Search News

(Fortune) -- When Steve Greenberg was trying to launch Classic Sports Network (CSN) in 1993, he and his partner, Brian Bedol, hit nothing but roadblocks. Neither had any experience running a cable network. Some people thought their idea to rebroadcast archival footage of big games was interesting, but nobody wanted to give them money. Then Greenberg went to see Herbert Allen Jr. at Allen & Co., the fabled investment-banking boutique.

Greenberg was 44 years old and feeling restless. He had recently resigned as deputy commissioner of Major League Baseball. His old boss there, Fay Vincent, who had gone to Williams College with Allen and had run Columbia Pictures when Allen & Co. owned it in the late '70s and early '80s, set the meeting up. Allen was happy to talk to young Greenberg. He had known his dad, Hank. Not AIG Hank; Hammerin' Hank, the slugging first baseman for the Detroit Tigers in the '30s and '40s.

Allen asked Greenberg what his plans were. Greenberg told him he was considering two opportunities: Mets owner Fred Wilpon, a good friend, had approached him about working for the team in an executive position. But what really interested him, Greenberg said, was the idea Bedol had brought him for the Classic Sports Network.

"Can you get the rights?" was Allen's first question.

"Yeah," said Greenberg, "I think we can."

"Are you gonna run it?"

"Yeah, with Brian."

"That'll be the only thing you do day to day?"

"Yeah, that'll be my job."

"Are you looking for money?"

"Well, we need some seed capital to launch it."

"How much?"

"Six million dollars."

"Would it help or hurt if Allen & Co. put in $2 million?"

Greenberg paused. "I think that would probably help."

"Okay, we're in for $2 million. Call our CFO this afternoon. Tell him where to wire the funds."

That's the real-time account of what happened, not the condensed version. Only after Allen had agreed to pony up did he ask what percentage of the company he was getting. Greenberg told him 25%; Allen said that would be fine. Greenberg offered to show him a business plan, but Allen waved him off. "I have a bunch of very smart Harvard MBAs running around here who think their job is to protect me from myself," Allen said. "Don't ever show anyone here your business plan." With Allen's backing secured, it took Greenberg and Bedol about a week to raise the other $4 million, and two years to get the network up and running. In 1997, when ESPN bought CSN for $175 million, Allen & Co. realized a 600% return on its investment. Later Allen & Co. would invest in a second Bedol-Greenberg collaboration, College Sports TV (CSTV), and the results were again spectacular. It was sold to CBS in 2006 for $325 million, and Bedol went along to continue running it.

And Greenberg? Having proven his worth, he was made partner at Allen & Co. in 2002 -- and over the past decade he not only has made sports dealmaking a signature of the firm but has become arguably the most important dealmaker in sports. "Completely changed the game for us internally," says the current president, Herbert Allen III. "One of the leading -- if not the leading -- person in the firm today," says Herbert Allen Jr. "Clearly in the center of the universe," says MLB commissioner Bud Selig. Think about that. Hank Greenberg is in the Hall of Fame. Steve Greenberg, his son, is also a star -- in business.

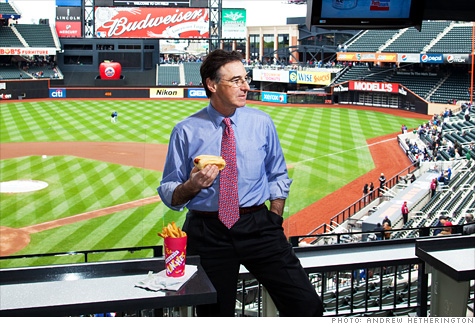

Greenberg, now 61, doesn't get a lot of press. Allen & Co. doesn't even have a website: that's how much it values discretion. And Greenberg makes a point of not returning reporters' phone calls. He's the ultimate backroom player, never one to steal headlines from his clients. But consider: Greenberg was the force behind the creation of MLB Network, widely regarded as the most successful cable launch in history. He created regional sports channels in Chicago for Jerry Reinsdorf, who owns baseball's White Sox and basketball's Bulls, and in New York for the Wilpon family; then he got the Wilpons a record $400 million for the naming rights to Citi Field. He advised the Selig family on the sale of baseball's Milwaukee Brewers and counseled entrepreneur Dan Gilbert on the purchase of basketball's Cleveland Cavaliers. Right now he's working with former AOL (AOL) vice chairman Ted Leonsis, who's buying the NBA's Washington Wizards, together with the Verizon Center, from the estate of legendary team owner Abe Pollin. Leonsis already owns the NHL's Washington Capitals, which means that when the deal closes he'll become the only individual to own both big-league winter sports teams in a top-five market (Washington and Baltimore combined), plus the arena where they play. That's a big deal.

