The green sailor Bill Joy was once called "the Edison of the Internet." Now he's building his $50 million dream boat - an eco-friendly, 190-foot superyacht named Ethereal.

(Fortune Magazine) -- Bill Joy is wearing bright-red sneakers and a boyish grin that belies his 52 years. Although dusk has settled over the Netherlands' Royal Huisman shipyard and hunger pangs are surely gripping the locals on his project team, he shows no sign of letting up. The co-founder of Sun Microsystems and the man once dubbed "the Edison of the Internet" is building his dream boat, Ethereal, and the team is into its 13th meeting in the pursuit of perfection. Nautical hardware has become the software guru's passion, and today he has already pondered such exotica as the dog locks on the deck hatches. Now the topic is light switches and motion detectors for the cabins. Don't laugh. Wind will power his 190-foot, $50 million superyacht through the waves, but to produce the electricity that will drive winches and navigation systems, run the A/C, and cool the wine, she needs generators. And that means noise and vibration, which negates the whole point of a sailboat.

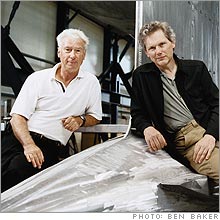

So Ethereal will also have batteries to enable her to cut the generators and run silent for long periods - a bit like the U-boats of yesteryear and a first for yachts this size. Joy wants to ensure that those pesky lights in the four guest cabins, two salons, and owner's suite (which will contain an office, a sauna, and a Jacuzzi) consume as little electricity as possible. More important, he wants Ethereal to be the most efficient, eco-friendly boat afloat - an ambassador for the "green tech" he and his new venture capitalist partners at Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers are championing. The right man for the job Some of the team offer suggestions, while others take notes. One man listens attentively, even though he's not responsible for Ethereal's innards. He is New Zealander Ron Holland, 59, a world-class yachtsman and one of the leading naval architects of his generation, who has designed boats for the likes of Prince Rainier of Monaco and media mogul Rupert Murdoch. Holland has already done his bit for the yacht's efficiency by designing a hull and rigging that will allow her to slip through the water at speeds most motorized superyachts could not match - and without consuming a drop of fuel. Joy concedes that he second-guessed Holland's initial hull design. "Ron drew it, and we tried longer and shorter and other things," he recalls. "In the end we came back to what he had done in the beginning - in other words, his intuitive feel for what was going to work turned out to be correct. We did a lot of simulations and tank testing to go in a big circle." A newcomer to the sailing scene - he has never owned even a dinghy - Joy has discovered what the yachting fraternity has known for a long time: Yacht design is as much an art as a science, and if you want a boat that will sail like the wind, then get Holland to draw it. Largely self-taught - he began his career 40 years ago as an apprentice in a New Zealand boat yard - Holland has been drawing winners since 1973, when he skippered his own design, the 24-foot Eygthene, to victory in the world Quarter Ton Cup. Commissions soon followed from leading yachtsmen, including the British Prime Minister, Edward Heath, who spearheaded England's 1979 Admiral's Cup challenge in the Holland-designed Morning Cloud. Though built for cruising, not racing, Ethereal will inherit the Holland performance pedigree, with a likely top speed of about 18 knots - fleet enough to keep up with the tea clippers of yore. Integrating 'green tech' But if Joy is learning about yacht design from Holland, the latter is getting a crash course in what Joy calls an "integrative design process." Translation: Joy is encouraging his team to think of Ethereal not just as a yacht but as a self-contained community that must provide vital amenities like power and fresh water while at the same time dealing with waste products like heat, noise, sewage, and trash. And he is pushing for simple, elegant solutions that deal with problems by designing them out of the boat. Those cabin lights, for example. Conventional incandescent lights produce huge amounts of heat. Replacing them with cooler light-emitting diodes, an increasingly popular feature on boats, permits a smaller air-conditioning system that saves weight, space, and energy. An innovative lithium-ion battery bank will smooth out fluctuations in electric demand, allowing for more efficient use of smaller generators. And when the wind dies, Ethereal's propellers will be driven by a unique hybrid of diesel and electric motors that will move the yacht, power the household systems, and recharge the batteries, all at the same time. "Our approach is to think about demand first and then supply," says Joy, explaining that if you can reduce the former, you need less of the latter. "You can never capture all the efficiencies," he concedes, but that won't stop him from trying to make Ethereal what he calls a "continuing instrumented laboratory" for the green tech that has become his new passion. "For every technology that we use, there will be ten we don't but will now know about." And if one comes along - like an efficient fuel cell that can replace or supplement noisy diesel generators - it will be retrofitted to the boat. New 'wind in the sails' for yacht design "It's an approach that's long overdue and should have a big impact on future yacht design," says Holland, who is no stranger to innovation. In his studio overlooking the small Irish sailing port of Kinsale are paintings and drawings of superyachts - those longer than 100 feet - that testify to his ability to push design boundaries. They include Whirlwind XII, launched in 1986, which marked Holland's transition from racing boats to cruisers and was the first postwar, single-mast boat to break the 100-foot barrier. "Ron Holland was the pioneer of modern superyachts," says Newport, R.I., yacht broker and former professional skipper Hank Halsted. "He was the guy who early on understood how to make these huge ships handle like real sailboats. If they didn't, there would be no super-sailing-yacht business today." According