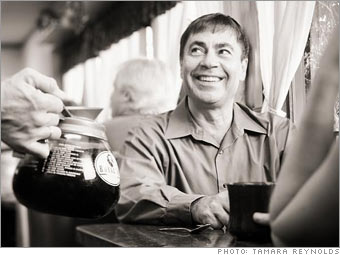

John Niggeling, 56, deletes e-mails from African dictators offering him a share of their fortunes. He ignores print ads promising thousands of dollars a week working from home. But three years ago, John Niggeling's nephew David told him about Learn Waterhouse, a company that promised investors a 10% monthly return, supposedly earned by trading debt from an elite group of "prime" banks overseas.

To Niggeling the returns sounded too good to be true. But for every question he had - how did Learn Waterhouse make money? Was it legal? Who else was investing? - his nephew had an answer. David kept after him.

"When he told me that a prominent local attorney was involved, I was hooked," says Niggeling.

In the summer of 2004, he took $25,000 out of his IRA and put it into Learn Waterhouse. Within weeks he received a check for $2,200. Encouraged, he invested another $83,000. A month later the Securities and Exchange Commission froze Learn Waterhouse's assets and alleged that its promoters had defrauded 1,700 investors out of $24.5 million. The investigation is ongoing.

According to SEC claims, the Learn Waterhouse deal was structured as a Ponzi scheme. In scams of this ilk, early investors appear to reap promised returns; in reality they're only getting money put in by later investors, but those early results make the scam look like a genuine bonanza.

But what really sold Niggeling was the hard sell by his nephew. With affinity fraud, as regulators call it, the con artist infiltrates a social group like a church or professional club, then persuades his new friends to enroll in his scheme.

According to research done by Emory University neuroscientist Gregory Berns, when we go along with peers, activity in a part of the brain that thinks analytically may decrease, presumably reducing our skepticism. And when we go against consensus, there's a reaction in the part of the brain usually triggered by fear. So we're afraid to go against the crowd, even when confronted with plain evidence.

HOW NOT TO BE A SUCKER The best antidote to any financial scam, of course, is to thoroughly check out the offer. That's easier said than done in an affinity fraud, however, when there's so much pressure to go along with the group.

As a result, it's important to establish your own personal due-diligence procedure now and resolve to follow your checklist to the letter when an "opportunity" appears, however much your friends swear it's legit. You rarely need to be a forensic accountant to find warning signs. In Niggeling's case, just typing "prime bank" into a search engine would have done it. The scam is so common that the SEC devotes an entire page on its website to it.

DON'T blindly follow family and friends

|

|