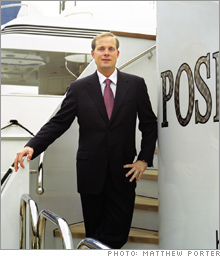

The investors: How to get rich trading "idiot" loansInvestors have made a fortune trading bonds backed by mortgages.(Money Magazine) -- The housing boom was good to John Devaney. Really good. He owns a Rolls-Royce, a Gulfstream Jet, a 12,000-square-foot mansion in Key Biscayne and a 143-foot yacht, as well as a few Renoirs and a valuable 1823 reproduction of the Declaration of Independence. Devaney's not a developer, and he's certainly not a flipper. The 36-year-old CEO of United Capital Markets is a bond trader. And one of his specialties is buying and selling bonds that are backed by the mortgage payments of ordinary homeowners.

Home Affordability

Option ARMs? Devaney loves 'em. "The consumer has to be an idiot to take on those loans," he says. "But it has been one of our best-performing investments." Devaney's not out to get people into bad loans - or into good ones. He just makes bets on how many people will repay and when. Still, the $5.7 trillion mortgage-backed-securities market had a key role in today's housing mess. "The broker and the lender and everybody else in between is part of a factory that's producing bond securities for Wall Street," said attorney and consumer advocate Irv Acklesberg in testimony before a Senate committee recently. On the other hand, the fact that Devaney and other investors are willing to own mortgages may also be one of the reasons you could afford your house. Banks have been selling off their mortgages to the bond market since the 1970s. Bond investors get the borrowers' monthly payments and the promise that they will be paid back, while banks get immediate cash and the chance to unload some risk. All this makes it easier for them to make new loans - good news for most borrowers. The trouble is, Wall Street's rocket scientists keep finding more sophisticated ways to repackage and resell mortgages. As a result, lenders stopped worrying so much about credit standards and learned to love risky loans. Look, for example, at the financial Frankenstein's monster known as the collateralized debt obligation, or CDO. Brought to life in the 1990s, the CDO helped solve a knotty problem for lenders. They were often left holding a small amount of loans that were too dodgy to sell to investors at an attractive price. But what if you grouped the payments from all those risky mortgages together, along with some other investments, and you sold some investors the right to be the first ones to get paid? This would look like a relatively safe investment, and so - voilà! - you've transformed a risky loan into a triple-A rated security. Other investors would be farther back in line and might not get paid if things went badly. But you could offer those investors very high yields, so that hedge funds and pension funds would roll the dice. This set the whole mortgage-bond sector on fire. Banks rushed to make mortgages - any kind of mortgages. Lousy credit? No problem. Can't prove your income? No problem. Can't pay more than 1 percent now? No problem. Now a lot of that lending looks foolish. Mortgage delinquencies among so-called subprime borrowers have risen to 13 percent, the highest in at least 10 years. The market for the lowest-credit-quality mortgage bonds has tanked. And investors in CDOs may be in for a rude shock. "Some of the investors who bought CDOs certainly took on more risk than they thought," says John Weicher, a former assistant secretary of housing now at the Hudson Institute. But Devaney, who told a crowd of investors that the riskiest mortgage bonds looked "awful" before the crash, says he thinks he'll be buying. "I don't believe the carnage and fallout will be as bad as people think," he says. Whether or not big investors come out okay, the damage is done for many homeowners. "The system allowed banks to create unsustainable loans that are going to haunt borrowers for years to come," says Allen Fishbein, director of credit and housing policy at the Consumer Federation of America. "Unlike the bank, the borrower has no way to lay off the risk." What comes next? The pullback. Investors will be more selective about where they put their money, and banks will be more cautious in their lending. That's basically healthy. But the risk is that this will happen so fast that we'll see a vicious circle develop: Falling home prices mean less credit, and less credit means fewer buyers and, hence, falling home prices. That could make a housing recovery that much harder to come by. |

| |||||||||