NFL's ugly body blowsThe uproar over injured and disabled former NFL players not getting the medical help they need is giving the most profitable sport a black eye.NEW YORK (CNNMoney.com) -- The National Football League is generally a flawless marketing powerhouse. But a bunch of broken-down, retired players are in the process of handing the NFL its biggest public relations loss in years. The players are starting to demand more help from the multi-billion dollar league for serious injuries that have left many of them in constant pain and unable to work, but also unable to get assistance from the pension and disability fund that is set up to help them.

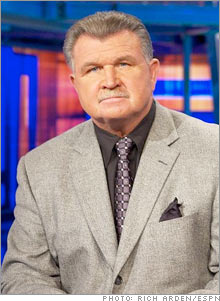

On June 26, a group of critics, led by former coach and player Mike Ditka, will appear before a subcommittee of the House Judiciary Committee to look into charges that the pension fund, administered by the league and union, is improperly denying benefits to the former stars who sacrificed their long-term health to help make the NFL the nation's most popular and profitable sport. Ditka can be the NFL's worst nightmare. A high profile figure who epitomizes the league's macho tough guy image, the Hall of Fame player and coach is able to get publicity whenever he wants to. He and some other Hall of Fame greats, such as former Buffalo Bill Joe DeLamielleure, have joined together to form a group called "Gridiron Greats." The group has raised $400,000 since February to give to the injured and destitute former players and is pressuring the league and the union to make changes. It is accepting donations at gridirongreats.org. "[Football's] a fantastic game but it's become an ugly business because some people have gotten greedy," DeLamielleure told me Friday. "There are a lot of older fans who are fed up with it." But raising money privately is not a solution. Setting aside an additional 1 percent of league revenue would more than quadruple the amount that could be paid out to in injured and disabled former players. A $5 per ticket surcharge would raise even more. DeLamielleure said he's not certain how much it would take to take care of everyone who needs help. "We've had way more response than we ever imagined," he said about his group's efforts. "There are a lot of guys hurting out there that we never knew about." But the league is answering the charges with the kind of tone-deaf response normally associated with Major League Baseball, not the image-conscious NFL. The NFL points to the 284 players receiving disability payments totaling $19 million last year, but that only comes to a modest average of $66,000 each, hardly sufficient for some of the players facing severe and costly medical problems. And many of the retired players are not even seeing that level of help. Ditka and his group are highlighting the cases of those who got nothing but runarounds, stonewalls and denials. The health and financial problems have even led to suicide and homelessness for some former stars. NFL spokesman Greg Aiello said that Dennis Curran, the league's attorney who administers various benefit plans, would be the one testifying on behalf of the NFL as he is the most knowledgeable on the topic. But even a public relations klutz like Baseball Commissioner Bud Selig knows enough to show up on Capitol Hill himself when his sport is under fire. Aiello initially wouldn't comment when I asked him if the league was worried about having its image damaged by the attention given to the problems of former players. He then called back to say, "If people know the facts, they will see we're doing a great deal for retired players, and we're in the process of discussing the other ways to address the medical needs of retired players." What he's referring to is an announcement by the league and the NFL Players Association last month to form an alliance to better coordinate getting medical assistance to retired players. But the program did not include any additional money or changes in guidelines for who would be eligible for assistance. So far most of the negative attention has been focused on the union, rather than the league, perhaps because while the league has been callous, union officials have been downright belligerent in the face of criticism. Union chief Gene Upshaw told the Philadelphia Daily News he'd like to break DeLamielleure's "damn neck." And when questioned about the retirees, Upshaw once responded that it's the current players, not the retired players, who elect him, which only serves to make his membership seem greedy and heartless. Even if that's true, Upshaw's not doing his membership any favors by painting them that way. "We look forward to next week's hearing to discuss the improvements and advancements made by the NFLPA in the area of retired players' benefits," is all the union said in a statement when I asked about the hearing. But even if the union is the one looking worse in the current fight, the NFL is damaging its brand by not moving quickly to fill the needs of the former players who are suffering. Instead, the publicity about their problems, and the hearings next week, are making fans think about the dark side to the hits and excitement they enjoy every Sunday. Whether or not this translates into lower television rights fees or ticket sales going forward, the NFL is usually smart enough to recognize when it is hurting the value of its gold-plated brand. For a league that jealously protects is image in all other instances, its response is not only bad policy on a humanitarian basis. It's surprisingly bad business. |

| |||||||