(Fortune) -- We're with R.E.M. when it comes to the end of the Federal Reserve's quantitative easing program: "It's the end of the world as we know it (and we feel fine)." Michael Stipe isn't known for his musings on monetary policy, but it's a good metaphor -- for now.

The unprecedented program, which in late 2008 began injecting over $1 trillion into our economy -- mostly through the purchase of mortgage debt issued or guaranteed by Fannie Mae (FNM, Fortune 500) and Freddie Mac (FRE, Fortune 500) -- has come to a close as of March 31st. And we're all still standing.

While many market observers expected the ending of this policy to lead to an increase in interest rates, particularly for mortgages, we have seen only a marginal change. In fact, over the last three weeks, 30-year fixed mortgage rates have only increased from 5.05% to 5.25%. In essence, the quantitative easing world has ended, which could've led to a scenario where everybody hurts. Instead, people getting new mortgages still "feel fine."

To its credit, the Federal Reserve did an effective job at prepping the market for the end of this policy, so new, private buyers were ready to step in and keep the mortgage market stable. Backing up for a second, though: What exactly is quantitative easing?

Central banks have two key tools to implement monetary policy: interest rates and reserve requirements. By lowering interest rates, central banks make rates more reasonable for borrowers and profit margins more compelling to lenders. This stimulates the supply of money in the economy.

On the reserve front, the central bank can alter bank reserve requirements -- that is, the ratio of cash a bank must hold compared to its customer deposits. By lowering them, for example, they increase the amount of money the banks can lend out.

In the scenario where interest rates for banks are basically zero and reserve ratios have been maxed out -- like the one we're in right now -- central banks have another policy tool: quantitative easing. In simple terms, central banks start purchasing financial assets that financial institutions will sell to any investor on the open market.

In the United States' case, these assets were primarily mortgage debt that allowed Fannie and Freddie to keep the housing market afloat. To buy these assets, i.e., debt, the Federal Reserve prints money -- which it has a license to do, really -- increasing the excess reserves on the balance sheet of banks. Excess reserves are money the banks just can't put to use, so they leave it parked in accounts at the Fed, where it collects a small amount of interest.

World leader pretend?

The Bank of Japan used quantitative easing in the early 2000s in an attempt to offset deflation, with limited results. In November of 2008, the United States implemented its first ever policy of quantitative easing. The policy had two aspects to it. First, the Federal Reserve said it would purchase debt from Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Home Loan Banks. Second, the Federal Reserve said it would purchase mortgage-backed securities.

The objective of this program, according to the Federal Reserve, was to "reduce the cost and increase the availability of credit for the purchase of houses, which in turn should support housing markets and foster improved conditions in financial markets more generally." Basically, as credit markets ground to a halt in late 2008, the Federal Reserve had to become the buyer of last resort, to keep deflation from happening.

While the program started on a smaller scale with just $500 billion of mortgage-backed debt, it was ramped up in March 2009. By March 31, 2010, the Federal Reserve had purchased $1.2 trillion of mortgage-backed securities from banks and $200 billion of direct obligation debt of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, for total purchases of $1.4 trillion. As a result of these actions, the Federal Reserve now owns almost 25% of the stock of mortgage-backed bonds.

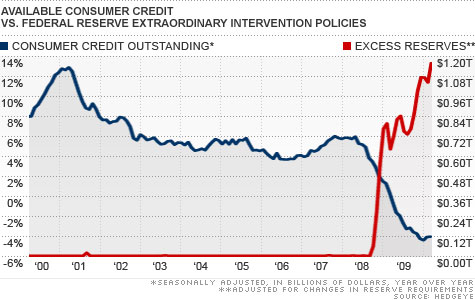

In the chart above, we show how dramatic the increase has been on bank balance sheets. The current amount of excess reserves is estimated to be $1.2 trillion. Assuming that banks turned these excess reserves into loans at a typical 10:1 ratio, the increase in money supply would be $12 trillion. That's more than the current amount of outstanding mortgages in the United States!

We also compare excess reserves to the huge declines in consumer credit outstanding. The period that consumer credit outstanding started to decline correlates closely with the buildup in excess reserves. Combined, these two data sets suggest that even as available credit is shrinking, banks are sitting on huge amounts of reserves they don't want to lend out.

What's the frequency, Kenneth?

The reality is simply this: we have no idea what the long-term consequences of this quantitative easing policy action will be. Starting and stopping it were both unprecedented moves, and what the Fed owns now will have to be, in time, unwound. If the unwinding is natural, with banks reducing their excess reserves to a more normal level, the inflationary impacts on the U.S. economy could be extraordinary.

At this point, I'm not going to predict the "end of the world as we know it" due to this massive increase in excess reserves, but the money has to go somewhere. Either the Federal Reserve will have to raise the small interest rates it pays on these reserves to keep discouraging banks from using the money, or the banks will begin to lend. And lend. And lend. And possibly reinflate the credit bubble that caused us so much pain in 2008.

We can say this: If the $1.2 trillion in reserves starts to make its way into the economy, money supply will increase dramatically and with it inflation. So, while there's a lot of talk about inflationary pressures, very few people have yet to consider inflation: the big, unintended consequence that looms, thanks to quantitative easing.

Daryl G. Jones is the Managing Director of Risk Management at Hedgeye, a research firm based in New Haven, Conn. His colleagues Darius Dale also contributed to this column. ![]()

| Company | Price | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ford Motor Co | 8.29 | 0.05 | 0.61% |

| Advanced Micro Devic... | 54.59 | 0.70 | 1.30% |

| Cisco Systems Inc | 47.49 | -2.44 | -4.89% |

| General Electric Co | 13.00 | -0.16 | -1.22% |

| Kraft Heinz Co | 27.84 | -2.20 | -7.32% |

| Index | Last | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dow | 32,627.97 | -234.33 | -0.71% |

| Nasdaq | 13,215.24 | 99.07 | 0.76% |

| S&P 500 | 3,913.10 | -2.36 | -0.06% |

| Treasuries | 1.73 | 0.00 | 0.12% |

|

Bankrupt toy retailer tells bankruptcy court it is looking at possibly reviving the Toys 'R' Us and Babies 'R' Us brands. More |

Land O'Lakes CEO Beth Ford charts her career path, from her first job to becoming the first openly gay CEO at a Fortune 500 company in an interview with CNN's Boss Files. More |

Honda and General Motors are creating a new generation of fully autonomous vehicles. More |

In 1998, Ntsiki Biyela won a scholarship to study wine making. Now she's about to launch her own brand. More |

Whether you hedge inflation or look for a return that outpaces inflation, here's how to prepare. More |