It might seem antiquated to use hawks and peregrines instead of guns to kill ducks, quail, and rabbits, but 4,500 falconers are licensed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the North American Falconers Association (n-a-f-a.org) says its membership is on the rise. A sport that originated some 2,000 years B.C. as a way to hunt for food - Genghis Khan helped feed his Mongol army with whatever his birds brought home - falconry became an elite sport during the Middle Ages, practiced by Arabian princes and British royalty. (Mary Queen of Scots was allowed to fly a bird from her window during imprisonment.)

Falconry demonstrations recently added by luxury resorts such as the Greenbrier in White Sulphur Springs, W.Va., have spurred the sport's growth. But these tours feature little interaction with birds - falconers lead tourists on nature walks, showing how hawks take off and land from their gloved wrists. Tigan's course, which costs $565 and includes breakfast, lunch and books, teaches students how to feed and care for a hunting bird and incorporates lessons on raptor biology, proper housing and training techniques demonstrated in the field.

I pull into Tigan's gravel driveway, off a remote country road some 55 miles northeast of Sacramento. Tigan's school is run out of his home, which he shares with Kate Marden, his business partner, fellow falconer, and wife. In a steady rain, the countryside seems quiet and barren. And then I see them: five soggy birds on perches, their eyes glaring at me from 100 yards away.

As I walk into Tigan's living room turned classroom, Cailleach, a five-pound Eurasian eagle owl, screeches. I'm taken aback by my fellow students: two teenagers (by law, a falconer can begin to apprentice at age 14), a real estate developer from Los Angeles, a retail executive from New York City, and two falcons. For the next three days the birds are always with us, sitting quietly on AstroTurf-covered perches and pooping inches from our knuckles as we take notes.

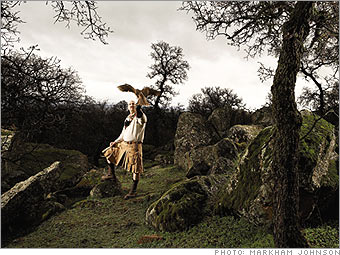

It's hard to say which is the more unusual sight: a falcon in the living room or Tigan himself. Six feet five inches tall and bald, Tigan greets me wearing a Blue-tooth earpiece and khaki kilt. A former Coast Guard aviator and founder of the Alaska Raptor Rehabilitation Center (alaskaraptor.org) in Sitka, Tigan became a falconer about 25 years ago after reading "My Side of the Mountain," Jean Craighead George's coming-of-age novel about a boy who flees the city for the wilderness, adopting a falcon along the way. Despite Tigan's stature, his tone is quiet and earnest toward his birds and students. "Hunting with a gun never had much appeal to me," he says. "Forming a relationship with a creature that remains somewhat wild - that appeals to me."