|

The new face of labor There's a reason organized labor is suddenly showing signs of life. His name is Andy Stern. He's like no union boss you've ever seen.

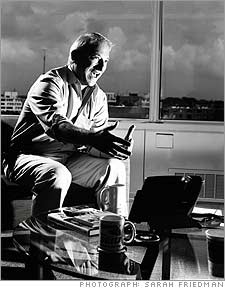

(Fortune Magazine) -- In a sunlit office overlooking Dupont Circle in Washington, D.C., union leader Andrew Stern, 55, is sipping coffee and holding a midmorning meeting with a few top aides. The subject is a study on the future of government - a topic of deep interest since roughly half the 1.8 million members of his Service Employees International Union (SEIU) work in the public sector. It's solid leader-as-visionary stuff but fairly predictable until, as things wind to a close, Stern suddenly kicks it up. Way up. "One last thing," he says. "I really think it's critical you reach out to hear from Grover Norquist or Stephen Moore," referring to two influential Republican advocates of the slash-taxes-and-starve-the-government approach to fiscal policy. "You need to understand what they think is core and what might be privatized."

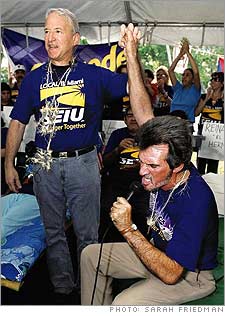

Stern pauses and looks around the room. "We all know what will happen if we talk only among ourselves. We'll end up wanting to preserve everything. And that just ensures we'll be fighting a war of attrition, where it's all about 'How do we hang on to these 100 jobs?' " People start to nod, and he breaks into a wide grin. "Nobody wins a war of attrition. What we need to figure out is ... how we can go on the offensive." That's not just the coffee talking. While most labor generals have spent their careers waging the Long Retreat - the percentage of U.S. workers who belong to a union has fallen from a third in 1950 to barely 12 percent today - Stern stands out as a leader who knows how to attack. And win. A man of action Since he took charge in 1996, the SEIU has become the country's largest and fastest-growing union, adding more than 800,000 members, many of them in low-wage, hard-to-organize sectors such as security, janitorial services and home health care. He did that by cutting headquarters staff, dedicating most of his budget to field organizers and consolidating some 170 balkanized locals to strengthen their negotiating clout. More broadly, you could argue that Stern is almost single-handedly reinvigorating a national labor movement. Maybe you've noticed California's recent decision to raise its minimum wage? Or the grass-roots campaigns that have put Wal-Mart (Charts) on the defensive over its pay and health benefits? Or this summer's huge and noisy pro-immigration rallies in cities like Los Angeles and Washington, D.C.? Stern and the SEIU's manpower and money were behind them all. His boldest move came last year when, after failing to persuade AFL-CIO head John Sweeney to adopt his aggressive playbook, he walked out. Joined first by the Teamsters and soon after by five other like-minded union heads, Stern formed Change to Win - the country's first new labor federation in 50 years. With more than six million workers, it's already a serious rival to the nine million workers (in 53 unions) who remain in the AFL-CIO. Though that shocking split continues to outrage many fellow labor bosses, Stern insists he had no choice. "We're going through the most profound, the most transformative economic revolution any generation has ever experienced," he says. "You either change to make history, or stick to the status quo and become history." Stern's efforts to modernize the way unions work go well beyond his willingness to live on his Treo or blog regularly on the oh-so-happening Huffington Post. He has merged and purged dozens of the SEIU's union locals, some of them notoriously corrupt. And he believes labor needs a "bigger footprint" than it can ever gain by simply delivering a good deal for its own members. That's why, though the SEIU has no stake in organizing workers at Wal-Mart, Stern nonetheless cooked up the idea for the grass-roots pressure group Wal-Mart Watch, and is now spending nearly $4 million a year to support it. "If your goal is to make work pay for everyone," he says, "you can't ignore what's happening at the nation's largest employer." Politics makes strange bedfellows And then there are the unusual types he's lately taken up with, like Newt Gingrich. In his new book, "A Country That Works: Getting America Back on Track" - part memoir, part manifesto - Stern admits that a decade ago he considered Newt the "devil incarnate." But after they met, he writes, he concluded that Gingrich's ideas - especially about