|

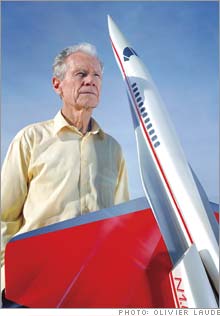

A supersonic business jet aims for takeoff Aerospace engineer Richard Tracy has clever technology and backing from a billionaire, says Business 2.0 Magazine. But can he succeed where many others have failed?

SAN FRANCISCO (Business 2.0 Magazine) - Imagine jetting from New York to Miami in an hour and a half, or flitting from New York to Tokyo in less than 10 hours - including a stop to refuel. That's the $1.4 billion dream of aerospace pioneer Richard Tracy, whose startup Aerion is hoping to build the first supersonic business jet, or SBJ.

With its Pinocchio-esque nose and slender fuselage, a model of the SBJ in Tracy's office bears some resemblance to the iconic Concorde. In truth, however, there are few similarities - the SBJ's stubby wings and side-mounted engines are strikingly different. And where the Concorde ferried as many as 100 passengers on a limited number of routes, Aerion's SBJ will carry no more than 12, is capable of landing almost anywhere, and will fly at Mach 1.5 - almost twice as fast as existing corporate jets. At least that's the idea. Tracy, who is now 75, has spent almost two decades refining the SBJ, and models of his designs have proven themselves in wind tunnels and computer simulations. But the aircraft is still several years from rolling down the runway - if, in truth, it ever does. Boosting a business jet With just five full-time employees, Aerion must now assemble an international consortium to provide the estimated $1.4 billion needed for further development. The SBJ must also survive rigorous regulatory reviews. Then there's the price tag: Aerion anticipates that the plane will cost $80 million - roughly 70 percent more than current high-end business jets like the Gulfstream G550. If all goes according to plan, the SBJ will enter service by 2011. But even as sales of inexpensive jets have taken off, the market for high-end private jets has also been healthy: Between 2003 and 2005, unit sales of business jets costing $40 million or more grew by 21 percent. In a study commissioned by Aerion, StrategyOne Consulting, an aviation-industry research firm in Wichita, Kan., estimated a market for about 250 SBJs over a 10-year period. And if Aerion succeeds, the SBJ will have little competition at its supersonic speeds. Tracy has found a solution to the problems of supersonic flight - chiefly high fuel consumption and operating costs - in an aerodynamic phenomenon called natural laminar flow. In simplified terms, natural laminar flow is a layer of smooth air generated by a precision-shaped wing as it rips through the atmosphere. On conventional wings, airflow becomes turbulent at supersonic speeds, creating greater aerodynamic resistance, or drag. The only way to overcome the drag is by increasing engine power, which explains why supersonic aircraft have a reputation for being both heavy and fuel-hungry. Natural laminar flow reduces those power requirements by significantly reducing drag. Applied to a supersonic business jet, the technology dazzles: The plane is so light that it can use the smaller, less crowded commuter airports preferred by harried business execs, as well as by companies that lease corporate jets. Tracy's dream has attracted funding from corporate financier Robert M. Bass, and he's hired experienced executives. Now he's hoping to assemble a team of investors, aerospace subcontractors, and manufacturing experts by the end of the year that can bring the SBJ to fruition. The challenge of the boom Even beyond the financial challenges, anyone hoping to commercialize supersonic flight faces a formidable speed bump: the sonic boom. In the United States, the Federal Aviation Administration forbids commercial jets to fly faster than the speed of sound over land. Period. The reason is simple: People on the ground refuse to suffer the thunderous cracks created when aircraft push through the sound barrier. Various companies have tried to solve this riddle, but so far to no avail. Working in partnership with Boeing, NASA even spent $1.5 billion between 1988 and 1999 as part of an effort to develop a 300-passenger airliner that could fly at Mach 2.4. But in the end, the inability to suppress the big plane's sonic boom helped drive the supersonic airliner to an early grave. Some other nations have similar concerns, but their regulations offer a crucial loophole: They merely forbid aircraft to create a sonic boom loud enough to disturb people on the ground. The distinction may seem trivial, but in practice it allows jets to fly faster at high altitudes because the speed of sound varies with the temperature of the surrounding air. Sound travels at 761 mph at sea level and at roughly 660 mph at 51,000 feet (the Aerion jet's projected cruising altitude). Under FAA rules, the SBJ could fly no faster than Mach 1 over U.S. territory - meaning that, even at 51,000 feet, the plane would have to remain below 660 mph. Over Europe, however, it could go well past 700 mph, because even though the aircraft would create a sonic boom at that altitude, the shock waves wouldn't be audible on the ground. Aerospace firms have intensified efforts to persuade U.S. regulators to reconsider the zero-tolerance policy on supersonic flight, and the FAA has commissioned research to determine how much noise the public might be willing to accept. But Carl Burleson, director of the FAA's Office of Environment and Energy, says the agency won't change the regulations until it has a plane to test. That means the industry has a serious chicken-and-egg problem: No one will fund a plane that may not be allowed to fly, and the regulations won't change until a plane is built. Tracy himself is philosophical about the challenge Aerion faces. "The entrepreneurial success level in aviation is very low," he says. "Only a few survive." He nods toward a rendering of his SBJ, then adds, "I think this one might." In an industry where failed visionaries litter the tarmac, that almost passes for giddy optimism. This is an excerpt from a story in the June issue of Business 2.0. To read the complete version, click here. |

Sponsors

|