The neutron bomb of health insuranceImagine being insured...and then not being insured. Such situations are on the rise.(Money Magazine) -- Waiting for an overdue reimbursement check is a hassle. Finding that your health insurance has been nullified after you've incurred serious medical costs can be an outright catastrophe. Called "rescissions," such ex-post policy denials are rare - insurers say they affect only about 1 percent of individual policyholders (they don't occur in employer-sponsored group plans) - but the practice appears to be growing.

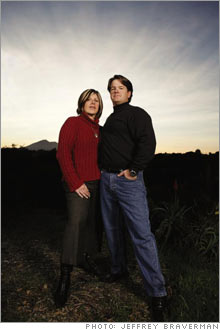

Last year, for example, California regulators launched investigations into the rescission practices of Blue Shield, Health Net, PacifiCare and other providers. Meanwhile, the Connecticut Department of Insurance is also investigating Assurant Health after 15 of 20 complaints to the state attorney general involved its use of retroactive denials of coverage. (Assurant asserts that it enacts rescissions only when policyholders don't provide truthful or complete information during enrollment.) Rescission is, in effect, the neutron bomb of health insurance. If you're hit by one, you're not only left without insurance to cover the illness at hand, but you're also liable for your previously paid claims. In some states, insurers can't void your policy unless they can show you meant to deceive them; in others, including Michigan and Ohio, they can drop the bomb over any inaccuracy, even an innocent mistake. "This is a very serious concern," says Cindy Ehnes, director of California's Department ofManaged Health Care. "The consequences of failing to list something as simple as headaches can be profound." Consider Barbara and Don Saxby of San Rafael, Calif., a self-employed couple who applied for an individual health insurance policy with Nationwide in January 2006. When Barbara showed the application she'd submitted to Don, he pointed out a couple of gaps in his medical history. Barbara called Nationwide to correct the application, but was told not to worry, the insurer would catch omissions during underwriting. Shortly after the policy went into effect, Don, 41, tore most of the ligaments in his left knee in a skiing accident. The ensuing surgery was unusually expensive, partly due to a condition in which Don's blood doesn't clot normally. (The blood condition was on record with his doctors, who didn't consider it a problem. Nor had it stopped Don from qualifying for insurance in the past.) In December, Nationwide sent a letter rescinding Don's policy due to a "misrepresentation" on the application. The Saxbys now find themselves saddled with more than $400,000 in medical bills and are pursuing litigation against Nationwide. "This just isn't right," says Barbara. "They don't even bother to do due diligence." (Nationwide declined to comment on the case.) For many applicants, the trouble starts when they sign a medical release giving insurers access to their medical records. Don't assume the insurer is going to examine those records before okaying coverage. It may not follow through, says Paul Roller, a former insurance commissioner of Alaska who's now a plaintiffs lawyer in California. "The company takes the position, 'We have a clean application so there's no need to get records,' " he says. "The insurer, in effect, says, 'If I know about a condition and you get sick, I'll have to pay. So don't tell me.'" The period of convenient ignorance ends, of course, as soon as you file a claim. Many insurers use software that singles out claims for review by diagnostic code. The review then determines if you may have had a pre-existing condition or left anything off the initial application. While insurers need to protect themselves from people who misrepresent their health status to get coverage, the potential for abuse is obvious: An insurer looking to lower risk can use the review to find any excuse not to pay an expensive claim. Says Connecticut Attorney General Richard Blumenthal: "There is powerful evidence that 'look back' provisions are used systematically to exclude people with valid claims simply because those claims are expensive." How to protect yourself So what should you do if your health policy is rescinded? File an appeal with your insurer right away. And if the company sends you a check refunding your premiums, don't cash it. That can be taken as tacit agreement, says Bryan Liang, executive director of the Institute of Health Law Studies at California Western School of Law in San Diego. If you lose the appeal, file a complaint with your state. If all else fails, consider hiring an attorney. Meanwhile, shop for a new policy. If you live in a state like Massachusetts, where insurers are required to offer you coverage, you'll likely pay more, but at least you'll be insured. In states like California, which allows insurers to refuse to sell a policy to anyone with a previous medical condition, you may be relegated to your state's high-risk insurance pool. Obviously it's better to try to avoid rescission from the get-go. When filling out an application for a policy, err on the side of telling too much, noting any condition you've ever been seen or treated for. And if you've been with a health plan for two years or more, be cautious about switching carriers. Rescissions are typically allowed only within the first two years of a policy. Liang, for one, sees practices like rescission and lowballing as a sign that insurers - property and casualty companies as well as health carriers - sometimes forget the business they're in: buying risk. "Risk means you win some, you lose some - you can't eliminate it," he says. "That's not what insurance is about." The best insurers know that. But to assume yours is one of them may be taking on more risk than you should. _______________________ More from the Money Magazine special report: Improve your odds of getting the policy benefits you expected |

|