how labor needs to adapt to a knowledge and service economy - "reinforced much of my own thinking." (Gingrich declined to be interviewed.) Stern also studies the Republicans because they know how to win. He raised eyebrows when he invited Steve Moore, co-founder of the Club for Growth - which often goes after Republican apostates from its anti-tax stand - to address his union. "I thought, The guy has a couple of things going for him," says Stern. "One, he actually believes in something, and two, he scares the hell out of folks." Despite spending $65 million trying to defeat George Bush in 2004, far outstripping any other union's spending, Stern insists he has zero interest in perpetuating labor's role as the loyal financier of the Democratic Party. Instead, he's forming a new PAC, called They Work for Us. Modeled on the Club for Growth, it will target Democrats who get elected after 2006 pledging to support SEIU's economic agenda and then fail to deliver. "If that happens, we'll unelect them," says Stern. Everybody doesn't love Andy. His eagerness to question labor's orthodoxies offends the old guard. Dismissing his rival as "a rather small peacock," machinists' union head Tom Buffenbarger accused Stern in the New York Times Magazine last year of "trying to corporatize the labor movement." On the right, some conservatives like David Horowitz and Richard Poe, authors of a new book, "The Shadow Party," view Stern as a "radical" bent on using his power as a Democratic "cash cow" to yank the party to the left. Many CEOs and pro-business types simply don't want to talk about him - they have little to gain by praising a union leader who's actually proving effective, and less by crossing him publicly. But the few who will speak on the record say that his efforts to think differently and find some rare bipartisan ground are the real deal. "Andy is absolutely straight-up," says David Lawrence, the former head of Kaiser Permanente, with whom Stern settled a bitter, long-running labor dispute in 1997. "He's neither defensive nor paranoid and takes a pragmatic approach to solving problems." "He's a maverick with his own mind and his own way of running things," says California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, who invited Stern to be one of a handful of speakers at a star-studded health-care conclave he hosted this summer. "Andy's a breath of fresh air," agrees Tom Donohue, president of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which is girding for a fight in the next Congress over the rules governing the recognition of unions. Now Stern is taking on his biggest challenge yet. In July he issued a manifesto on the op-ed page of the Wall Street Journal calling for an alternative to employer-based health coverage. Stern also sent a letter to every Fortune 500 CEO calling on them to join him in devising a new and better national system. "The old idea that business and labor can't work together for the common good is as outdated as lifetime jobs," he declared in a fine rhetorical flourish. Never mind that Washington handicappers give Stern's assault about the same odds of success as Pickett's charge up Cemetery Ridge. He just shrugs: "You have to stumble around - and hope you stumble forward." Cleaning up the SEIU "That's the vault I told you about," says Andy Stern. It sure is. I am staring at a huge stainless-steel door that looks like something Scrooge McDuck would order up to protect his stash from the Beagle Boys. Around the corner are other jaw-dropping touches: a personal elevator, a luxurious marbled bathroom and a vast kitchen. "Never used," he volunteers. "No one was allowed up here except Gus's assistant." "Here" is a soon-to-be-renovated expanse of the 23rd floor of 101 Avenue of the Americas. "Gus" is a son of lower Manhattan named Gus Bevona, who from this place long ruled SEIU local 32BJ, which represents New York City's doormen, janitors and security guards. (John Sweeney picked Bevona to succeed him as head of the local in 1980, when Sweeney became the SEIU's national boss; Bevona continued to pay Sweeney $70,000 to $80,000 a year in "consulting fees" on top of his national salary.) In exchange for delivering his members excellent salaries and benefits, Bevona felt entitled to construct his penthouse Xanadu with river views and pay himself north of $400,000 a year - reportedly the highest salary of any union head. (Stern's salary last year: $230,000.) His was an extreme case of a corrupt management model all too typical in many old-style unions. Bevona's