"He's Keyser Söze," says John Ourand, a reporter for Sports Business Journal, comparing Greenberg to the elusive but omnipresent kingpin in the 1995 cult film The Usual Suspects. "He seems to be everywhere." The analogy isn't perfect. Söze's a thug, whereas Greenberg is preternaturally, embarrassingly charming. "Immensely attractive as a human being," says Herbert Allen Jr. "Able to get good results without making enemies," says Reinsdorf. "Always keeps his cool," says Wilpon. "Incredibly knowledgeable and connected," says Jim Delany, commissioner of the Big 10 Conference. (Greenberg made a cable network for him too.) Have we mentioned yet that in his seventh decade he's still got a full head of hair, minimal gray, and no paunch? "Able to eat three, four, five desserts every meal," says Gilbert, unhappily, "and never gain any weight." His nickname, bestowed upon him by his daughters, is Mr. Perfect.

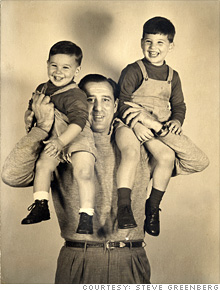

Funny thing about his famous dad, says Greenberg, lifting his eyebrows: "He was a great disappointment to his family." Hank Greenberg was first generation in America, born to Romanian Jewish immigrants who settled in the Bronx. His parents' dream -- the American dream -- was to send all their kids to college. Three of the four graduated. "My dad went for a semester to NYU, then went off to play ball," says Greenberg. "It was almost an embarrassment."

Steve had to balance a more complicated set of expectations. He grew up privileged and rich (Hammerin' Hank married a Gimbel heiress), attending St. Bernard's in Manhattan, then Hotchkiss, then Yale, where his brother, Glenn, had preceded him and where Steve was captain of the baseball team. (Glenn is now a money manager in New York; their younger sister, Alva, owned an art gallery.) Steve graduated in May 1970, got married a few days later, and while he was on his honeymoon he got drafted by the Washington Senators. The team gave him a $5,000 signing bonus and $500 a month and sent him to Geneva, N.Y., home of the Class A Geneva Senators of the New York--Penn League.

"It was something I really loved to do and I was pretty good at," says Greenberg, over a Cobb salad at Michael's restaurant in Manhattan. He's at table 27 in the front room, back to the wall, as powerful a perch as any in New York -- yet his voice carries a tinge of regret. "The fact that he" -- his father -- "had done it, I think if anything, foolish as it may sound, gave me the encouragement that I could do it too. I never had any illusions that I would be a Hall of Famer. But I knew there were a lot of gradations of major leaguers below Hall of Famer, and I thought that I would slot in there somewhere."

The younger Greenberg was a slick-fielding, right-handed first baseman with occasional power who got "every inch out of his ability," says Hal Keller, the farm director who drafted him. But he never got the call, and after five seasons, the last three at AAA, he quit to go to law school at UCLA. Greenberg insists it was an easy transition. ("I loved everything about law school.") But it was a year before he could bring himself to attend a big-league game. "I couldn't go out to Dodger Stadium," Greenberg says. "Just couldn't do it." He still gets wistful about what might have been. Wouldn't it be "kind of cool," he says, "to have a line in the Baseball Encyclopedia under my dad?"

All his life, people have been asking Greenberg, "What was it like to grow up as Hank Greenberg's son?" He doesn't know how to answer that. Hank Greenberg retired in 1947. Steve was born in 1948. "I never saw him play a game. I didn't know him," he says the next time we meet, pointing at one of many photographs of his father among his office memorabilia -- Hank Greenberg with Babe Ruth, Hank Greenberg with Joe DiMaggio. "I read about him. The guy I knew was a baseball executive [with the Indians and the White Sox], an avid tennis player. My dad taught me how to hit a tennis ball and comb my hair. But I didn't know this icon."

