(Fortune) -- It was one of America's most shocking political sex scandals, instantly transforming New York Gov. Eliot Spitzer -- who had terrified Wall Street during his political climb -- into the infamous "Client 9."

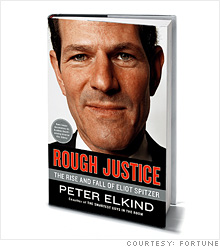

In Rough Justice, his new book out April 20, Fortune editor-at-large Peter Elkind breaks fresh ground in the remarkable tale of Spitzer's rise and fall. The book includes the first interviews with the operators of Emperors Club VIP, the high-priced escort service where Spitzer became a regular customer; explores his recurring relationship with one of its prostitutes (no, it's not Ashley Dupré); provides revelations about the extraordinary federal investigation that drove him from office; reveals how Spitzer's enemies in business and politics schemed to bring him down; and explains why Silda Wall Spitzer, his humiliated wife, decided to stand by him.

Elkind is co-author (with Bethany McLean) of the bestselling book on Enron , The Smartest Guys in the Room. Rough Justice is the product of an unusual collaboration with Academy Award-winning filmmaker Alex Gibney, whose Spitzer documentary premieres April 24 at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York City. We offer our readers this exclusive excerpt.

--Editor's Note: This story contains profanity.

In July 2007, North Fork Bank vice president Adam Brenner got a peculiar phone call from his branch's most prominent client, New York Gov. Eliot Spitzer. Brenner's private-banking office, on Madison Avenue and 49th Street in Manhattan, catered to wealthy New Yorkers, many of them involved in real estate. It prided itself on service.

"Is there a way to wire money where it's not evident that it's coming from me?" the governor asked. Brenner referred the matter to his superiors. They wouldn't make this anonymous wire transfer, even for the governor. It was against all sorts of banking regulations.

But the bankers noticed that the governor's desired recipient -- a company called QAT Consulting -- also had its account at a North Fork branch. They would make an intrabank transfer instead, anonymously. Even so, the incident clearly required reporting. Any unusual money transfers were supposed to be disclosed to banking authorities on a Suspicious Activity Report, known as an SAR. This was Banking 101 -- everyone at North Fork took an online course about it his first day on the job.

Politically prominent people received extra scrutiny because of their susceptibility to extortion or corruption. Spitzer's transaction generated an unusually detailed and lengthy SAR, which the bank sent to FinCEN -- the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, a branch of the U.S. Treasury Department with offices in Detroit.

There the SAR was entered into a database accessible to federal, state, and local law-enforcement agencies. FinCEN typically received more than 3,400 SARs a day. The North Fork filing would remain buried among them, unnoticed for months.

Unbeknownst to banker Brenner, QAT Consulting was a dummy corporation -- a front for a high-priced escort service called Emperors Club VIP. By mid-2007, Spitzer had long since become a regular customer, using the name of close friend George Fox. His awkwardness on the phone had disappeared as he learned the ropes of patronizing prostitutes. But he remained unusually guarded, and he refused to engage in small talk. "He practically attacked me when he walked in the door," one escort told her phone booker afterward. "He was just ready."

The first time "George Fox" had procured the services of an escort we'll call Angelina -- in late 2006 -- she didn't much care for him. "It was very businesslike," Angelina recalls. "He was not one of those people who I would have said went out of their way to make me feel lovely and nice, like many did. It was very impersonal."

The next time, she met Fox at the Waldorf-Astoria in Midtown Manhattan. It was late at night. He rushed into the room with a baseball cap on, clearly trying not to be recognized, and wanting to get right to it. She insisted they talk first. Angelina was being paid $1,200 an hour, but she operated by her own rules. With Fox, she recalls being "rather pushy," telling him, "Listen, we are going to sit and have a chitchat and have a nice little date here."

Surprisingly, he seemed to like it that she pushed back. He'd brought along some Scotch, so they sat down to talk over a few drinks while listening to classical music. She asked him what he did for a living. He said he was a lawyer. What kind of law? He dodged. He asked questions about her. They joked and laughed. Says Angelina: "It ended up being kind of a fun couple of hours."

Angelina came away from the session thinking she recognized her john. She looked closely at the photos in the newspapers and watched the TV news. And soon she was certain: She knew who George Fox really was. When her bosses came into the city to settle up, Angelina excitedly told them. He'd seen other girls. Didn't any of them recognize him? There'd been talk he might someday be President! Did they have any idea?

Not a clue.

Fox would continue to see other escorts from the Emperors Club over the months to come. But after his second visit with Angelina, he began to ask for her regularly, especially for out-of-town appointments. He rarely requested anyone else; previously he hadn't seemed to care whom he saw. He met with Angelina a half-dozen times.

