FORTUNE -- Accounting -- exciting? After a global financial crisis that hinged on the misvaluation of assets, it's a lot more interesting than it used to be, and even more interesting if you're running one of the Big Four accounting firms. Talk about juggling constituencies: Ernst & Young CEO James Turley must respond to newly skittish clients, to recession victims who think accountants failed at their job, and to regulators worldwide who are certain that accounting rules must be changed -- they're just not sure how.

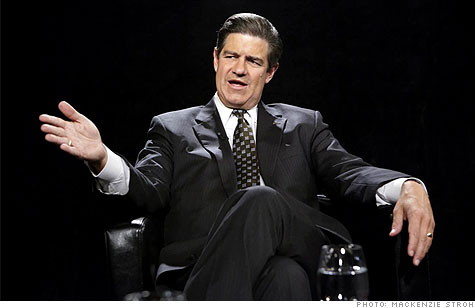

Turley, 55, who grew up in St. Louis and has both bachelor's and master's degrees in accounting from Rice University, is an E&Y lifer. He has run the partnership since 2001, when Enron's collapse began a wave of accounting scandals that reshaped the industry. After Arthur Andersen failed in 2002, many of its offices around the world joined E&Y intact, expanding the firm significantly. Today E&Y has about 144,000 employees in 140 countries; though Turley has homes in London and suburban New York, he spends 75% of his nights elsewhere. He talked recently with Fortune's Geoff Colvin about being the CEO of Lehman Brothers' auditing firm, why America's tax policy is globally uncompetitive, and much else. Edited excerpts:

Q: The new Dodd-Frank law, dramatically re-regulating financial services, is intended among other things to reduce risk in our financial system. Will it?

A: The most important thing about the Dodd-Frank bill is that it's become law. There was so much uncertainty that it's a good thing that it's done -- though an enormous amount of rulemaking still has to take place, so there's a whole lot of continuing uncertainty. Do I think it's going to reduce risk? Yes. The bill addresses some of the gaps in the regulatory system that became evident during the financial crisis. Do I think it's ironclad to prevent another crisis? No, I don't think anyone can say that.

Whenever you reduce risk, there's a cost. What's the cost here?

You always have a risk-growth trade-off, and one of the things this country needs -- this world needs -- is more growth. I spend a lot of time around the world, and you've heard of this LUV recovery people talk about. We're seeing it in spades. L-shaped across Europe -- they've gone down a long way, stayed flat for a good long time, I'm afraid -- U-shaped here in North America, and V-shaped in the emerging markets.

One of the central problems in the financial crisis was the valuing of highly complex securities. Signing off on those valuations is part of the auditor's job. Are accounting firms partly to blame for what went wrong?

If you look at the last two crises, it's instructive to compare and contrast. The crisis at the beginning of this decade, characterized by a very large number of financial restatements, could quite rightly be called an accounting and auditing crisis. What we've just seen and are emerging from is really an economic crisis. You saw credit bubbles, housing bubbles, asset values changing a lot. I've heard others, not in the accounting profession, saying the profession actually did a very good job because you haven't seen the kind of financial restatements that we saw in the early part of the decade.

We've also heard the argument that if we hadn't had mark-to-market rules that were expanded after that earlier crisis, forcing financial firms to tell the world just how much their assets had declined in value, we would have been better off. Do you agree?

No, I don't. I strongly believe that anything that provides more information in a more usable format for investors is good for the system. But I think there's a very legitimate question the profession's wrestling with now. If you have few if any financial restatements, yet you still have the financial crisis we experienced, then some could rightly say, What's the relevance of the historical financial information, even when it's marked to market?

In other words, if those financial statements were all correct, yet they didn't tell us what was going to happen, then do they need to be changed or improved?

Precisely. What information is needed by investors to make the right decisions? Do you need more forward-looking information, more on key performance indicators, more around environmental impact and sustainability? This is clearly not just an issue for the profession. It's something that regulators around the world are starting to talk about.

The Dodd-Frank law includes a clawback provision on executive pay, so executives could be made to give money back if earlier results have to be restated. Will that make CEOs even more interested in accounting than they are already?

