Search News

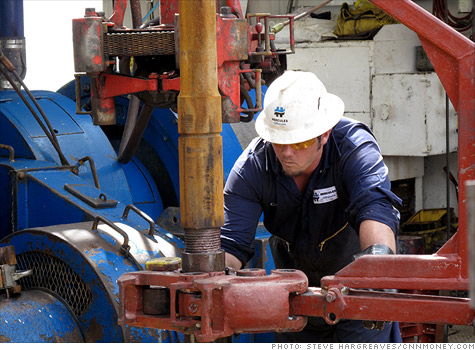

Michael Broom, a roughneck from Columbia, Miss., connects pieces of drill pipe on a Hercules Offshore rig, a few miles from Port. Fourchon, La.

Michael Broom, a roughneck from Columbia, Miss., connects pieces of drill pipe on a Hercules Offshore rig, a few miles from Port. Fourchon, La.

NEW ORLEANS (CNNMoney.com) -- On a wind-beaten drilling rig a few miles off Louisiana's coast, things are getting dicey.

"We have real rough conditions this morning," rig boss Greg Bramlett -- aka Mountain Man -- tells his crew during a shift change. "Seas are running eight to 10 foot swells."

With Hurricane Alex churning up the Gulf of Mexico, Bramlett is talking about the weather. He might as well be speaking of his livelihood.

Kissing that paycheck goodbye: Of all the people employed in the Gulf with lots to lose from the BP spill, oil workers are at the top of the list.

The oil industry is a $150 billion-a-year business in the Gulf, slightly bigger than tourism and dwarfing the $1 billion fishing industry.

With a government-imposed temporary ban on deep water drilling and permits for new shallow water wells stuck in limbo, roughnecks, roustabouts, and others in this field are nervous.

Their fear: When the wells they are currently drilling are finished, their jobs will disappear.

"We've been lucky so far, but other members of my family haven't been so lucky," said Michael Broom, a 28-year old roughneck on Bramlett's rig, which is owned by Hercules Offshore and is drilling a well for Chevron.

Like many young people that work on drilling rigs, Broom was attracted to the industry by the high pay and the generous time off.

Shallow water drillers work 14 days in a row and then have 14 days off. When they're on, they work 12 hours at a time, and have 12 hours free. They sleep in bunk beds, six to a room.

Downtime on the rig is usually spent on the basics -- sleeping, showering, eating and calling home. If there's time, they'll watch TV in the lounge.

"I love my job; it's like a second family out here," Broom said. "And when I'm home, I have plenty of time with my own family, and time to hunt and fish."

Salaries for rig workers start at $40,000 a year, Broom said. The newbies, or roustabouts, usually perform relatively unskilled jobs -- transferring freight from the boats, cleaning equipment and other odd jobs.

One step up from that is a roughneck like Broom. Roughnecks work right next to the spinning drill. They attach the drill pipe, clean mud from the hole and maintain the equipment. He says he makes over $60,000 a year.

"I wasn't a college kid, and I had to do something to support a family," Broom said. "We make more than most college graduates."

Shallow water drilling mired in red tape: New permits to drill in waters less than 500 feet deep are hard to come by these days. The Deepwater Horizon disaster and tough new safety standards for shallow water drilling have seen to that.

Drilling industry executives have been lobbying hard to get the permits reinstated. They say their operations are much safer than the deep water rigs like BP's.

They've been drilling these waters for a long time, so they know how much pressure to expect out of each well. The equipment that cuts off the well in case of a blow out is mounted right under the rig, making it easier to maintain and fix. And a major spill due to drilling hasn't happened in the shallow water parts of the U.S. Gulf.

The executives say that if new permits aren't issued soon, the rigs will go elsewhere, leaving workers out of a job and the country even more dependent on imported energy.

But environmentalists and others argue that spills have occurred in shallow water before, pointing to the Santa Barbara blow out in 1969, a spill in Mexican waters in the late 1970s, and a recent one off the coast of Australia. They say the permits should be put on hold until new rules are implemented and the federal agency overseeing drilling is reformed.

Not much sympathy: Others that depend on the Gulf for their livelihood have mixed feelings about whether drillers should be given the green light right away.

"There's an awful lot of people employed in the oil industry down here, and they're having a hard time," said Richard Forester, executive director of the Mississippi Gulf Coast Convention and Visitors Bureau. "If you continue to decimate jobs, it's going to have a hit on the economy."

To states to the east, where oil doesn't dominate the economy, the story is different. In Florida, it's about tourism, which brings the state $60 billion a year.

Jesse Brown runs the Native Cafe, a family-style restaurant on Pensacola Beach.

Brown feels bad for the workers, and wants them to continue drilling as soon as possible.

But he also thinks another BP-type spill can never happen again. He thinks the government should have the time to get things right, even if that means months of no drilling and the associated job losses.

"Yeah, it sucks, they can't drill," he said. "But they can get in the BP claims line or get in the unemployment line, just like the rest of us." ![]()

| Index | Last | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dow | 32,627.97 | -234.33 | -0.71% |

| Nasdaq | 13,215.24 | 99.07 | 0.76% |

| S&P 500 | 3,913.10 | -2.36 | -0.06% |

| Treasuries | 1.73 | 0.00 | 0.12% |

| Company | Price | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ford Motor Co | 8.29 | 0.05 | 0.61% |

| Advanced Micro Devic... | 54.59 | 0.70 | 1.30% |

| Cisco Systems Inc | 47.49 | -2.44 | -4.89% |

| General Electric Co | 13.00 | -0.16 | -1.22% |

| Kraft Heinz Co | 27.84 | -2.20 | -7.32% |

|

Bankrupt toy retailer tells bankruptcy court it is looking at possibly reviving the Toys 'R' Us and Babies 'R' Us brands. More |

Land O'Lakes CEO Beth Ford charts her career path, from her first job to becoming the first openly gay CEO at a Fortune 500 company in an interview with CNN's Boss Files. More |

Honda and General Motors are creating a new generation of fully autonomous vehicles. More |

In 1998, Ntsiki Biyela won a scholarship to study wine making. Now she's about to launch her own brand. More |

Whether you hedge inflation or look for a return that outpaces inflation, here's how to prepare. More |