This old guy sure can pick 'emFortune's Oliver Ryan looks at how legendary media investor Alan Patricof has found new life in the Big Apple's web startup scene.(Fortune Magazine) -- "I kept hearing, 'We won't invest less than five to ten million, and we have to take at least 20% of the company,'" says New York venture capitalist Alan Patricof. We're sitting in his office on the 53rd floor of the Citigroup Center in Manhattan, and the man who founded the $20 billion private equity colossus Apax Partners is talking about how so many VCs are too bloated to invest in web-media startups. "I heard them say 'It doesn't move the needle' enough times to think, If everyone is saying that, there's got to be a hole in the market!"

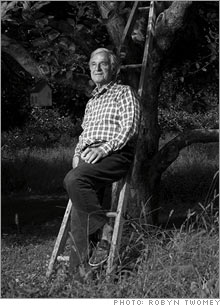

Framed by the glittering Chrysler Building, which fills the windows behind him, the 72-year-old Patricof hardly cuts the figure of your typical web guy. His face is craggy, his hair a disheveled mop of salt and pepper, and the combined effect of his oversized glasses and loose-fitting suit is distinctly pre-Internet. A breadbox-sized Dictaphone sits on one side of his desk. Yes, a Dictaphone. But there are also rows of neatly stacked business plans on that desk, from startups soliciting investments from his new VC firm, Greycroft Partners - proof that, his wardrobe notwithstanding, Patricof is back in vogue. "We're seeing 30 to 50 deals a week," he says. "New York has never been hotter." What's providing the heat is online advertising. The market for web ads jumped 35% in 2006 to almost $17 billion and has increased for ten consecutive quarters. The past two years saw a total of $7.3 billion in new spending, an ocean of cash that has given rise to a flood of web-media firms. Rich in dollars but poor in media connections, many tech-oriented VCs, Patricof insists, have trouble fostering such businesses. Today's web-media companies generally require less capital than traditional tech startups, but they need a bigger Rolodex to broker distribution partnerships and acquisitions. Enter Patricof, who is nothing if not well connected and loves placing small bets to big effect. "My philosophy, in a nutshell, is to wipe out the greatest amount of risk," he says, "with the least amount of money." Patricof may not have a Facebook profile, and he readily admits he's not the most tech-savvy guy in the room. But he has cherry-picked three partners from the worlds of media, tech, and venture capital - Dana Settle from VSP Capital; Drew Lipsher, former head of M&A at IGA Records; and Ian Sigalow, once of Boston Millennia Partners - and together they've snapped up stakes in 15 startups over the past year or so. The portfolio consists of exotic-sounding companies like Doppelganger, K2 Network, and Azureus, which make avatar-based instant-messaging environments, massively multiplayer online games, and peer-to-peer video-sharing networks, respectively. The firm bought into a social network for female entrepreneurs (Ladies Who Launch) and one for high school athletes (Takkle). And just as Patricof once owned pieces of It magazines like New York and Details, he's now backing the It blogs, like paidContent.org and the Huffington Post. It's too soon to declare Greycroft's first fund a winner, but the early returns are promising. The firm scored its first big exit in June, selling music exchange Pump Audio to Getty Images (Charts) for $42 million, a tidy seven-times return in just more than a year. This is not, however, the story of an old man freeloading off the work of his young MBAs: Without Patricof as the glue, Pump might never have even taken venture money. "I realized he was going to save us a huge amount of time," says Pump CEO Steve Ellis. "It was about being in a different league." That league consists of big-media executives, who these days hold all the exit money. With no '90s-era gaping IPO window, succeeding with a web-content play now means being on a regular lunch rotation with all the right moguls, many of whom are within direct view of Patricof's window. And as for those who aren't, Patricof's Outlook contacts file is a collection of 4,500 names to make even the most hyperconnected social networker jealous. Need the numbers for Rupert Murdoch and Michael Eisner? He's got 'em. Want to get in touch with, say, Sandy Weill? Patricof knows how. He runs with the Clintons and even entertainers like Russell Simmons. ("Alan is like a godfather to me," says the hip-hop giant.) Most people think of Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers as a VC firm; we all know Donaldson Lufkin & Jenrette as a storied investment bank. To