I think it makes sense -- there's such a focus on the impact of compensation, not just the levels of it but also the incentives. So I think it's actually a quite logical reaction to what we've lived through. I don't think it's going to have a substantial impact on whether CEOs love their accountants.

Ernst & Young was the auditor for Lehman Brothers. The bankruptcy court examiner issued a report stating, "The examiner concludes that sufficient evidence exists to support colorable claims against Ernst & Young for professional malpractice" -- "colorable" being a legal term that means "plausible." How do you respond to that finding?

We put the facts on the table for our clients and other interested parties and helped people understand what an examiner's job is. First and foremost, an examiner is part of the bankruptcy court whose job is to do everything he can based on very deep investigations to identify colorable claims. He's not a finder of fact. He's not a judge and jury.

What was really more enlightening in the report was that he did not take exception to the fair values you talked about earlier, did not question the balance sheets or income statements of our last audit or the quarters subsequent. He did question whether there could or should have been, in his opinion, more disclosure around some of the repo financings that Lehman entered into.

After the report, there was speculation that the SEC could file civil charges against Ernst & Young, or there could even be criminal charges from the Justice Department. Have you had any indications one way or the other about any of that?

In the environment we're in, there are certainly going to be regulators investigating Lehman and all the other institutions that have gone through this circumstance, and of course there are civil actions, things that Ernst & Young deals with regularly, but I shouldn't comment on that.

It's important to put in context the time in which all this took place. Bear Stearns was going bankrupt -- the U.S. government funds an acquisition. Freddie and Fannie were going bankrupt -- the U.S. government takes them over. The government says, "You know, we can't bail out everybody, so let's let the next one fall." Then it says, "You know what? That didn't work very well." The next day or next week, $100 billion-plus to AIG (AIG, Fortune 500), then $700 billion to TARP. This was part of a much broader cloth, and it's helpful when people think about it in that context.

Do you think Lehman's managers understood the risks they faced better than Lehman's shareholders were able to understand them?

I don't know about the Lehman situation, so I won't comment on that specifically.

But we've seen exactly what you say -- that the identification and management of risk were not what they needed to be at the management level or the board level or the investor level. So among the wide array of things investors are talking about is how they could get greater visibility into how risks are identified and managed.

What Lehman did, moving assets around at the end of the quarter, is called window-dressing. It's legal. Financial firms have done it for decades. Now the SEC and the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission are investigating it. Should it be forbidden?

All organizations -- financial firms and others -- manage their balance sheets. I don't think managing the balance sheet by itself is window-dressing. What's important is to make sure investors have a proper view of the leverage of an organization. The repo transactions at Lehman -- and again, the accounting for them wasn't challenged -- would have changed the leverage from something like 31 times to 32 times. Lehman would have remained the third-highest-leveraged bank.

To what extent is it the auditor's responsibility to make clear to the outside world what the real situation of an organization is?

We have a proactive responsibility to make sure that we comply with auditing standards and that the clients we serve are complying with the requisite accounting standards. So the first and most important responsibility is to act diligently and professionally in compliance with standards, and have the clients do the same.

Where the application of those standards would result in something that is not, in European parlance, true and fair, then we ought to figure out how to discuss this with regulators, discuss this in a more open way with audit committees, and figure out the next step to take.

What you're seeing today is the regulatory community wanting to figure out how and whether the auditor should work more closely with prudential supervisors. The FRC [Financial Reporting Council] and FSA [Financial Services Authority] in Britain put out a white paper talking specifically about that. What role should auditors who serve financial institutions have in talking to the equivalent of the Fed, the OCC [Office of the Comptroller of the Currency], and the bank regulators? That's a discussion that's going to take place over the next year.

Would it be fair to say that the crisis was caused in part by some financial firms doing misleading things that were within the rules?

