without actually running any of them. Soon, though, movies, music, and electronics all reported to him. In 1999, he received the title of Knight Bachelor from Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II. Tom Hanks, the star of Sony Pictures' hit movie "The Da Vinci Code," told Stringer at a promotional event that he probably knew co-star Sir Ian McKellen from "your knighthood club where you all get together, order pizzas, and talk about the Queen." As surprising as Stringer's appointment was Dr. Chubachi's. He had toiled quietly in what he calls "the hinterlands," overseeing the production of components like optical disks and batteries. Yutaka Nakagawa, another key executive on the turnaround team, was also new to the senior ranks. "If I'd met them, I'd never had a conversation with them," Stringer says. "It occurred to me that it was an unusual situation." In an interview with FORTUNE, Dr. Chubachi suggests that he and Sir Howard were chosen because they knew enough about Sony to grasp its problems but arrived in Tokyo as outsiders. "If one wishes to start a major change, a sea change, a person who stayed away from the mainstream, who is from a remote area, may be called for," Chubachi says. The two men turned out to have more in common than they knew. Both had won Emmy Awards. (Stringer collected 31 at CBS News; Chubachi won a technical Emmy for developing metallic videotape.) Both love classical music. Both enjoy baseball. At a Sony town meeting, Stringer was asked if he admired Bobby Valentine, the former manager of the New York Mets who led the Chiba Lotte Marines to their first Japanese baseball championship in 31 years. Never one to pass up a teachable moment, Yankee fan Stringer replied that like Valentine's teams, Sony has to "learn to be tough" and to "liberate the energy of young people." Engaging the Sony youth

Getting young players into starring roles at Sony is key to Stringer's reform agenda. But it isn't easy. Historically, Sony people waited a long time for top jobs. When Stringer offered a promotion to one executive, he demurred, saying, "But I'm only 48." Stringer was taken aback. "You wouldn't hear that at Google," he says. The trouble is that Sony "has a lot of people in their 50s who are not incompetent, but they are analog people in a digital world," Stringer explains. "I'm trying to figure out how to solve that. It's not something you can be cavalier about." He'd like to invigorate the company from the bottom up, not the top down. "What I've tried very hard to do is stimulate a kind of internal revolution," he says. "We've got to find ways to drill holes in the crust." Not surprisingly, Stringer and his message are being embraced more readily by middle managers than by those atop the hierarchy. "Sony United is like an airplane," he says. "The cabin class is united. The business class is getting united. It's the first class that I have the biggest problem with." He had dinner with one famous Sony engineer who told him that software was not important. Stringer has brought in a crew of aides from the West to work with Japanese insiders like Komiyama to promote change. They include Wiesenthal, a trusted dealmaker; general counsel Nicole Seligman, one of the very few high-ranking women in the company; a star software engineer named Tim Schaaff from Apple, to centralize the look and feel of Sony products; and Andrew House, a Briton who is fluent in Japanese, to be Sony's first-ever chief of global marketing. Sony's research suggests that while the brand still connotes quality, trust, and reliability, it is slipping when it comes to innovation and style, particularly among the young digerati. The digerati themselves are somewhat harsher. Randy Giusto, who is group vice president of the mobility, computing, and consumer markets at technology research firm IDC, says: "Sony used to be very Apple-like. They had a loyal following. But that's been tarnished in recent years. They haven't been able to put the puzzle pieces together of owning Sony pictures and Sony electronics and Sony games." Sony's image took a beating last fall when it was revealed that Sony BMG Music, its fifty-fifty joint venture with Bertelsmann, had surreptitiously loaded copy-protection software onto CDs that then installed itself on users' computers. The software left computers vulnerable to hackers and allowed Sony BMG to track listening habits. A class-action suit over the software was settled in May, but in the meantime technology Web sites called on readers to boycott all Sony products. Sony's electronics division has had customer-relations problems of its own. "We have this entire corps of very talented engineers, but there are times when they lose sight of customers in their ardent, devoted efforts to develop great products," Chubachi says. In the past, designers and engineers were discouraged from listening to customers; that way, they would avoid preconceptions and be free to invent great things. But the result was products like Sony's DSC-T7 digital camera, whose sophisticated technology made it the thinnest camera in the world. Customers didn't much care. They wanted technology to eliminate blurry images and take better pictures in low light. Six months later Sony came out with the DSC-T9 camera, which met those needs. "It is selling explosively, much better," Chubachi says. A new focus on great products

Stringer and Chubachi also want Sony to focus on "champion products." Some already fall into that category. The Bravia line of flat-panel TVs has won rave reviews. So have Sony's SXRD rear-projection sets. Sony's digital cameras have ranked first or second in U.S. market share in recent quarters, and its camcorders are doing well too. Sony Ericsson, a joint venture that makes camera phones and Walkman phones, shipped 51 million of the devices last year. Several new products also have Stringer excited. Sony is about to release an electronic book called the Sony Reader, which can hold dozens of books, personal documents, and Internet content; unlike prior e-books, the screen of Sony's is high contrast and can be read in direct sunlight, like a printed book. Another device, called LocationFree, can stream TV shows or movies from a TV or DVD player at home to any broadband Internet connection, for viewing on a computer screen or a PlayStationPortable. Sony's most immediate priority, though, is the launch of the Blu-ray DVD format and PlayStation 3. "Without a doubt, the most important product for them this year is the PS3," says Ross Rubin, the electronics industry analyst for the NPD Group, a market research firm. "Not only has it been a huge revenue and profit generator for them in the past, it is a Trojan horse for Blu-ray, which has big implications." The Blu-ray launch will test the power of Sony United - Stringer has thrown the weight of Sony's movie, music, electronics, and games divisions behind Blu-ray. Sony and MGM, in which it acquired a stake last year, have the largest library of color films in Hollywood, ensuring a plentiful supply of high-definition content for Blu-ray players. On May 24 in Tokyo, Stringer spoke to 1,200 Sony executives about his first year on the job and the task ahead. "Last year was spent fixing what was broken," he said. "This year we will concentrate on building for the future." He talked about Blu-ray and the PS3, of course, and about a drive for "vigorous growth" in the BRIC countries - Brazil, Russia, India, and China. He talked about breaking down the silos, as always, and about giving opportunities to talented people. But Stringer set the company's most important priority as the "conquest of software." Sony's hardware is unrivaled, he boasted, as are its movies and music. But that is not enough in the networked age. "We have to honestly admit that our capabilities remain quite modest." It will take years, he said, to make Sony a world-class software company. "We will succeed," he concluded, "because we must." It's been a grueling year for Sir Howard. He has spent more than 500 hours in the air, shuttling among New York, Los Angeles, and Tokyo, where he spends eight to ten days each month. He has taken his reform campaign to Sony outposts in Berlin, Shanghai, Beijing, and Mumbai. Only occasionally does he find his way home to the small town outside London where his wife and two children live. "I don't see my family much," he said, a bit wistfully, at a gathering of Sony employees. "My family is you." Stringer and Chubachi have come a long way since their weekend at the spa in Hakone, but their hardest work lies ahead. If they can't lead this once-great company into the digital world, then all of Sony will find itself in hot water.

FEEDBACK mgunther@fortunemail.com |

|