Patricof, they are drinking buddies. "I call it the Alan factor," says Scott Hamilton of VoodooVox, a Patricof-backed company that puts advertising into telephone hold messages. "Anyone I want, Alan can get me to." But Patricof's success is about more than connections. Early-stage media companies are messy. Investing in this arena requires both a desire to be in the zeitgeist and an ability to haggle, prod, and nag. It's his mastery of this combination that prompts people like former Nickelodeon boss Albie Hecht to call Patricof "Gandalf the Wise." "No one approaches a new company with greater enthusiasm and wonder than Alan," says longtime partner Bob Machinist. "And nobody is more tenacious. When everyone else is sure a company is dead, Alan will still be at the graveyard praying at the stone. And he'll pray the body out of the ground." Not that Patricof's bedside manner - fearsome Jewish mother - is universally loved. He can be badgering and gruff. "He's the sort who gets in a cab and issues 30 corrective directions," says Ed Goodman, a veteran of the New York venture scene who got his start with Patricof. "Type A all the time." Patricof was born in 1934, the Depression-era son of working-class Russian immigrants who settled on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. His father, who became a small-time stockbroker after World War II, forbade Alan to go into brokering. If you have to go into finance, Dad advised, get into investment counseling. Patricof worked his way up in the business, eventually landing a job managing the Gottesman pulp and paper fortune, and gravitating toward the tiny private companies in the portfolio that had generally been overlooked. His love affair with media began in 1967 with an investment in the nascent New York magazine. It was a heady moment: The smart, gossipy magazine fast became the bible of the city's young and cultured, and Patricof, a bachelor between marriages, thrived as the founding chairman of the board. He even opened a nightclub in the Hamptons, which he claims with characteristic bravado was the first disco to mix a light show with music. "That's how I got to know a lot of people," he says. In 1969, Patricof raised $2.5 million and hung out his shingle as Alan Patricof Associates, becoming one of the country's first independent venture men. He poured money into magazines like Scientific American and small publishers like E.P. Dutton, and oversaw the acquisition by New York of the Village Voice, a move that set the stage for his first taste of serious boardroom strife. Having tasted expansion, New York's legendary founding editor, Clay Felker, set out to conquer California with New York clone New West. Unlike Patricof, however, Felker was notoriously profligate, and his new magazine was losing money. The saga played out in the tabloids, but in the end cooler heads sided with Patricof. The board sold a controlling share to Rupert Murdoch, prompting Felker to quit. "It was sad," recalls Patricof. "He was one of the most talented editors of his generation." With that drama behind him, Patricof thrived in the '80s, elbowing his way into 20-times returns with investments in Apple (Charts, Fortune 500) and AOL (Charts, Fortune 500), not to mention smaller successes like Details. His biggest hit, however, started as a side deal in Europe. Early on, Patricof dreamed of taking the American VC model overseas, and in the mid-1970s he hooked up with Ronald Cohen and Maurice Tch�nio, a Brit and a Frenchman who nurtured a similar ambition. The three set out to look for the "Intels of Europe" under the Patricof & Co. brand. By 1989, however, Cohen and Tch�nio had begun scouting out the bigger leveraged-buyout deals that were booming in New York, and they renamed themselves Apax Partners. Led by the runaway success of the European funds, Patricof's U.S. operations followed suit, eventually adopting both the investment strategy and the new name, and establishing Apax as a global giant of private equity along the lines of KKR or Blackstone (Charts). Dickering over expense accounts with hungry entrepreneurs had given way to buttoned-down billion-dollar road shows. "If you wanted to be successful, you wouldn't do a million-dollar investment," Patricof recalls. "Today's young Apax partners wouldn't even know what a venture deal was." Patricof saw his personal fortune balloon to several hundred million dollars and threw himself into politics and philanthropy. He was a key fundraiser for then-governor Bill Clinton in 1992 and is now the main moneyman for Senator Hillary Clinton's presidential campaign. He logged time for the World Bank and