|

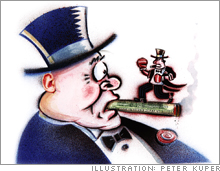

Revolt of the fairly rich Today's lower upper class is seething about the ultrawealthy.

(Fortune Magazine) -- Not long ago an investment banker worth millions told me that he wasn't in his line of work for the money. "If I was doing this for the money," he said, with no trace of irony, "I'd be at a hedge fund." What to say? Only on a small plot of real estate in lower Manhattan at the dawn of the 21st century could such a statement be remotely fathomable. That it is suggests how debauched our ruling class has become. The widening chasm between rich and poor may well threaten our democracy. Yet if that banker's lament staggers your brain as it did mine, you're on your way to seeing why America's income gap is arguably less likely to spark a retro fight between proletarians and capitalists than a war between what I call the "lower upper class" and the ultrarich.

Here's my outlandish theory: that economic resentment at the bottom of the top 1 percent of America's income distribution is the new wild card in public life. Ordinary workers won't rise up against ultras because they take it as given that "the rich get richer." But the hopes and dreams of today's educated class are based on the idea that market capitalism is a meritocracy. The unreachable success of the superrich shreds those dreams. "I've seen it in my research," says pollster Doug Schoen, who counsels Michael Bloomberg and Hillary Clinton, among others. "If you look at the lower part of the upper class or the upper part of the upper middle class, there's a great deal of frustration. These are people who assumed that their hard work and conventional 'success' would leave them with no worries. It's the type of rumbling that could lead to political volatility." Lower uppers are doctors, accountants, engineers, lawyers. At companies they're mostly executives above the rank of VP but below the CEO. Their comrades include well-fed members of the media (and even Fortune columnists who earn their living as consultants). Lower uppers are professionals who by dint of schooling, hard work and luck are living better than 99 percent of the humans who have ever walked the planet. They're also people who can't help but notice how many folks with credentials like theirs are living in Gatsby-esque splendor they'll never enjoy. This stings. If people no smarter or better than you are making ten or 50 or 100 million dollars in a single year while you're working yourself ragged to earn a million or two - or, God forbid, $400,000 - then something must be wrong. You can hear the fallout in conversations across the country. A New York-based market research guru - a well-to-do fellow who's built and sold his own firm - explodes in a rant about ultras bidding up real estate prices. A family doctor in Los Angeles with two kids shakes his head that between tuition and donations, ultras have raised the ante for private school slots to the point where he can't get his kids enrolled. A senior executive at a nationally known firm seethes at the idea of eliminating the estate tax; it is an ultra conspiracy, in his view, a reprehensible giveaway to people whose outsized lucre bears little relation to hard work. As one civic-minded lower-upper businessman told me, even his charity now feels insignificant: When buyout kings plunk down $1 million for a youth or arts group, his $20,000 contribution doesn't get him the right to co-chair a dinner, let alone a seat on the board. There's only so much of this a smart, vocal elite can take before the seams burst - and a bilious reaction against unmerited privilege starts oozing from every pore. Especially when it's clear to lower uppers that many ultras are reaping the rewards of rigged systems: CEOs who preside over tumbling stock prices, hedge fund managers who barely beat the market. It may seem far-fetched to think a revolt against extreme inequality will be led by posh professionals. But the conversations above suggest there's a potent political opening for a "comeuppance agenda." Eliot Spitzer, an ultra by birth (like F.D.R.), has shown the power of turning against the sleazy self-dealing of his class. Once Spitzer's crusades against greed sweep him into the New York governor's mansion next month, imitators may follow. Shame as a strategy to constrain avarice may come back into fashion. Like I said, it's just a theory. It could be sour grapes. But if I were in this for the money, I'd bet there was something to it. Matt Miller is a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress and the author of "The 2% Solution: Fixing America's Problems in Ways Liberals and Conservatives Can Love." |

|