The many faces of Ralph LaurenAmerica's billion-dollar designer is going global and upscale while creating a new in-house brand for J.C. Penney. Can he really sell all things to all people?(Fortune Magazine) -- Ralph Lauren was doing reconnaissance, lingering outside one of his stores watching customers. On this crisp fall Saturday afternoon a few years ago, he had driven one of his vintage cars from his estate in Katonah, N.Y., through the leafy back roads of Westchester County to the nearby town of New Canaan, Conn. At the store Lauren made an observation that would add a new chapter to his legacy. The mothers were leaving with shopping bags, he noticed, but the daughters were exiting either empty-handed or with just a shirt for their dad or boyfriend.

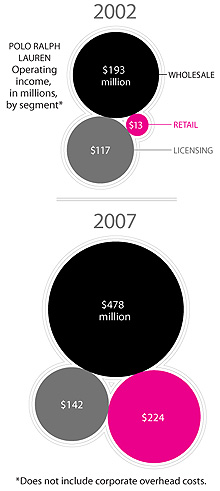

As Lauren stared at this demographic segment that had evaded his $4 billion fashion empire, he had a feeling that reminded him of the character played by Steve McQueen in "The Thomas Crown Affair". In that 1968 movie, McQueen portrays a polo-playing Boston Brahmin who is no longer challenged by running his conglomerate, so he masterminds the perfect bank heist. Lauren loves the line that comes after Crown has spent the day on Cape Cod putting a dune buggy through its paces (and the night with Faye Dunaway's character). As Crown enjoys a cigar, he bets his love interest that he can't be caught. "I did it once. I can do it again," he says. So Lauren was inspired to develop a completely new brand of clothing, named Rugby, to be sold through its own retail spaces, which look like a combination of Hogwarts and a Harvard final club. "I felt we were not connecting as much to young people from 14 to 29, so I created Rugby, which is more irreverent and schoolboy in feel than Polo," he told Fortune. Lauren quietly opened the first Rugby store in 2004 on Boston's Newbury Street, stocked with an inventory whose connection with him is betrayed only by the initials RL (price for the basic Rugby shirt: $68). Rather than heavily advertise the nascent brand, Lauren let word of mouth build it. Nine stores have been opened in places ranging from Palo Alto to New York City's Greenwich Village, with several more coming. This is classic Ralph Lauren. Not just the clothes, but the man. Anyone who assumed the Polo founder was a one-trick pony, a billionaire satisfied to license away his famous name and retire to his string of estates from Telluride, Colo., to Round Hill, Jamaica, doesn't know what makes Ralph run. At 67, after 40 years in business, he is just getting started with his latest plan: making his name into an immortal brand, known to billions around the world. In February, J.C. Penney (Charts, Fortune 500) will debut American Living, a new, moderately priced apparel and home-furnishings line that Lauren's company has created for the resurgent department store chain. Simultaneously, Polo Ralph Lauren Corp., as his company is called, has been going further upscale and farther afield, evolving its business model from a domestic apparel maker to a global luxury brand with the hope of seeing a third of its business come from Asia and another third from Europe in the next decade (double its current positions). Launching a line for J.C. Penney while opening luxurious flagship stores in Tokyo and Moscow could create an identity crisis for even the most seasoned marketer. But Lauren's gift is his ability to invite consumers into his aspirational world, whether they enter it through a $14,000 alligator handbag named after his wife, Ricky, or a Chaps polo shirt ($19.75 at your local Kohl's (Charts, Fortune 500) department store). "Polo has taken an unusual path to luxury," says Liz Dunn, a retail analyst at Thomas Weisel Partners. "They didn't start with $3,000 ball gowns. Most luxury-goods companies start at the high end, and then they filter their brand downstream and do diffusion lines, which they look at as a necessary evil. But Ralph Lauren strives to be excellent at every price point. They are maniacal in their focus on every category." Maniacal focus has had a lot to do with Lauren's ability to control his own destiny at a scale where other famous designers have faltered. Polo Ralph Lauren has $4 billion in revenue and a market cap of over $8 billion. With more than 14,000 employees and stores in 65 countries, Polo is bigger than household names like Tiffany and Saks. Among the great designers - American heavyweight division - he is the last man standing. Calvin Klein cashed out in 2003, and Tommy Hilfiger is now private equity's captive. When Lauren (pronounced like Lauren Bacall, not like Sophia Loren) looks in the mirror, however, he doesn't see merely a designer. He sees himself as a visionary who hopes to leave behind an iconic American company as his legacy. In one of several interviews for this story, Lauren explained to Fortune what drives him these days: "Bill Paley had a vision for CBS. He had clarity. He had a dream. He had talent. He had a focus, and he believed in that vision, and his company ended up having longevity." At first, it sounds like braggadocio. William S. Paley ... Ralph Lauren? (Come on, "Lauren" isn't even his real name.) But in his own way, Ralph Lauren (the former Ralph Lifshitz from the Bronx) has created as sterling an American brand as the Tiffany Network. His ad campaigns promise entr�e to a primetime lineup of tycoons, debutantes, cowboys, and big-game hunters. The price of admission? Just buy his clothes. Being added to the S&P 500 index, as Polo's (Charts) stock was last February, would have been a stretch a decade ago. Back in 1997 the newly public company (ticker symbol: RL) was reeling from a double whammy. The Ralph Lauren name and the pony logo were appearing on too much low-end product, debasing the company's cachet. (Ralph would later describe this moment to a colleague as a time when Polo was "resting on its Laurens.") The stock was in the doldrums too. So the designer went out and hired a murderer's row of fashion and finance executives, who helped him transform Polo Ralph Lauren from a company that relied on licensing, department store sales, and factory outlets to one with a growing luxury retail business. And how they evolved the company's business model while rebuilding its brand is an instructive tale for anyone who seeks to profit at the intersection of art and commerce. The secret of Ralph Lauren 's success is his unique skill set. To call Lauren a designer would be only partly accurate, for he also thinks like a brand manager, a merchant, and a customer. He doesn't sketch and never attended fashion school. Instead, when he "designs," he acts more like a filmmaker. He sees the movie for his collections in his head, and he tells his design team the narrative for which they're expected to create costumes. |

Sponsors

| |||||||||||||||||||