As they fell into something approximating a routine, she wondered how he juggled it all. Fox clearly had more money than time. He paid for more hours than he'd use, just in case he was running late. Angelina would arrive first and wait for him in the room. Afterward he'd rush off. Angelina never noticed anyone around him -- no friends, no subordinates, no security. He came and went alone. "Clearly he was looking to get in and get out without being seen," she says. "It was clearly a personal thing -- no one's business, affecting no one. Just his business."

Angelina's time with Fox honed her interest in government and politics. She read a book written about him. She pored over his newspaper coverage. And as she followed his public battles, Fox's favorite escort was privately cheering him on. "Treating people with disrespect in any circumstance is wrong," Angelina said later. "And the way he went about it was wrong. But the stuff he was trying to do is admirable. And no one else is brave enough to do it. Whether that comes from narcissism or whatever -- it doesn't matter. It's like a real sense of justice."

"They got the wrong fucking guy!" Ken Langone, the billionaire investment banker, told me in his Park Avenue office. It was mid-2004. Langone's adult son, sporting a Mohawk haircut, was sitting in on this off-color tirade, directed against both Eliot Spitzer -- then New York attorney general -- and the Wall Street CEOs who were helping him make Langone a symbol of all that was wrong with executive pay.

As chairman of the compensation committee at the New York Stock Exchange, Langone had helped craft the shocking $140 million package awarded to NYSE chief Dick Grasso. Now Spitzer, claiming that Langone had duped his fellow board members, had sued both him and Grasso to recover the money, and Langone was livid. "I'm nuts, I'm rich, and boy, do I love a fight!" Langone declared.

If the usual playbook for political ascent in America was to make powerful friends, Eliot Spitzer's signature was making powerful enemies. Langone was just one of many. The list included an array of targets in corporate America and on Wall Street. Notable among them was Maurice "Hank" Greenberg, CEO of the insurance giant AIG and arguably the world's most influential businessman.

Spitzer understood the power of a lawsuit, as both a legal and a public relations document. His complaints told a story, with a keen eye for what would generate the most outrage. They invariably led with the most scandalous conduct and often included ugly details that weren't essential to the legal claims. Spitzer also knew how to cast a complex matter in simple, populist terms. Conflicts of interest in Wall Street research? "The largest consumer scam ever." Permitting market timing in mutual funds? Like a casino that "allowed favored gamblers to use loaded dice."

One of the things that drove Spitzer's enemies batty was just how gleefully he went about his business, exploiting his leverage to the hilt, moralizing about right and wrong, and peppering his public appearances with in-your-face remarks. David Brown, one of Spitzer's key lieutenants in the attorney general's office, marveled at his boss's clout.

"I admired him tremendously as a muscular populist liberal who wasn't afraid to confront business institutions by punching them in the nose," Brown says. "The M.O. was to keep things under wraps, announce them in a big way, then work with the press. You lay out all the appalling facts, and they're dead, because they're in the market. That's all you have to do. When he really had the facts on somebody, it was like something out of Wild Kingdom."

Spitzer's crusades against Wall Street made him the most powerful public official in America outside Washington, and the bête noire of the conservative establishment. The Wall Street Journal's editorial page attacked Spitzer regularly as an autocratic, anti-business meddler -- the "Lord High Executioner." The National Review branded him "the most destructive politician in America."

But rough justice made great politics. His poll numbers were off the charts, even among Republicans. Spitzer was the rare Democrat voters thought was tough. As he prepared to run for governor of New York in 2006, there was even talk about the attorney general as the leader of a new political movement -- "Spitzerism," the New York Times Magazine called it. Its premise was a populist appeal to the growing "investor class" -- the 50% of American families with money in the stock market -- and its hook was the theme of Spitzer's cases: Wall Street is taking you to the cleaners.

People jammed Spitzer's speeches to hear him talk about "fiduciary duty." They stopped him on the street, shouting, "Give 'em hell, Eliot!"

One day the attorney general stopped by to chew it all over with his PR man, Darren Dopp. "You know, boss, it's been a hell of a run," Dopp told him. "But if we ever so much as stumble, they'll be merciless. A single misstep and they'll stomp us in the nuts."

"I know," Spitzer replied. "That's why we can't have any missteps. I'm sure they've got people watching everything we do. And I'm sure that's been going on for a while."

After arriving in Washington and checking into his own room at the Mayflower Hotel, George Fox spoke to Temeka Lewis, the Emperors Club phone booker, to relay his cloak-and-dagger arrangements for meeting the escort known as Kristen.