reign ended in 1999 when Stern asserted the national union's right to put the local into trusteeship and tossed Gus from his pleasure dome. "This was slaying the dragon," he says. Over time, Stern adds, he has had to trustee more than 40 SEIU locals. "Everywhere I go there's one big fight," he told a reporter from the Philadelphia Inquirer early last year. It was a throwaway line that rings true. Stern spent his early years leading long and bitter civil service strikes in Pennsylvania. (He grew up Jewish and middle class in West Orange, N.J., where his father was a lawyer; he launched his union career after graduating from the University of Pennsylvania and becoming a social worker.) In 1984, Sweeney recruited him to be the SEIU's chief organizer, which required traveling around the country banging heads with employers. In 1995, Stern helped lead the insurrection that forced out longtime AFL-CIO head Lane Kirkland and put Sweeney in his place. Early the next year, when Sweeney tried to install a hand-picked successor as the SEIU's head, Stern announced his own candidacy. He was promptly fired and escorted from his office. So he took to the road in a six-week insurgency that ultimately led to his election as president. Life and death decisions Some of Stern's relentless intensity is temperament, some of it has been shaped by life - and death. In 2002, Stern's 13-year-old daughter Cassie, who had always been unusually tiny and suffered from poor muscle tone and scoliosis, died in his arms after complications from surgery. His marriage unraveled, and he moved into a sparsely furnished apartment with Cassie's older brother, Matt, who this fall started college in South Florida. In his book, Stern writes movingly about how the pain of losing his daughter and the memory of her courage reinforced his determination to "find his voice to do what's right." It's not something he goes on about in person, though he doesn't shy from the subject either. In hours of interviews, he brought Cassie up once, recalling how he dealt with the "character assassination" that greeted his decision to leave the AFL-CIO: "My daughter's death was one of those life-changing things where you say, 'All right, nothing can hurt me more than I've been hurt, so go for it.'" Rallying the troops "We want to make labor costs resemble electricity," Stern likes to say. "We want employers to compete on how they use capital, innovation, technology and management creativity - not on how they screw their workers." The basic playbook was developed by Stern and the SEIU more than 15 years ago to organize janitors in Los Angeles. Rather than pressure the weakest individual employers to raise salaries and benefits - which simply makes the unionized workers uncompetitive with non-union wages - they try to organize the entire industry. The device of choice is what's called a trigger agreement: If employers agree not to interfere with the SEIU's organizing efforts, it promises not to begin collective bargaining until a clear majority of the market has recognized the union. Using this approach in New Jersey, the SEIU swung from having almost no presence five years ago to representing more than 6,000 janitors, whose pay nearly doubled from the minimum wage, to more than $11 an hour. Late in 2005 in Houston, the SEIU hit its trigger and formed a local with 5,300 janitors, the most successful private-sector organizing drive in the Sunbelt in years. (Talks on wages and benefits are still ongoing.) Nationally over the past decade the SEIU has moved from having a shrinking membership in property services to adding 100,000 members and negotiating master agreements that cover between 60 and 90 percent of the market, depending on the city. In building membership, Stern prefers to use the "power of persuasion." Says he: "The labor movement has proved that going out on strike at the first sign of trouble is a losing strategy." On the persuasion front he can point to numerous successful partnerships. The SEIU's peace pact with Kaiser Permanente, for example, has delivered tens of millions of dollars in cost savings to the company by reducing the time it takes to change shifts and finding other efficiencies. With nursing home operators in many states, SEIU offers to use its clout with legislatures, which often fund such operations, in exchange for union recognition. But if companies balk, Stern doesn't hesitate to rely on the "persuasion of power" - ready-for-prime-time picket lines, say, or creative civil disobedience. In its latest drive to organize Los