to Halsted, who helps organize the two superyacht regattas that take place each year at Newport and St. Barts, the owners of giant sailboats, unlike those who drive the motorized variety, are turned on by the closer contact with the ocean and the elements their boats allow. Although their yachts lack nothing in the way of comfort and luxury, says Halsted, "they are there to be sailed rather than tied up in some chic harbor and admired." While some yacht owners have been known to hang Old Masters in their boats, Ethereal will have a simpler, laid-back look, serving, Joy explains, as "the perfect mobile gathering place for family and friends." But the real reason he is spending $40 million is that he finds sailboats romantic. "Nothing beats the motion of a sailboat," he says, "the feel of the wind, or the rocking at anchor with the sound of the sea outside." Adds Holland: "It's something in the soul. Sailors can imagine themselves following in the wake of the great seafarers like Magellan, Vasco da Gama, and Cook." Size matters Superyachts have been around for some time. The classic J-Class yachts of the early 20th century were supersized - Shamrock V, Thomas Lipton's last challenger for the America's Cup in 1930, measured 120 feet - but they also required a crew of 40 or more to sail them. The breakthrough to the modern superyacht came when Holland and Royal Huisman collaborated on Whirlwind XII. Before that, no one believed it was possible to build a super-sloop that could be sailed like a smaller boat because the forces at work on the sails and hull were too great. Holland was the first to take up the challenge and harness new technologies to make Whirlwind XII as easy to sail as a dinghy. "We replaced muscle power with hydraulics and electrical winches to raise and furl huge sails and sheet them home at the press of a button," Holland explains. With a length of 247 feet, Mirabella V, the Holland-designed sloop built three years ago for former Avis tycoon Joe Vittoria, is the largest single-mast yacht on the planet, with the world's biggest sails and a mast that would need to be shaved by 75 feet to pass under San Francisco's Golden Gate Bridge. But her 12-strong crew numbers only five sailors, including the skipper. Another driving force behind the superyacht surge has been a tidal wave of money that has expanded the ranks of billionaires to about 700 worldwide over the past decade. For some the superyacht has become a way of flaunting new wealth. "There's testosterone at work, for sure," says Jill Bobrow, editor of ShowBoats International, a magazine that closely monitors the superyacht industry. "But these boats are also about luxury, security, and privacy, about separating yourself from the rest of the world while, paradoxically, remaining in touch through modern communications." The result: ever larger and more expensive ships, most of them motorized. Ships on steroids include a 525-footer belonging to Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid al-Maktoum, the ruler of Dubai, who named his boat after his emirate; Rising Sun, whose owner, Oracle founder Larry Ellison, stretched the original design length to 452 feet in order to outdo Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen's Octopus (414 feet); and Pelorus (377 feet), the largest of the three mega-yachts belonging to Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich. His fleet also includes Le Grand Bleu (370 feet) and Ecstasea (282 feet). European shipyards have enjoyed a near monopoly when it comes to building these leviathans, which cost roughly $1 million a yard (excluding such extras as helicopters and the miniature submarine carried by Pelorus for emergency escape). It's not all easy sailing for the superyacht crowd. Industry specialists point to a shortage of competent crew and a dearth of berths for the largest ships. But these constraints haven't dented demand. According to ShowBoats International, this year saw the order book for luxury yachts (defined as vessels longer than 80 feet) grow to 688 boats either under construction or under contract, compared with 651 in 2005. It would seem that even as the boating billionaires have succumbed to the "grow, grow, grow your boat" mantra, the more discerning among the mega-rich are sending out the message that size doesn't matter (well, not too much), but sail does. Earlier this year Rosehearty (184 feet), a high-performance ketch designed by Holland in partnership with Italian shipbuilder Perini Navi, was delivered to Murdoch in time for him to gatecrash the St. Barts superyacht regatta. Then came Parsifal III (176.5 feet), a Perini-Holland collaboration for Danish coffee-machine magnates Kim and Nina Vibe-Petersen, which was named sailing superyacht of the year in April at Boat International magazine's 2006 World Superyacht awards. These two thoroughbreds join a fleet of Holland-designed boats that include Stalca (a mere 83.6 feet), built for the late Prince Rainier of Monaco in 1985; Juliet (143 feet), the boat that inspired Joy to build Ethereal after he sailed on her with friend and owner Bruce Katz, founder of Rockport Shoes; and Felicita West (210 feet), launched in 2002, the world's largest aluminum-hulled yacht - until the commissioning later this year of the 295-foot schooner Eos. Holland is also designing a powerboat, the Marco Polo, a 148-foot, long-range expedition yacht now being built in China, which many predict will replace Europe as the next yacht-building center and a major source of new clients. Intended as the first of a series, Marco Polo is designed for a growing breed of adventurous boat owners who want to escape the traditional - and increasingly crowded - cruising grounds and explore Antarctic waters and the like. But sailing boats will remain Holland's true calling, and it will be another year or more before his masterpiece, Ethereal, is ready for christening. In the meantime, there are designs to mull and efficiencies to be captured at Royal Huisman. Here, at day's end, the discussion about lights is finally drawing to a close. But never mind. Tomorrow's agenda includes such items as ironing machines, door magnets, and things for keeping portholes open. Oh, joy! From the September 4, 2006 issue

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||