Kristen, also known as Ashley Dupré, had begun working as a call girl at a different escort service more than three years earlier, when she was just 19, and dreamed of launching a music career. There, the phone booker sold her to johns as a future pop star. He delivered the pitch to callers: "Sir, can you imagine having an appointment with Madonna before she's famous? Think of the bragging rights you'll have! I'll have her bring one of her CDs!"

George Fox didn't know about her ambitions; he had never met her. He gave instructions that when she arrived at the Mayflower Hotel from New York, she should go straight to Room 871. The door would be slightly ajar but not visibly open, and there would be a key for her inside. The booker told George Fox that he owed a balance for the evening of $2,721.41, and that it would be ideal if he could give Dupré an extra $2,000 on top of that. He asked Lewis to tell him what Dupré looked like. She rattled off her escort profile: American, petite, very pretty, brunette, 5-foot-5, 105 pounds.

It was Feb. 13, 2008. By 9:32 p.m., Dupré had arrived in the room, located on a quiet club floor of the hotel, and called Lewis for an update. George Fox was already at the hotel and would be at her door soon. He would be giving her cash, Lewis explained: It would cover the balance of that night's four-hour booking -- his customary out-of-town minimum -- and provide extra money for future appointments. He arrived at about 10:15 p.m. and was gone by midnight.

Dupré immediately called her booker to deliver the escort version of an after-action report. Fox had given her $4,300, Dupré told Lewis. Despite his mixed reputation among the escorts, Dupré also said she liked him. Unlike some of her colleagues, she wasn't put off by a client who didn't bother much with small talk. In this life, Dupré, at age 22, had no pretensions. "I don't think he's difficult," she said. "I mean, it's just kind of like ... whatever ... I'm here for a purpose. I know what my purpose is." Lewis and Dupré, kicking back at the end of a challenging workday, continued their chatter.

The entire conversation was picked up by an FBI wiretap on the Emperors Club phone line.

The story went up on the New York Times website at 1:58 p.m. on March 10, 2008: "Spitzer is linked to prostitution ring". In some quarters there was open celebration. Whoops and cheers rang out on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange. Hank Greenberg, the deposed AIG titan, got the news in his Park Avenue office when a deputy burst into a meeting carrying a Bloomberg bulletin about the Times scoop.

"Get the fuck out of here!" Greenberg barked. "I'm working." Then he looked closer. Celebratory calls streamed in from friends, including an exultant Ken Langone.

"Bingo!" Langone shouted.

Hours after the scandal broke, a CNBC crew sought Langone's reaction outside a Tribeca restaurant when he arrived for a charity dinner organized by Dick Grasso. Langone began by calling Spitzer a hypocrite who "destroyed reputations" and who needed to resign immediately. "So how do I feel?" he mused. "I certainly feel sorry for his daughters. Very much so. I don't know his wife. But I gotta -- I have to assume she has some idea of this happening. For him?" Langone paused. "It couldn't be enough to please me."

Was he surprised at the news? "Not at all!" Langone replied. "I had no doubt about his lack of character and integrity. It would only be a matter of time. I didn't think he'd do it this soon, or the way he did it." Unable to stop himself, Langone went on: "But I know, for example -- I know for sure -- he went himself to a post office and bought $2,800 worth of mail orders to send to the hooker." Langone gave the reporter a knowing nod and grinned. Spitzer's personal visit to the Grand Central post office had not been disclosed anywhere. But it was a significant event in the government investigation.

"How do you know that?" the reporter asked. "I know it," Langone replied mysteriously. "I know somebody who was standing in back of him in line."

This was a sex scandal for the 21st century -- a global, cross-platform phenomenon, rippling instantly in every direction. It made headlines in the Philippines. Israeli papers lamented a setback for electing the first Jewish American President. On The View, Joy Behar treated it as proof that men -- especially powerful men -- are pigs. ("Viagra is destroying our government!") David Letterman told his audience, "I'm thinking, holy cow! We can't get bin Laden, but by God we got Spitzer!"

There was a fertile backdrop for conspiracy theories, woven from a combination of politics and hate. Spitzer had fallen during a period when the Bush Justice Department was immersed in its own scandal over brazenly political practices. The swath he'd cut through Wall Street had created powerful, bitter enemies with close ties to the Republican administration. And Spitzer's sharp-elbowed rise had antagonized a generation of federal prosecutors and regulators whom he had ridiculed and embarrassed. Indeed, there were so many people eager to plunge a dagger into Spitzer that it wasn't hard to imagine that one -- or more -- could have played a part in his undoing.