Angeles and New York City security guards, a majority of whom are black, SEIU has begun reaching out to black church leaders for their support in galvanizing what Stern calls "a broader social justice movement." Thinking globally Stern has also been in the vanguard pressing unions to start thinking globally. "Most of us considered international union meetings little more than an exercise in Tourism 101," admits Bruce Raynor, president of Unite Here, which represents hospitality and garment workers and is part of Change to Win. Recently, for example, Raynor's Unite Here partnered with France's largest union, the CGT, which helped it organize 900 workers in Indianapolis by putting pressure back home on their employer, French conglomerate PPR. Stern himself is partnering with the TGWU, England's giant transport union, to assist its push to organize janitors in London. In exchange the TGWU is helping him raise the heat on a British bus company that he feels has been slow to recognize unions in its American operations. "We all increasingly deal with the same group of multinational employers," says Stern. "By working together we may be able to use the global economy to our advantage." A big wild card is China. In 2002, when Stern made his first trip there, most American union heads still considered it "heresy," as he puts it, to meet with the government-controlled lapdog group, the All China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU). "But I believe that during historical moments of transition," he says, "people transform themselves to represent the interests of their constituents." Four years, four more visits, and billions of dollars of foreign investment later, he sees signs that change is on the way. Recently the ACFTU forced Wal-Mart to allow it to organize workers in its mainland stores, and Stern hopes to send observers soon to watch the process. How deep can such global alliances go? "There are no models," he admits. "Still, it's amazing how change happens sometimes. Like Newt Gingrich says, 'You just have to plan back from victory.'" Ah. There he goes again. "How can America compete in a global economy when we're the only country that puts the price of health care on the price of our products?" Jacket off, sleeves of his purple shirt rolled up - Stern declared purple the SEIU's "brand" a few years back - he is shouting out to a largely black and Latino crowd at a pre-Labor Day rally at St. Vincent's Hospital in Manhattan. ("Mmm-huh.... That's right," mutter the women sitting beside me.) "That's why I wrote to the Fortune 500 CEOs and said, 'Wake up, guys! Where's your leadership?' " ("Mmm-huh, yes.") "And here's the amazing thing. All these people started writing back. I even heard from my favorite friends at Wal-Mart." (Laughter.) "You know, Lee Scott, the CEO of Wal-Mart, was on that Charlie Rose interview show, and he said, 'Business and labor have to work together on health care.' I thought he couldn't get those words out of his mouth!" (Big laughter.) Mediating labor and business It's great political theater, and it's hard to quarrel with Stern's indictment of the current system's shortcomings - the soaring costs, the declining coverage, the unique way company-based health care hampers American competitiveness. Safeway (Charts) CEO Steve Burd told a U.S. Chamber of Commerce audience earlier this month, "I could have written" Stern's Wall Street Journal op-ed, adding, "He's talking about the same kinds of things I'm talking about." The logic behind reaching out to business is compelling as well. As Stern explained to the crowd at St.Vincent's, "One reason the Clinton plan failed back in 1994 is that it had no employer support; that's why we're spending so much time with our employers." In pushing for a new consensus, Stern, beyond briskly dismissing one pet Republican panacea - expanded health-savings accounts - has been careful to avoid drawing nonnegotiable lines around how a new deal might work. As long as there's a basic benefit for all, a choice of plans and doctors, and some kind of shared financing among business, government and individuals, he says, it's all up for grabs. "I believe he doesn't have a predetermined answer," says George Halvorsen, current head of Kaiser Permanente. "I've had several Fortune 500 CEOs ask me about Andy's letter, and I tell them, 'Absolutely talk to the guy. He is what he appears to be.'" And yet none of the big-company CEOs that Fortune contacted - and with whom Stern has met - were willing to speak with us. Is that because they