A greener smokestack?Chemical company Fuel Tech prospers by cleaning up coal utilities.(FSB Magazine) -- Making electricity is a dirty business. Just take a peek inside the boiler at your typical power plant. Fueled by crushed coal, a fireball howls and burns at 2,500� Fahrenheit, hot enough to melt iron. A ghostly snow of ash drifts down around the fire until it hits a pipe or a ridge. There it piles up, melts and hardens into slag, which reduces the boiler's efficiency. Removing the slag is costly, time consuming, and dangerous. Slag formations can grow to the size of a small car and weigh several tons. Some workers have used shotguns to try to blast the stuff off the boiler; others have used jackhammers. Neither method works very well. For decades, slag has been the nightmare of the utility industry. All of which explains why the stock market is excited about a small company called Fuel Tech (fuel-tech.com), No. 12 on the FSB 100. With the help of sophisticated computer imagery, Fuel Tech injects a chemical cocktail into boilers that helps reduce slag, curb emissions and boost efficiency.

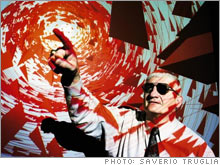

To date, 30 coal-fired utilities in the U.S. and Europe have installed the technology. Meanwhile, power plants in China and other developing countries are considering Fuel Tech as they face international pressure to reduce pollution. Fuel Tech's (Charts) revenues soared 42 percent, to $75 million, last year, and net income topped $6.8 million. The stock has tripled in the past year to about $30. Ten years ago Fuel Tech was losing millions making air-pollution-control equipment for paper mills and other big manufacturers. That market was in the doldrums, hobbled while industry executives and federal regulators fought over emission standards in the courts. At that time Fuel Tech was owned in part by NALCO (Charts), a water-treatment company in Naperville, Ill. NALCO was eager to unload the struggling unit. In 1998 a retired oil and chemical executive named Ralph Bailey paid $3.5 million for a 22 percent stake in Fuel Tech and became a hands-on investor. Bailey, 83, is no stranger to heavy industry. He was CEO of Conoco (Charts, Fortune 500) and later served as vice chairman of DuPont (Charts, Fortune 500), the chemical giant. When he first bought into Fuel Tech, Bailey predicted that U.S. industry would soon face heightened pressure to clean up its act. He also believed that the next energy crisis would force the nation's power producers to squeeze more megawatts from every lump of coal. "Fuel Tech had spent a tremendous amount of time and money to develop its technologies in the 1980s and 1990s," Bailey said in an interview. "When the market heated up - bingo! We were ready to go." Bailey's new management team revved up marketing to focus on utilities in the U.S. Half of the nation's power comes from coal, which is relatively cheap and plentiful. (U.S. mines hold vast reserves that won't be tapped out for centuries.) But coal is a filthy fuel that emits mercury, sulfur dioxide and CO2, a major greenhouse gas. Federal pollution regulations are strict and are likely to become stricter during the next few years. That means the nation's 1,500 coal-burning plants will need to curb their emissions even more. Faced with pressure to keep electricity rates down, utility executives are seeking low-cost solutions. Enter Fuel Tech, which developed a proprietary method in which workers insert nozzles into a boiler and spray a compound similar to milk of magnesia into the fire. This makes the boiler's ash residue less likely to stick, thus reducing slag. Fuel Tech's competitive edge? It uses a computerized model of the fire to know exactly where to spray the compound. In the past year or so Fuel Tech has been pushing its technology into the global market. Demand for power is soaring in the fast-growing economies of China, India and Mexico. Experts predict that China, which is opening the equivalent of two coal-fired plants a week, will double its coal consumption within ten years, to three billion tons a year. (By contrast, the U.S. uses slightly more than a billion tons of coal a year.) But Fuel Tech's slag system is new technology, and the firm's biggest challenge is to sell utility executives, who are notoriously slow to change. Also, its biggest competitor is GE (Charts, Fortune 500), which is no slouch. So last year Bailey, avoiding a mistake often made by fast-growing small businesses, reached outside and hired a seasoned chief executive with deep industry knowledge. John Norris, 58, formerly ran Duke Engineering & Services, a unit of utility giant Duke Energy (Charts, Fortune 500) of Charlotte. During his tenure, Norris built the unit into an engineering powerhouse with a global clientele. Norris is winning converts by offering utility executives a no-risk trial of its slag-removal technology. Jimmy Blakley was struggling with costly slag problems at the Western Farmer's Electric Coop plant that he helps manage in Paris, Texas. Shutting down the boiler to manually clean out the slag cost $800,000 a day, for as many as ten days every year. Blakley balked when he first heard about Fuel Tech. "I told them folks nobody's drilling any holes in my boiler, and nobody's spraying any chemicals in there either!" he recalls. But Blakley relented when Fuel Tech offered its no-risk demonstration. Today, he says, the coop pays Fuel Tech $1 million a year but saves $4.5 million annually in maintenance costs while reducing emissions by 10 percent and boosting power production by 5 percent. "We've only scratched the surface," says Bailey. "There's a global market ready to pay for what we can deliver." And he's already reaping the rewards. His original stake - bought for $3.5 million in 1998 - is now worth $150 million. |

Sponsors

| ||||||||||||