To be sure, Spitzer patronized prostitutes and broke the law -- for a longer period and with greater frequency than anyone knew. He had been a customer of the Emperors Club for at least two full years and spent more than $100,000 on more than 20 appointments with perhaps 10 escorts in New York City, Washington, Dallas, Palm Beach, and San Juan.

Yet many other prominent men have strayed -- why did Spitzer's sexual habits become the target of federal investigative methods befitting an al Qaeda terrorist? Did the investigation really begin with a routine IRS review that spotted a Suspicious Activity Report buried within a database containing millions of them? Or did someone tip off the feds?

This is uncertain terrain, muddied by incomplete information and vehement denials from people involved. But it is useful to carefully sort through precisely what is known -- and what isn't.

This exercise necessarily begins with Roger Stone, the self-described "GOP hit man," who clearly saw Spitzer's downfall as a business opportunity -- a chance to burnish his reputation as a cunning giant slayer. A master of showmanship and misdirection, Stone had a long history of claiming credit for sleazy things he hadn't done and denying responsibility for those he had. He'd been working to undermine Spitzer since the summer of 2007.

Now Stone launched three separate schemes to suggest that he had played a role in bringing Spitzer down -- none of which appear to hold up under scrutiny. The most successful of them unfolded just days after Spitzer's downfall, when Stone, who has a home in Miami Beach, told the Miami Herald that he had tipped the FBI about Spitzer's use of prostitutes.

As proof, he provided the paper a letter that one of his lawyers supposedly sent to the FBI in November 2007 reporting that Spitzer had "used the services of high-priced call girls" in Florida. Stone, according to the letter, had learned of these activities from "a social contact in an adult-themed club." (Translation, later offered by Stone himself: a hooker he'd met in a Miami swingers' club.) The letter also put in play the kind of salacious detail Stone loves, reporting that Spitzer "did not remove his mid-calf-length black socks during the sex act."

This juicy account, not surprisingly, received widespread media coverage; even the mainstream press has treated the black-socks detail as fact -- an opportunity for further Spitzer ridicule. Stone added links to the coverage on his website.

Unfortunately, almost everything about this tale appears to be fiction. FBI officials say they have searched for such a letter and have found no trace of it. (Says Stone: "I'm not surprised they would deny a tip from a citizen.") Spitzer's only known Florida assignation (with Angelina, who flew down from New York) came during a trip to Palm Beach in late February -- three months after the Nov. 19 date on the Stone letter.

As for the black socks, Spitzer and Angelina -- both in a position to know -- call that claim ridiculous.

Stone also planted a story about an anti-Spitzer cabal with a Florida-based political blog, according to the blog's author, a Fort Lauderdale attorney named Ron Gunzburger. While Stone denies doing so -- unpersuasively -- he does acknowledge that enemies of Spitzer in New York have bankrolled his ongoing attacks on the former governor, which continued long after Spitzer resigned.

Over breakfast in New York, Stone told me that he has been paid by a group of Spitzer haters, whom he declined to identify. But he insisted that it was just a small amount and that Greenberg and Langone were not among the contributors. "They were largely chickenshit," Stone declares. "They wanted to take him on, but they weren't willing to write checks."

Which prompts the next question in our speculation: Who might have hired Stone -- or even retained a detective directly to follow Spitzer around? Notwithstanding Stone's denials, Greenberg and Langone remain the most obvious suspects. "If I were an FBI profiler, I'd go right to those two guys," says Eric Dezenhall, a Washington crisis-management consultant who has represented many Wall Street clients and travels in anti-Spitzer circles. "They have the motive, the means, the opportunity, and the personality."

Greenberg had a long-standing reputation for deploying clandestine methods; he had contacts in the CIA, and he had used detectives at AIG (AIG, Fortune 500). Langone had a palpable thirst for revenge. He had hired a private investigator to find political ammunition to use against Spitzer during the run-up to his gubernatorial campaign.

In high-level Wall Street circles, there are persistent rumblings that Langone hired someone to shadow Spitzer. Some of the rumblings come from those with ties to Langone; other people claim to have heard it in social settings directly from Greenberg. On July 17, 2009, Fortune writer James Bandler, interviewing Langone for a magazine profile of Greenberg, asked, Did you hire a gumshoe? "I'd say, 'No comment,' " Langone responded.

On several other occasions he has flat-out denied it, through both his lawyer and a spokesman. His PR consultant, Jim McCarthy, vehemently insists that Langone simply "misspoke" on CNBC -- that he really didn't have any advance knowledge of Spitzer's involvement with prostitutes. Greenberg has also publicly denied knowing anything about the use of detectives against Spitzer.