don't think they'll agree with his solutions? Or are they uncomfortable about being seen making public policy whoopee with a fellow who plays such an active political role, buys his purple T-shirts by the hundred thousands and regularly send his troops to demonstrate noisily in the streets? Stern suspects that it's the latter. "We've become such a hot-button issue," he admits, suggesting that perhaps he needs "a third party, some neutral group like McKinsey," to convene a forum that could take this closeted conversation into the daylight. Even so, Stern remains relentlessly upbeat. "There's clearly a growing group of employers who think change in health care has to be fundamental and not incremental," he says. But he can't resist pointing out that folks who profess interest in his call "to reinvent the social contract" and "be more bipartisan" - and then cling to the sidelines - have to understand something he figured out long ago. "You can get rid of Uzis and still have handguns," he says. "You can work with Big Pharma and still criticize Big Pharma. You can go to a meeting with Arnold Schwarzenegger and still endorse Phil Angelides [the SEIU is backing the Governator's Democratic opponent in the upcoming election]. Life is complicated. But making it simple isn't dealing with reality." Inside the mind of Andy Stern Not every boss's office bookcase offers a window into his soul, but this one does. Stern is showing me his annotated-by-Newt copy of Alvin and Heidi Toffler's "Creating a New Civilization." (Gingrich wrote the foreword.) Next to it: a copy of "What Leaders Really Do," by Harvard management guru John Kotter. ("Kotter's good, but I've probably learned more from my own failures," Stern says.) On the shelf above is a bright-green bumper sticker asking, WHAT WOULD WELLSTONE DO? (as in Paul Wellstone, the Minnesota Democrat who led the party's progressive wing until he died in a plane crash in 2002). Life is indeed complicated. Alongside the stuff you'd expect - pictures of the kids and Stern with Presidents (Clinton and the current Bush) and would-have-been Presidents (Dean and Kerry) - are more telling souvenirs. There's a mock baseball card detailing the stats of one Mort "Trash Can" Zuckerman. It dates from the early '90s when the SEIU's janitors invaded the developer/publisher's annual Artists and Writers softball game in the Hamptons and handed out the cards to get attention during a labor dispute. There's a brass head of, yes, Gus Bevona, taken from a plaque that hung outside the House That Gus Built. (Also "the clicker he used to control his TV-spy cameras," Stern points out.) And over there on the bottom right, looking like fragments lifted from a Roman ruin, are six big iron letters taken from the SEIU's former headquarters that spell out ... of course, "AFL-CIO." With 20 minutes to spare before his next meeting, Stern is happy to share a few last thoughts about the challenges of tearing down the old and building a true "21st-century union." Yes, the problems of defending a shrinking number of high-wage manufacturing jobs are different from organizing the growing ranks of lower-wage service workers. But what they have in common is the need to confront industry with one union that can bargain hard and solve problems. "Look at the airlines," he says. "Thirteen unions are a recipe for infighting, constant concessions, and a downward wage spiral." The 53 AFL-CIO unions, he believes, should regroup into 20. And then he's off on even more futuristic topics: Could he form a for-profit, employee-owned company to provide temporary staff to his corporate partners in the nursing-home business? Does the SEIU need a new name without the word "union" in it? What can unions learn from evangelical megachurches about serving and delighting their congregations? Could he use text messaging to poll members faster? But time's up: An aide is giving us the cut sign. For his next meeting, an entrepreneur is dropping by to explain how he has developed greener ways to clean buildings. As I walk out, though, Stern is first telling the guy about My Life, a Web site that he hopes to launch in 2007 to begin providing his members the same broad range of services that AARP delivers to retired folks. And that's the image that lingers in my head as I stroll down the corridor: Andy Stern leaning forward in khaki pants and purple shirt, mind racing, mouth moving, talking, listening, brainstorming, questioning ... and always, always, looking for a way to stay on the offensive. _________________________ |

|