A stadium name bubble?The wave of corporate naming-rights deals for sports venues has some scratching their heads. But teams are raking in record cash.NEW YORK (CNNMoney.com) -- Corporations have developed an edifice complex once again. Companies are rushing to pay top dollar to put their names on new stadiums and arenas. Three deals in the New York area alone have been announced in the past few months with the sponsorship dollars totaling nearly $1 billion. And potentially the biggest deal, naming rights for the new shared home of New York's Giants and Jets football teams, is yet to come.

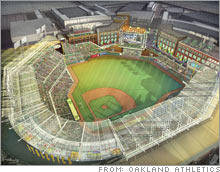

The latest deal was announced Thursday. British banking giant Barclays PLC (Charts) agreed to pay a reported $400 million for a 20-year deal for the new basketball arena in Brooklyn (the future home of the New Jersey Nets), even though Barclays is not a player in the retail banking market in New York City. Across the country two tech heavyweights - business software provider Oracle (Charts) and network equipment provider Cisco Systems (Charts) - have waded into the naming game, even though their sales are mainly to IT professionals, not the general public. Oracle already has its name on a basketball arena and Cisco will have its name on a new baseball stadium. Those involved in naming-rights fields negotiations say the deals make sense, even for the sponsors without a broad customer base. "When you look at the brand in the market, these deals are occurring because they want to be seen as leaders in their space" said Bill Glenn, vice president of insights and analytics for The Marketing Arm. Still, some seem more confusing or jarring than anything else. Both the Fiesta Bowl and college football's national championship game were played earlier this month at the University of Phoenix Stadium. But this new stadium is the home of the NFL's Arizona Cardinals, not some phantom Division I college team. The University of Phoenix is a for-profit national college that doesn't even have a football team. It paid $66 million to have its name on the stadium for the next 30 years. Dean Bonham, who has helped negotiate dozens of these agreements, including the Oracle deal, agrees that the University of Phoenix deal seems a bit confusing. But he said other sponsors without a broad customer base may have their eye on the future when they might be selling more directly to the public. "Those deals are more a statement about the future of those companies than they are about where they are in marketing today," said Bonham. "Barclays is making a statement they're going to become more of a player in the financial center of the world. It's not going to be surprising if they go out and buy a financial institution that has more consumer focus." Both Bonham and Glenn said they believe the Giants-Jets stadium is poised to reach record dollar levels. But one other source in the industry said the firm handling the negotiations is telling National Football League teams not to necessarily expect the $25 million a year that some people are forecasting. No corporate name for new Yankee Stadium The planned stadium that has perhaps the greatest naming rights potential is the new Yankee Stadium now under construction across the street from the existing park. But while fans can expect to see various gates, concourses and banks of seats, such as the bleachers, carrying sponsors' names, one executive involved in the planning of the stadium insists that the team will not put a corporate name on the park itself. The Yankees have learned that building their fans' affection for the team's history and tradition is a powerful marketing tool that has helped them improve revenue. But not having a sponsor's name on the new park probably does mean the team is leaving hundreds of millions of dollars on the table. "This really is a bow to tradition," said the executive, who spoke on the condition that his name not be used. "There's no market study that says if you change the name you reduce the value of the Yankees' brand." Bonham said that lots of times there's a backlash by fans against a corporate sponsor on a new park. He worked on the deal for Invesco Field, the Denver Bronco's home that opened in 2001. Fans were originally upset about the use of a corporate name for the stadium, but Bonham said by the start of the next season the controversy had disappeared. But he and Glenn said the Yankees probably would have faced greater prolonged fan backlash than any other team if they had sold the name of the new park. "The emotional attachment that fans have to the Yankee Stadium brand is unlike anything else," said Glenn. But even if the Yankees steer clear of a corporate sponsor for their new stadium, this is still a boom time for naming- rights deals. According to trade publication Street & Smith's Sports Business Journal, 2006 was the most active year since 1999 for new naming-rights deals. Several of the most expensive deals ever were signed in 2006 as well - with the $400 million, 20-year deal by Citigroup (Charts) to name the New York Mets' new baseball stadium CitiField topping the list. The average annual value for the 12 deals that were signed last year or first took effect in 2006 is $5.25 million, 61 percent above the average value of the new stadium rights deals from 1999. Still in some ways these deals have the smell of the late 1990's dot.com naming-rights bubble, when new stadiums and arenas were financed with the largess of companies like energy trader Enron and Internet venture capital firm CMGI (Charts), which also had customers who were also not the average Joe Fan. CMGI had to pull the plug on its sponsorship of the Patriots' football stadium before the first game was played there due to financial problems. We all know what happened to Enron. At one point this column was a careful tracker of what I called the stadium sponsor curse, which seemed to predict bankruptcy or at least plunging stock prices market-trailing stock performance for the companies with the hubris to sign naming-rights deals. But by 2003 the curse was sputtering and it seemed to die in 2004, with the sponsors' stocks outperforming the broader market. Even Delta's 2005 bankruptcy didn't seem to bring it back. And the latest figures appear to have driven a stake through the heart of the curse. The 65 companies with listed U.S. shares and naming-rights deals saw better than 16 percent gains in stock value as a group last year, better than the nearly 14 percent rise in the broader S&P 500. Still, it's important to remember that in 1999 those earlier stadium and arena deals all looked like they made sense as well. Enron was seen as strong as any company in America. Maybe the curse isn't dead - it's only in hibernation. The Kentucky Derby, brought to you by.... |

| |||||||||