Indeed, tennis, not baseball, is what finally brought father and son together. During the years that Steve was practicing law in Los Angeles, they used to play two or three days a week at the Beverly Hills Tennis Club -- Hank had by then moved to L.A. -- and afterward they'd have lunch. Johnny Carson, Neil Simon, and Walter Matthau would sometimes stop by their table. As a Jew of a certain generation, Matthau grew up worshipping Hank Greenberg. The reason he joined the club, he later claimed, had nothing to do with tennis. He didn't even play. It was so he could eat lunch with Hank Greenberg.

Another frequent lunch companion in those days was a young associate at the law firm where Steve worked named Arn Tellem. Like Matthau, Tellem idolized Hank Greenberg. He says he joined Manatt Phelps & Phillips specifically for the chance to work with his son. ("I used to hang out outside his office, hoping to get an assignment," Tellem says.) Together they began representing athletes in contract negotiations.

Greenberg had already started making a name for himself as a dealmaker, with an evenhanded, respectful style that foreshadowed his career in investment banking. "He taught me a way to try to enlist the other side to view it as a shared experience, looking for the right result," says Tellem. "To be principled and strong, but to always put yourself in the other person's shoes and understand where they're coming from. He was a huge influence on me."

Tellem went on to become one of the top agents in sports (his clients include L.A. Angels slugger Hideki Matsui and the Chicago Bulls' Derrick Rose), but Greenberg, even as agenting was becoming obscenely lucrative, grew restless. His father died in 1986. His favorite clients, friends he had played with in the minor leagues, were retiring. There was a bitter dispute with one ex-teammate he had represented, Bill Madlock, that led to a lawsuit and lingering ill will. (They haven't spoken since.) Then one day in early September 1989, a letter arrived from Bart Giamatti, the commissioner of baseball.

Giamatti had taught Greenberg when he was a professor at Yale -- an English class on Spenser. Now, with labor troubles brewing, Giamatti and his deputy, Vincent, needed someone on their team who had credibility with the union. "We have to hire Steve Greenberg," Giamatti said to Vincent one day. "Doesn't he belong with us?" Vincent, who had served with Greenberg on the board at Hotchkiss, agreed, but only a day after Giamatti wrote Greenberg ("Would you like to move East? I kid not"), he suffered a heart attack at his home on Martha's Vineyard. "By the time Steve got the letter," says Vincent, "Bart was dead."

Greenberg came East anyway, as the new deputy to Vincent, the new commissioner. It was a big promotion for a 41-year-old ex-ballplayer turned agent. Many owners doubted his loyalty. But Vincent believed, "and I was only 100% right about this," he says, "that the only way to make progress with the players was to bring someone onboard for whom they had total respect and whose honesty they could not question." In fact it was Greenberg, working behind the scenes with union chief Donald Fehr, who negotiated an end to the 1990 baseball lockout, which had wiped out spring training and delayed opening day. "When it got down to the last week or two, we didn't have formal meetings," says Reinsdorf, who was on the owners negotiating committee. "The two of them made the deal." Four years later came the strike that canceled the '94 World Series, but by then Vincent had been canned by owners eager for a fight, and Greenberg the conciliator had moved on.

Ted Leonsis learned of Abe Pollin's death two days before Thanksgiving last year in a phone call from a reporter. He was shocked, but he wasn't surprised. Leonsis, 53, and Pollin, who was 85 when he died and had been an NBA owner for nearly half a century, had long been partners in the Wizards and the Verizon Center. Their agreement was that when Pollin died, Leonsis would have the exclusive right to negotiate with Pollin's estate for Pollin's majority share in both properties. If they could agree on a price within 10 days, great. If not, they'd bring in an appraiser.

A couple of years ago, with Pollin in failing health, Leonsis had gone looking for a banker to help him prepare for the inevitable. Leonsis talked to Goldman Sachs (GS, Fortune 500), which wound up representing Pollin, but quickly settled on Allen & Co. He had dealt with Greenberg once before, when AOL was considering buying CSN, and remembered him as "thoughtful, with a high level of integrity. He struck me as someone who would not oversell and under-deliver."

