Blind-siding college football starsMichael Oher and other top juniors have to a make life-changing decision about whether to stay in college without knowing all the facts. That's wrong.NEW YORK (CNNMoney.com) -- Michael Oher likely has only 120 minutes left in his college football career. And strangely enough, fans of University of Mississippi football, where he now plays, have NCAA rules that are designed to keep football players in college to thank for his departure.

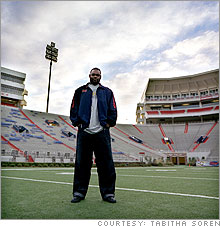

Oher is the much-heralded left tackle for a disappointing Ole Miss team. He's the subject of a book, "The Blind Side," by Michael Lewis, and he is set to be the subject of a 20th Century Fox movie due to start shooting in 2008. His personal story is perhaps even more stunning than his athletic ability. He's gone from nearly being a homeless high school drop out to the adopted son of a wealthy Memphis family on the cusp of NFL riches in just a few years. Oher plays left tackle, which has become one of the most valuable positions in the NFL because of that position's responsibility to protect a quarterback from defensive players he can't see coming. Lewis discovered when he started researching his book that left tackle has actually become the second best paid position in the NFL, trailing only quarterback -- a fact that surprises many NFL team officials, let alone fans. Oher, who is 6-foot, 6-inches tall and 322 pounds, is ranked as the No. 7 offensive draft prospect by SI.com, even though he's only a junior playing for a team that is 3-7 and winless in its conference games. College football players reaching the end of their junior season have to decide to enter the NFL draft or return to school for a final year. They can change their mind between the end of season and the NFL combine in February where teams evaluate the potential draft picks. But if they participate in the combine they are declaring an end to their college football career. If Oher or other top juniors do badly at the combine, or go lower in the draft than they expected, or even get an offer below what they they and their agents believe they are worth, they're left with few options. "If you had to design a system for screwing poor black kids who can play football without making it seem like slavery, you couldn't do much better than the NCAA has done," Lewis told me recently. That's not the case with potential pro athletes in other sports. Baseball players can be drafted in high school and negotiate with a team before deciding whether to enroll in college or sign with the club that drafted them. Basketball players who haven't been drafted and have not signed with an agent can also return to college if they decide quickly after the NBA draft they are better off playing another year. Of course, Oher is probably safer than a lot of other college juniors facing this decision. There aren't many college players with the build to be an impact left tackle. An he's had that build since high school, when he was still just learning the game. "It is true there's some risk. With Michael, there's as little risk as there can be," said Lewis. "What appeals to the NFL, what they're attracted to, is that he's an awesome physical presence. He's an incredible athlete. They see that raw potential." Still, the current NCAA rules represent little more than an unfair deal between the NCAA and the NFL. And that's to the detriment of fans of both sports. The NCAA is apparently of the belief that they would lose more fourth-year players to the NFL if they could test the waters before deciding whether or not to return. But the opposite is probably true. Star athletes, which virtually every NFL player is while in college, probably believe they are better and more valuable than they are. So if they went through the draft and got picked in the later rounds, they might be more likely to try college another year to improve their odds of a bigger payday down the line. And that extra year in college would improve not only the quality of the college game, but provide a supply of better-prepared players for the pros. As safe as Oher's prospects now appear, every year there are sure thing players with a year of eligibility left who drop far below where they expect to be drafted. And it costs them millions. Even for a player that is picked first in the draft, the lack of ability to return to college probably costs them the bargaining leverage they could use to get the contract they're seeking. JaMarcus Russell, last year's No. 1 pick, was able to get a record $29 million in guaranteed money from the Raiders as part of his six-year deal by holding out into mid-September. But he might have been able to reach the deal well before training camp started if he could have threatened to return to the powerful LSU team for his fourth season of eligibility. Lewis has become the champion and No. 1 cheerleader for teams that find hidden value in lower-priced draft picks. His first sports book, "Moneyball" about the Oakland Athletics baseball team, was a celebration of just that. So he would seem to be an unusual advocate of a change in rules that would be cheered by agents and bonus babies. But Lewis says he can't ignore how the bargaining table is tilted against college football players. "If you're a college star, your job is to play football, at least pretend to go to school, assume all the risk, generate millions of dollars for your university, and stay poor," Lewis said. "When you get near to a market where you can sell your services, they're going to make it as difficult as possible. I'm amazed there's not more outrage." |

| |||||||