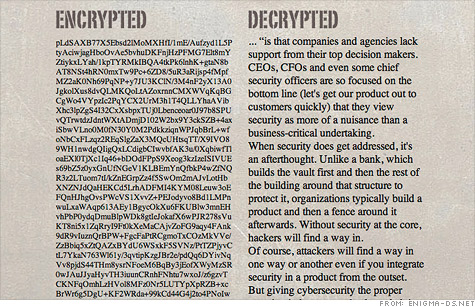

The creators of Engima-DS, pictured above, say they've created an unhackable code -- but experts say good encryption is the least of our cybersecurity problems.

NEW YORK (CNNMoney) -- Every day the news hits of another company, website or long list of credit cards that's been hacked. But what if there was a foolproof technology to fend off cyberattackers by keeping secret information secret?

Would an unhackable encryption algorithm do the trick?

That's what a father and son team from Calgary, Alberta, say they've created. For the past several years, cryptographic hobbyists Robert and Frederik Kleiner have been working to develop Enigma-DS, an encryption code that they claim cannot be broken.

Rather than encrypt a bit of text letter by letter (A becomes Q, B becomes H, etc.), Enigma-DS converts text into code based on language, sentence structure and words. For example, the word "rose" could become "wp76546hj!lldrk," but "rise" might become "aq!@#Qh!21mb."

A unique key is generated for every encoded item. Even if someone were able to discover the key to unlock and decrypt one file, others would remain unaffected by the breach, the Kleiners say.

They're so sure of their code's security that the Kleiners ran a contest this summer offering $100,000 to anyone who could crack it. No one broke the code during the two months that the little-publicized competition ran.

They even challenged the National Security Agency to break it, which declined to comment beyond saying the agency welcomes such submissions.

If you're skeptical, so are cryptography and cybersecurity experts. Encryption, they say, is not the weakest link in the security chain. People are.

Security professionals already use cryptography that, for all intents and purposes, cannot be cracked. Tools like one-time pads, which generate new code-unlocking keys for each encryption, or encryption methods like the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) are so complex that they could not be broken by modern supercomputers in our lifetime.

But human beings, unfortunately, just aren't that dependable.

"The problem isn't encryption, the problem is people using weak passwords or the same passwords on 100 different places," said Chuck Easttom, a cybersecurity trainer at EC-Council's Center of Advanced Security Training. "The past six months have been replete with hacking stories, and not one has been because an encryption was broken."

For instance, RSA, a division of EMC Corp. (EMC, Fortune 500) and one of the world's preeminent security and encryption companies, was hacked in March, rendering many of its popular SecurID tags less secure. But RSA's encryption wasn't hacked -- attackers simply sent phishing e-mails with the subject line "2011 Recruitment Plan" to RSA employees. One worker opened the Excel file attached to the e-mail, which set loose a program letting the attacker control the employee's PC. From there, the attackers roamed through RSA's systems.

The cybersecurity landscape can change in an eyeblink -- as RSA found out.

"We're implementing techniques that just a couple of weeks ago I thought were in the realm of long-term roadmaps," Uri Rivner, RSA's head of new technologies for consumer identity protection, wrote in a blog post soon after.

Even if we don't need better encryption now, we may need it soon -- perhaps even within the next decade or two.

Mathematicians say that the theories of quantum mechanics could eventually be applied to decryption, giving computers the ability to crack in seconds a code that a supercomputer today would take 150 years to crack.

"Virtually any encryption program can be broken, it's just a matter of time," said Patrick Carroll, CEO of security firm ValidSoft Limited. "Current models will stand the test of time for the foreseeable future, because modern resources can't break them quickly enough. But quantum theory is probably a decade or two away from commercialization."

Still, even experts who applaud the attempt say Enigma-DS raises two big red flags: no encryption algorithm was made available, and sufficient time was not given to test the code.

Analysts note that encryption algorithms are generally released to the public so that they can be tested for security. They also say peer reviews typically last several years. The 75 days Enigma-DS offered is not sufficient.

Uncrackable code claims are common, according to Brian Tokuyoshi, a product manager on Symantec's encryption team. Cyptography discussion groups are filled with them.

"There is a difference between unbreakable and unsolved," Tokuyoshi said. "There is a long list of famous unsolved encrypted messages."

One of the best-known is viewed daily by some of America's finest cryptographic minds. A sculpture called "Kryptos," which sits at the Central Intelligence Agency's headquarters, features four encoded messages. Three have been deciphered, but the fourth still remains a mystery 20 years after the artwork's debut.

Typically, "unbreakable codes" remain unsolved if the sample encoded message is so short that cryptographers cannot do sufficient analysis on it or if the randomized key is known only to the author.

Both are true of Enigma-DS: Robert Kleiner says he is unwilling to share his algorithm, maintaining that it's intellectual property and the key to his business. The encoded text offered on his website is also relatively short.

Yet the Kleiners say they are willing to go through just about any test apart from divulging the algorithm to prove their concept. They say they will demonstrate it live, and they offered to provide analysts with a clear text to help them reverse-engineer the code.

"If you think it's too good to be true, then hack us!" Robert Kleiner said.

Some analysts we spoke to tried -- and failed. But that doesn't in itself indicate that it's unbreakable. A preliminary assessment of the code by EC-Council's Easttom, for instance, revealed that it failed every test of randomness he threw at it. Randomness is one of the key elements cryptographers look to when approving new encryption methods.

Multiple cryptography experts called Enigma-DS a publicity stunt. Alex Gostev, chief security expert at Kaspersky Labs, dismissed it "snake-oil cryptography," citing the group's short peer review and desire to sell its technology.

Robert Kleiner, in turn, accused security professionals of having ulterior motives. In his view, an unhackable code could put them out of business.

"They're so stinkin' lazy," he said. "We always hear security professionals lament that there is no such thing as an unhackable code; now someone claims they have it and they immediately dismiss it. These security guys are a bunch of hypocrites."

So is Enigma-DS truly an unhackable code? Without sufficient testing, we may never be sure.

But as cybercrime escalates, the need for creative approaches -- even ones that sound crazy -- is also growing. ![]()