The choice paid off well before the Pollin talks arose. Last summer Greenberg invited Leonsis to the Allen & Co. conference in Sun Valley. Dinner on day one was under the stars, everybody together. Leonsis sat at a table with Greenberg's other guests -- Reinsdorf, Gilbert, and the Wilpons, Fred and Jeff -- and he had a memorable time. ("Just a wonderful sports night!") Day two, around dinnertime, Leonsis fell into a walking conversation with American Express (AXP, Fortune 500) CEO Ken Chenault. He followed him across the grounds, through the back door of someone's house (it turned out to be Herbert Allen's), and into the dining room. Bill Gates was there. Also Rupert Murdoch and LeBron James. Leonsis sat down next to Chenault. He wasn't supposed to be there, but he didn't know it, and the others were too polite to tell him.

All night long Leonsis talked to Chenault about a technology company he had started with Steve Case called Revolution Money. Chenault was intrigued. Next day, he collared Leonsis to find out more. Later they would meet in New York, but that was just the icing on the deal; the cake was baked in Sun Valley. Three months later, in one of the biggest tech buyouts of 2009, American Express acquired Revolution Money for $300 million -- with Allen & Co. advising the seller, naturally.

That deal closed just as the Pollin negotiations were heating up. Greenberg was determined to reach an agreement without resorting to an appraisal. Not that he didn't like his chances if it came to that; he thought it would be nearly impossible for an outside party to put an inflated price on any asset during what still felt like a recession. But he couldn't be sure. And when Greenberg himself looked closely, all he could see was the upside.

Fixing the Wizards -- who lost their star player, Gilbert Arenas, for most of the season on a gun conviction and failed to make the playoffs for the 17th time in 22 years -- would not be easy. Arenas is still owed $80 million. But Greenberg had watched while Leonsis transformed the lowly Capitals into one of the top franchises in the NHL and was willing to bet he was up to the challenge. Greenberg was bullish on the long-term prospects for the league. He was dreaming about the potential for a new TV deal down the road. "Both the teams are subject to existing arrangements with Comcast, but one always plans for the future," says Greenberg. "Obviously when you control two major-league teams in a four-team market, and both winter teams, you're thinking about bringing all that together." And he was mindful of the way sports franchises have performed as investments; barring mismanagement, they only go up. To which Leonsis, who was among the largest private owners of AOL stock before its ill-advised merger with Time Warner, can attest: "I don't have a single investment that performed as well or better in the last 10 years than my sports teams," he says.

The two parties started out "11 time zones apart," says Greenberg. The deadline passed. But with both parties reluctant to call in the appraisers, they kept talking. Finally, in late March, they settled on a number: $550 million for the team and the building, total value. The deal is expected to close in June. "Some people will say we overpaid," says Leonsis. "I might think we underpaid." Greenberg might think so too, but he's not saying. Next deal. ![]()

| Company | Price | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ford Motor Co | 8.29 | 0.05 | 0.61% |

| Advanced Micro Devic... | 54.59 | 0.70 | 1.30% |

| Cisco Systems Inc | 47.49 | -2.44 | -4.89% |

| General Electric Co | 13.00 | -0.16 | -1.22% |

| Kraft Heinz Co | 27.84 | -2.20 | -7.32% |

| Index | Last | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dow | 32,627.97 | -234.33 | -0.71% |

| Nasdaq | 13,215.24 | 99.07 | 0.76% |

| S&P 500 | 3,913.10 | -2.36 | -0.06% |

| Treasuries | 1.73 | 0.00 | 0.12% |

|

Bankrupt toy retailer tells bankruptcy court it is looking at possibly reviving the Toys 'R' Us and Babies 'R' Us brands. More |

Land O'Lakes CEO Beth Ford charts her career path, from her first job to becoming the first openly gay CEO at a Fortune 500 company in an interview with CNN's Boss Files. More |

Honda and General Motors are creating a new generation of fully autonomous vehicles. More |

In 1998, Ntsiki Biyela won a scholarship to study wine making. Now she's about to launch her own brand. More |

Whether you hedge inflation or look for a return that outpaces inflation, here's how to prepare. More |