The third big player in the Spitzer haters club, Grasso, offered his own hint of some foreknowledge about the governor's extramarital activities. In the epilogue to his book about Grasso, King of the Club, CNBC reporter Charles Gasparino writes that Grasso made a surprising comment to him about Spitzer in early 2007: "We hear he has something going with a young girl." Gasparino adds that when he asked Grasso about this remark more than a year later, after the prostitution scandal broke, Grasso "just laughed before hanging up the telephone."

Detectives are one possible explanation for how Spitzer's enemies might have known about his extramarital activities. Another is that they received information from Republican friends in the Bush administration's Justice Department, sharing a few juicy details about their mutual enemy. But ultimately, on these questions, at this moment, certainty remains beyond reach. We are left with nothing more than intriguing speculation.

Among those close to the former New York governor, one person is more devoted to these theories than anyone: Eliot Spitzer's wife. While privately struggling to make sense of it all -- she read books about relationships, spirituality, and the impact of high-stress jobs on adrenaline and testosterone -- Silda Wall Spitzer had come to conclude that her husband had fallen victim to a perfect storm.

His behavior had provided the opening. But he had so many enemies eager to move in -- from Albany, Wall Street, and Washington. They'd viewed him as a foreign body, disrupting how things were done. They were desperate to get rid of him. There wasn't proof; she wanted someone to find it. But 100 disparate threads of evidence fed her growing certainty: The bad guys had brought Eliot down.

Why had Eliot Spitzer paid for sex? He loved Silda. But he had needs. And in his maddeningly frenetic life, he acted to fulfill them, quickly and without complication. Money was not a problem. Says Marc Agnifilo, a lawyer representing Temeka Lewis, the Emperors Club booker: "There's something about Spitzer that liked the efficiency of this."

Plenty of politicians have affairs, but to Spitzer, such an arrangement -- while having the distinct advantage of not being against the law -- would be an even greater betrayal. "An affair begins to connote an emotional relationship," he explains. "If I had had an affair, I'd still be governor, but I might not be married. In the grand scheme of things, I'm glad I am where I am."

Well, up to a point. The year Spitzer fell, 2008, was when America began to learn the consequences of Wall Street's madness. The venerable investment-banking houses of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers collapsed, buried beneath the weight of unregulated investments in high-risk mortgages. A fund manager named Bernie Madoff confessed to operating a $50 billion Ponzi scheme. AIG became a ward of the state. Merrill Lynch was auctioned off for a pittance. Citigroup (C, Fortune 500) struggled to survive. The nation spiraled into recession.

It was a hard time to be Eliot Spitzer. New York's former governor stewed as he watched it all from the sidelines. He had warned Washington about subprime debt. He had prosecuted AIG for cooking its books. He had taken scorching heat for his showcase lawsuit over grotesque executive pay. Most of all, he had preached the perils of greed and hubris and deregulation run amok. He might have been heralded as a Cassandra. He might have been a major voice in the national debate about how to fix the mess -- perhaps even President Barack Obama's choice for U.S. attorney general.

Instead, Spitzer was cooped in a converted conference room at his father's Manhattan real estate office, nominally presiding over a family business empire that ran itself, reduced to wielding his political influence through media interviews and a column for an online magazine.

"I get up in the morning, make breakfast for the girls, put them on the bus, come to the office, read the papers, and I say to myself 10,000 times: 'I should be doing something else.'" ![]()

| Company | Price | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ford Motor Co | 8.29 | 0.05 | 0.61% |

| Advanced Micro Devic... | 54.59 | 0.70 | 1.30% |

| Cisco Systems Inc | 47.49 | -2.44 | -4.89% |

| General Electric Co | 13.00 | -0.16 | -1.22% |

| Kraft Heinz Co | 27.84 | -2.20 | -7.32% |

| Index | Last | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dow | 32,627.97 | -234.33 | -0.71% |

| Nasdaq | 13,215.24 | 99.07 | 0.76% |

| S&P 500 | 3,913.10 | -2.36 | -0.06% |

| Treasuries | 1.73 | 0.00 | 0.12% |

|

Bankrupt toy retailer tells bankruptcy court it is looking at possibly reviving the Toys 'R' Us and Babies 'R' Us brands. More |

Land O'Lakes CEO Beth Ford charts her career path, from her first job to becoming the first openly gay CEO at a Fortune 500 company in an interview with CNN's Boss Files. More |

Honda and General Motors are creating a new generation of fully autonomous vehicles. More |

In 1998, Ntsiki Biyela won a scholarship to study wine making. Now she's about to launch her own brand. More |

Whether you hedge inflation or look for a return that outpaces inflation, here's how to prepare. More |