I don't know that it would be fair to say they were doing misleading things. I think that at the end of the day, there were a lot of really poor business decisions that came home to roost. In the first instance, it was making loans, largely on real estate, that were not properly underwritten -- no due diligence was done on the borrower -- with an unrealistic expectation that real estate values would always be steadily going up, and it didn't really matter if the borrower could pay back because the collateral value would keep the bank whole.

I wouldn't characterize that as misleading. I'd characterize that as a bad business decision when the circumstances changed dramatically, just as many organizations made the bad business decision of buying into the securitized and derivative assets off of those loans. I think that's really what we're seeing.

Ernst & Young has long been a big booster of entrepreneurship, giving awards for it for years. Will a new 2,300-page financial regulation law like Dodd-Frank be good or bad for U.S. entrepreneurs?

I'm worried that it's not going to help. Entrepreneurs are central to the job growth we need so badly. One of my fears in this recovery is that the entrepreneur stays on the sideline. I saw some studies very recently showing that in the recent quarter there was the lowest number of new business starts we've seen in forever.

What accounts for that?

What I hear from the marketplace in the U.S. is that it's a lot of regulatory uncertainty. You saw health care being juggled for a long time, financial reg reform juggled, cap and trade, tax policy, labor law policy, card check, the overall debt situation -- all these things create an environment where risk taking is largely discouraged.

You mention tax policy -- how do you rate the Obama administration on corporate tax policy, specifically its proposal to end the foreign tax credit?

U.S. corporate tax rates and policies are globally uncompetitive. If we end up making changes that would result in them being more uncompetitive, that's not a positive thing. We're one of the few countries in the OECD nations that have this tax on worldwide income. That is a page-one issue for all multinational businesses. We're also one of the few countries that in the last few years have not been reducing corporate rates, but instead are maintaining or increasing them.

What drives Ernst & Young's thinking are two big trends that in our opinion drive the world. One is the shift in capital we're seeing: West to East, North to South, developed to emerging. The other is the demographic shifts taking place. All the strategic actions we're taking as an organization are aligned with those. So we can't think about the U.S. in the absence of thinking about its place in the world.

What demographic shifts do you mean?

The people coming out of universities, the workforce of tomorrow, will be much more diverse around gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation. The generational differences are profound. Any organization that wants to win in the future has to be truly global in its outlook and has to embrace differences like you've never seen.

A lot of employers in every industry would love to know what you've found about what today's best young people want when they're choosing an employer.

We did some research on this not long ago, and it identified some things and burst some myths. The top three things young people cared about were actually the same as for people my age: learning and growth opportunities, being in an organization that they trust and that offers a career path, and having flexibility in their lives. What was very clear is that the people of today want a little more control over their lives. They don't want to be told, "Come in at 8:30, leave at six." They want to be treated like professionals from day one, trusted to get the job done. And they clearly communicate in different ways. Social media are vitally important to them, so we utilize that a lot. ![]()

| Company | Price | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ford Motor Co | 8.29 | 0.05 | 0.61% |

| Advanced Micro Devic... | 54.59 | 0.70 | 1.30% |

| Cisco Systems Inc | 47.49 | -2.44 | -4.89% |

| General Electric Co | 13.00 | -0.16 | -1.22% |

| Kraft Heinz Co | 27.84 | -2.20 | -7.32% |

| Index | Last | Change | % Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dow | 32,627.97 | -234.33 | -0.71% |

| Nasdaq | 13,215.24 | 99.07 | 0.76% |

| S&P 500 | 3,913.10 | -2.36 | -0.06% |

| Treasuries | 1.73 | 0.00 | 0.12% |

|

Bankrupt toy retailer tells bankruptcy court it is looking at possibly reviving the Toys 'R' Us and Babies 'R' Us brands. More |

Land O'Lakes CEO Beth Ford charts her career path, from her first job to becoming the first openly gay CEO at a Fortune 500 company in an interview with CNN's Boss Files. More |

Honda and General Motors are creating a new generation of fully autonomous vehicles. More |

In 1998, Ntsiki Biyela won a scholarship to study wine making. Now she's about to launch her own brand. More |

Whether you hedge inflation or look for a return that outpaces inflation, here's how to prepare. More |