|

Make your nest egg last

Here's what all families need to know about making assets last so everyone can benefit.

NEW YORK (MONEY Magazine) - Even the closest families can feel uncomfortable talking about money. It's just so, well, uncomfortable. You know you should find out whether your parents have enough money to support themselves as they get older and whether they've made arrangements to pass on any assets that are left over, but you don't want to come across as nosy or, worse yet, as if you're just itching to get your hands on your inheritance.

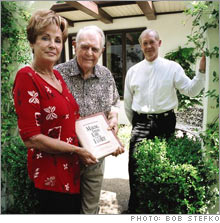

And if you're the parent of adult children, perhaps you've held off broaching the topic with your kids because you know they have their hands full with their own finances. Or maybe, to be frank, you just figure it's none of their business. Not Carrie Thomsen. The 64-year-old retiree from Hot Springs Village, Ark. doesn't believe in pussyfooting around the topic of money with her family. She has already talked with her father Dan Mabee, 89, about his will. Now she and her husband Marshall, 63, want to be sure there's no confusion among their eight children and 12 grandkids about what the couple own or who gets what after they're gone. So she has jotted down contact information and account numbers for every asset she owns in a book titled Making Things Easy for My Family. She's also listed all her jewelry, clothing and antiques, indicating who she wants to inherit what. She has even noted the music that she wants at her funeral ("Sweet, Sweet Spirit" and "Amazing Grace"). "Previous generations were reluctant to share this kind of information, but why keep it all secret?" says Thomsen. "Our kids will inherit whatever we have left anyway, so why not make it easy for them?" In fact, if you can just bring yourself to raise the subject, discussing these issues could be a lot easier than you think. In a survey last year by The Hartford, about three-quarters of parents in their seventies said they would feel very comfortable talking with their kids about the financial issues they'll face later in life, from how they want their assets divided to their funeral plans. The adult kids were up for talking too (although they weren't quite as comfortable, especially about their parents' estate). What was worrisome: The parents thought their kids knew a lot more about their financial resources and plans than the adult children actually did. That kind of miscommunication doesn't surprise Vic Preisser of the Williams Group, which counsels families about how to pass along their wealth. In a study of 3,250 affluent families, the firm found that only a third had managed to transfer the family fortune to the next generation and grow it. Lack of communication, not financial ineptitude, was the big reason. "The most important thing a family can do to successfully pass along their wealth is start a conversation," says Preisser. "Talk about your passions, your interests, what's in your hearts - and really listen to each other." Today's longer life spans make this sort of intergenerational conversation especially crucial. The first step in parents and their adult children working together as a team is making sure the parents are provided for. Here's advice for making the nest egg last. What you need to know

Keeping spending in check is key. So is managing health-care costs. The good news for today's families- that you can expect to enjoy the company of the oldest generation for far longer than has ever before been the case - also presents the greatest financial challenge. Consider: At age 65, a man now has a 50% chance of living to 85; a woman, to 88. And the odds are one in four that at least one of them will still be around at 97. That means you now have to plan for your savings to stretch 30 to 35 years or more vs. the 20 that planners used to recommend. The key is to get a realistic handle on the expenses you face, budget for them, and then keep spending in check, particularly early in your retirement. Start by projecting how much you're likely to spend on fixed expenses or bills you can't control (like housing and health care) and on discretionary items (like travel and entertainment). Whatever your initial estimate for health care is, you might need to double it: A recent survey by Fidelity found that people commonly believe a 65-year-old couple retiring today would pay about $80,000 out of pocket on health care - less than half the $200,000 that Fidelity says is likely. Then see how your vision of retirement squares with your resources - your yearly income from Social Security, pensions and withdrawals from savings. This part is critically important: Count on limiting those withdrawals to no more than 4% of your portfolio's value in the first year of retirement, then increasing that amount with inflation each year. Research has shown that this 4% rate comes close to assuring you won't run out of money before you run out of time. If you can't support your lifestyle on just 4% and you aren't willing or able to do part-time work to supplement your income, go back to the discretionary part of your budget and look for places to cut back. How to start the conversation

For adult children, the goal is to help your parents create a sound spending plan without appearing intrusive. Maybe you start by showing them an article or a brochure from a financial services company about how to make your money last in retirement. Or you talk to them about some aspect of your own retirement planning. Both backdoor approaches can lead naturally to further questions and discussion that will help you determine if your parents can really afford their lifestyle. Make sure you ask about your parents' wishes regarding medical care. Among the critical questions: If you get sick, is it important to you to receive care at home for as long as possible? How would you feel about moving to a retirement community that has on-site medical care? The answers will help guide a discussion about how to pay for it. Besides simply dipping into savings to pay for care, there are two basic choices: Buy long-term-care insurance, which covers the cost of a nursing home, an assisted-living facility and, often, home care. Or buy into a continuing-care retirement community (CCRC), which offers on-site health care and a range of housing choices, from independent living to assisted living to nursing-home care. The idea is that you can move from one arrangement to another as your medical needs dictate. Neither is cheap. A long-term-care policy for a 60-year-old couple might cost from $1,500 to $4,000 a year, depending on how long a nursing-home stay is covered and whether the policy's payments rise with inflation. With a CCRC, there's an entrance fee ranging from $100,000 to more than $500,000, and monthly fees, typically about $3,000 - although much of these costs might be covered by the sale of an existing home. For Hildy, 76, and Van Gathany, 80, the choice was to move into Lake Forest Place, a CCRC in Lake Forest, Ill. with a fitness center, on-site medical facilities and restaurant-quality dining. Both of them had parents who happily lived in similar communities. Remembering the sense of relief they felt seeing that their parents were well cared for as they aged, Hildy and Van wanted the same for their own children. "We thought it would be a big load off our kids' minds knowing that we'll always be taken care of here," says Hildy. _____________________________

|

|