the UN and joined the boards of a series of nonprofits. This summer the Senate nominated him to the board of the Millennium Challenge Corp., a major Bush initiative chaired by Condoleezza Rice and Hank Paulson and intended to pour billions into global development. Patricof never gave up on early-stage investing, but come the go-go '90s, he found himself out of step. He was uncomfortable with the wildly inflated valuations, and even the richest VC deals had become a rounding error on his firm's bottom line. To add to his malaise, writer Michael Wolff, whose failed startup had gotten support from Patricof & Co.'s small investment-banking division, lampooned him as an antiquated, flighty Scrooge in the bestseller Burn Rate. In 2004, as Apax set out to raise capital for its latest $4.3 billion European fund, the partners killed what remained of their early-stage business. Not long after, Patricof announced he would leave the firm to start Greycroft, which would raise only $75 million and limit itself to investments of $3 million or less. Gossips whispered that he'd been pushed out, but Patricof remains in his old office and by all appearances is on good terms with his former partners. Eight of them bought into the new fund, along with 100 or so of Patricof's A-list pals, such as Eisner and Frank Biondi. Patricof claims he had little difficulty walking away. "It's a different kind of business now," he says of Apax. "These are spreadsheet people." His old partner Cohen understood perfectly: "He's gone back to his great love." The cavernous grand ballroom in New York's midtown Hilton is packed with nearly 600 new-media hustlers. It's the paidContent.org summer cocktail mixer, and various entrepreneurs and venture types urgently chat each other up, taking turns with media stars like MarketWatch founder Larry Kramer; his successor at CBS (Charts, Fortune 500), Quincy Smith; and Eric Nicoli, CEO of EMI. Patricof helped stock the room, and he's working the crowd like a candidate. He greets Kenneth Seiff, founder of DietTV.com. "Alan gave me my first job," says Seiff, as Patricof throws his arm around Sita Vasan, a senior investor in Intel's venture group. When paidContent founder Rafat Ali takes the stage, Patricof hovers like a vigilant tennis parent at a juniors' tournament. "I made the perfect investment first," Patricof says giddily. "If I'm going to be in digital media, what's better to own than the flagship of digital media?" It's a Goldilocks moment for Greycroft - Patricof has once again found the center of the investment industry. If the man has anything to complain about these days, it's that there's too much supply and too little time. He finds himself pressured to invest very early in a company's life cycle. "You're forced to spend before there are revenues," he says, which is anathema to a guy who built his reputation on extreme due diligence. Not that he's getting soft in his old age. He refused, for example, to pay up for a piece of his pal Russell Simmons's new startup, Global Grind. "People were fighting to lead the deal," recalls Simmons. "I said, 'Alan, your term sheet looks a little tight right now.' " "I don't think you can be in the early-stage business and be too careful," says Patricof, who has put only $4 million of his nine-figure net worth into Greycroft. That attitude has probably cost him some upside over the years, but it's also minimized the bleeding: He claims to have never lost money on a publishing deal. If he's conservative with his investments, he certainly is not with his time and energy. Surely a 70-something this rich doesn't have to show up at 6:30 every morning and haggle with entrepreneurs. But he does. "I work harder than anyone here," Patricof declares while pounding his desk one day at Greycroft. "He's insatiably curious," says Hillary Clinton. "He wants to know everything. And he is just absolutely one of the most energetic people I have known." Back at the paidContent mixer, a circle has formed around Patricof when he spots Joe Varet, a friend of his youngest son, Jamie, an up-and-coming indie filmmaker. Varet is CEO of web-video site LX.TV. "He and Jamie are a great team but total opposites," Patricof gushes before launching into a story about his son's passion for the Knicks. "Jamie's tickets were always way up in the cheap seats. But the minute the game started, he would start working his way down. By the end of the game, he was always sitting courtside!" Someone calls out that the apple hasn't fallen far from the tree. Patricof chuckles, pleased in a moment of self-reflection. "Yeah," he says. "I guess he gets it from me." |

Sponsors

|