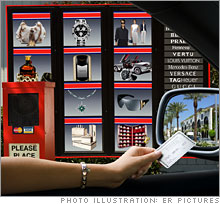

Luxury goes mass marketCall it the age of McLuxury. The $220 billion global industry is racing to the top and the bottom at the same time. But can the world's most exclusive brands stretch that much and still keep their cachet?(Fortune Magazine) -- The next time you're waiting for your bags to arrive at O'Hare, ponder this: In Milan there's a leather goods store called Valextra, just down the road from the famed La Scala opera house, whose signature product is a line of exquisite luggage quite unsuited to modern life. The suitcases, which start at about $5,000 apiece, have no wheels, no pull straps, no retractable handles. Most striking of all, they come in gorgeous white leather with a subtle creamy hue that would scuff instantly if checked onto a commercial airline. As Valextra sales assistant Martina Terazzi discreetly points out, they are best suited for people who travel by private jet.

This is what "luxury" used to mean: beautifully crafted, hideously expensive, and unashamedly elitist. Owning such items was not just a question of wealth; it was also a question of class. Luxury goods were sold in stuffy stores with intimidating personnel in white gloves who glanced at your shoes before deigning to show you their merchandise. Today that's the exception. For the most part, luxury is no longer reserved for the spoiled rich. Increasingly it is the domain of the global middle class on an ego trip - people from Indiana to India prepared to pay a premium for the thrill of owning something that makes them feel special. Luxury houses like Dior, Cartier, and Chanel have made fortunes by extending their product lines to cater to such aspirations. And we're not just talking about the traditional accessories. Armani sells chocolates. Prada has a cellphone. "We are not in the business of selling handbags. We are in the business of selling dreams," says Robert Polet, chief executive of the Gucci Group. (And at Gucci those dreams can come true for as little as $80 - the price of a box of playing cards.) Although stock prices have taken a hit in recent weeks, luxury sales have boomed along with the global economy. The world market has doubled in the past decade to about $220 billion a year in retail value. That has encouraged many companies with less pedigree to try to muscle their way in. They call themselves purveyors of "accessible luxury" and claim to be both classy and good value. Coach (Charts) is a prime example.Starting in the mid-1990s, CEO Lew Frankfort repositioned the stodgy leather-goods firm as a less expensive Louis Vuitton and watched its $300 bags fly off the shelves. Mass marketers are getting in on the act too. H&M first teamed up with Karl Lagerfeld in 2004 and now works regularly with big-name designers. Target (Charts, Fortune 500) deals with Mossimo Giannulli and Isaac Mizrahi. Through these partnerships, says Target VP Trish Adams, "our guests have learned - and come to expect - that high fashion doesn't have to mean high prices." This jostling for position raises a fundamental question: What does luxury mean if everybody claims to be doing it? "It has become one of the most overused words in the English language," sniffs Simon Cooper, president of Ritz-Carlton, the hotel chain once synonymous with a gilded existence and now slugging it out with a host of competitors. "You can't find an ad even for the cheapest car that doesn't have the word 'luxury' in it." The question applies equally to the high and the low end. It's easy to understand that a $220,000 Louis Vuitton Tambour Tourbillon gold watch is a luxury item, but can the same be said of $275 Vuitton sunglasses? Is a Stella McCartney collection designed for H&M any different in status from Stella McCartney's collections for her own brand, which is part of the Gucci Group? Wall Street's answer: Relax. Luxury has become one giant pyramid, it reckons, with brands like Cartier and Vuitton at the top and Coach near the bottom. From its perspective, anywhere in this pyramid is a great place to be, since luxury firms trade at a premium, and industry analysts predict that the market will keep growing at an annual clip of 8% to 10%. Yet within the sector itself, there's furious resistance to the notion of lumping everyone together. Louis Vuitton chief executive Yves Carcelle is scornful of the idea that most of the others in the pyramid are even competitors. "The confusion does not exist," he says. "Consumers are much more intelligent than one imagines. There are just a limited number of houses that respect the rules of luxury." By that he means predominantly old-line European firms with time-honored traditions, the highest standards of craftsmanship, innovative design, and a selective distribution policy that usually includes a network of wholly owned stores and strict controls on licensing, discounting, and anything else that could hurt a brand's reputation. Peter Marino, who designs those costly Vuitton stores, argues that the whole point of luxury is that it isn't accessible to everyone. "Coach has nothing to do with luxury," he says. "It could be selling iron ore, but it just happens to sell handbags. This is not about girls in China with a sewing machine, but about workmanship, exclusivity, and the sheer gloriousness of the materials." At Gucci, Polet plays down Stella McCartney's 2005 collection for H&M. "It was just a one-off that reinforced the global scale and importance of the brand," he says. The accessible-luxury crowd is equally adamant. Mizrahi decries critics of his work with Target as "brand racists" and says "it's nearly impossible to be luxurious without mixing it up and keeping it real." At Coach, CEO Frankfort concurs. "When did they last speak to a consumer?" he asks of his detractors. "Luxury has been democratized." As for quality, Frankfort insists that Coach bags "are as well made as products anywhere. We even source from some of the same tanneries as European houses. But because we manufacture in low-cost countries, we can pass the savings on to consumers." |

Sponsors

| |||||||||||||||||