Patagonia: Blueprint for green businessThe story of how Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard took his passion for the outdoors and turned it into an amazing business.(Fortune Magazine) -- "There is no business to be done on a dead planet." These words, a quotation from the legendary Sierra Club executive director David Brower, are the first thing you see when you walk into Patagonia headquarters in Ventura, Calif., and really, you can't miss them, given that they're etched into the front door.

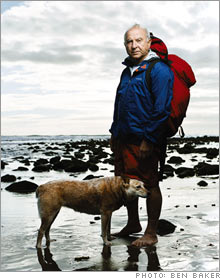

The next thing you see, posted on a whiteboard above the reception desk, is today's surf report: "3-5 feet, check water quality." Not too promising. Which is why most of the 350 employees who work at this campus, a block's worth of sunny, yellow Mission-style buildings, are actually in residence. Write "double overheads, offshore wind" on that board, however, and watch the place clear out. Freeform work environments have become common enough that barefoot employees, cavorting pets and organic chefs hardly merit a second glance. But Patagonia is no Web startup. It's a 35-year-old outdoor-clothing and equipment company. And yet, looking around at the bicycles, the surfboards, the solar panels, the Tibetan prayer flags, the shed full of convalescing owls and hawks, it's clear that you're not in traditional corporate-land, either. The place is all business, but it's business conducted upside down and inside out. Everything about it flies in the face of consultants' recommendations about How to Maximize Profits and Cut Costs. Simply put, it's radical. Which is exactly how Patagonia's founder, Yvon Chouinard, likes it. "This company is an experiment," says the 68-year-old Chouinard, leaning back on a redwood chair in his office. Though he's given to provocative statements - "I don't think we're going to be here 100 years from now as a society, or maybe even as a species" - anyone expecting a pugnacious character would be surprised. He speaks softly, with a California drawl. Athletically built and small-statured, forged by a life spent in nature's wildest corners, he looks more like a river guide than an executive. And again, this is no accident. To Chouinard, the average suit ranks somewhere between alcoholic and criminal on the respect scale, and American business, when powered by the endless consumption and discarding of stuff, is unimaginative at best and evil at worst, responsible for clear-cutting forests, polluting oceans, and bulldozing wetlands to make way for the next condo development. Its modus operandi is unsustainable growth, which he compares to an "out-of-control tumor." "I would never be happy playing by the normal rules of business," he writes in his book "Let My People Go Surfing," a combination memoir and green-business primer. "I wanted to distance myself as far as possible from those pasty-faced corpses in suits I saw in airline magazine ads ... I wanted to be a fur trapper when I grew up." Except he didn't end up skinning muskrats. Instead, he heads a company that made $270 million in revenues last year. No, that's not a huge number. Most of the company's competitors - Nike (Charts, Fortune 500), Adidas, and Timberland, to name a few - are much bigger. But from day one, Patagonia has punched above its weight - helped create a whole outdoor lifestyle, in fact. And decades before recycling became common practice, Patagonia was reusing materials. It was one of the first companies in America to provide onsite day care, both maternity and paternity leave and flextime. It used its lushly designed mail-order catalog to speak out about issues like genetically modified food and overfishing, proving that a company can benefit from having a voice and a moral compass, and that a clothing-company owner who quotes Thoreau ("Beware of any enterprises that require a new set of clothes") isn't necessarily a paradox. Along the way, Patagonia's conscience has rubbed off on others, from smaller enterprises like Clif Bar to larger ones like Levi Strauss and the Gap (Charts, Fortune 500). Even Wal-Mart (Charts, Fortune 500): "The one thing that impresses me is the power of the people who work at Patagonia," says Matt Kistler, a senior vice president at Sam's Club, the warehouse-store division of Wal-Mart. "I was very impressed to see how involved in sustainability their employees are. They're tremendously knowledgeable and want to do the right thing." So how did this antibusinessman's experimental little company become so influential? How did Chouinard hack his own contrarian path to success by putting the Earth first, questioning growth, ignoring fashion, making goods that don't break or wear out, telling customers to buy less, discontinuing his own profitable products, giving away chunks of earnings and saying things like, "If you're not pissing off 50 percent of the people, you're not trying hard enough"? And given Chouinard's intention to prove that "business can make a profit without losing its soul," how did he get so cozy with Wal-Mart? To answer these questions you have to go back to 1957, to a garage in Burbank, Calif. |

Sponsors

| ||||||||||||||||||||