How to solve the financial crisis

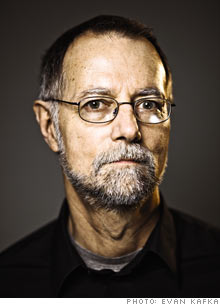

Cornell economist Robert H. Frank explains why a culture of excessive risk taking flourished - and what might push everyone from money managers to homebuyers to act more prudently.

|

| Robert Frank is a writer and economics professor at Cornell University. |

| MMA | 0.69% |

| $10K MMA | 0.42% |

| 6 month CD | 0.94% |

| 1 yr CD | 1.49% |

| 5 yr CD | 1.93% |

(Money Magazine) -- As a writer and an economics professor at Cornell University, Robert Frank has been trying for years to bridge the gap between the classroom and the real world. Though he has proved his command of the essentials of his profession - he wrote a textbook with Federal Reserve Board chief Ben Bernanke back in 2000 - his vision of economics is broader and more thought-provoking than most.

In "The Winner-Take-All Society" (1996) and "Luxury Fever" (2000), Frank analyzed the economic logic underlying sky-high salaries in business, sports, and entertainment, and the effects of luxury spending on middle-class Americans. In "The Economic Naturalist" (2007), he used economic principles to explain quirky questions of everyday life, like why drive-through ATMs have Braille buttons.

His new book, "The Economic Naturalist's Field Guide," collects dozens of his columns from the New York Times on topics ranging from gas taxes (he likes them) to the over-abundance of hedge fund managers. Contributing writer David Futrelle recently sought Frank's take on some of the hot-button economic issues of the day.

You have compared the problems that caused the financial mess to steroid use in pro sports. How so?

In both cases individual interests don't coincide with collective interests. If you are a fund manager, you want a lot of money under management because that's how you get paid. When some firm crafts a portfolio of slightly riskier securities and leverages it up 50 to 1 - that is, matches every investor dollar with $50 of borrowed money - investors are going to get a huge rate of return, assuming the underlying assets rise in price. Asset managers know investors want high returns, so a lot of them start offering that strategy.

Of course, each price drop produces huge losses for investors. But the managers know there's safety in numbers - if things go sour, they can say everybody else was doing the same thing.

It's like when one athlete gets a boost from steroids: Others have to adjust to the new level of performance.

Exactly. That logic extends to homeowners. During the presidential campaign, John McCain was hammering them for borrowing more than they could afford. But if you take into account the link between how much a house costs and the quality of schools in that neighborhood, you can see that if other people were borrowing more - which they were - and you didn't, then it would be your kids who ended up going to the schools where students score in the 20th percentile and have to go through metal detectors.

In sports the solution is to ban steroids and insist on testing. What's the solution in the financial world?

To start, you can regulate the amount of leverage asset managers could offer. But if you really want to blunt the incentive for investors to squeeze out ever higher returns, scrap the income tax and shift to a much more steeply progressive consumption tax. You would report people's income and savings to the IRS each year. The difference between those numbers is how much they consume.

Tax that instead of taxing people's income, and the government would strengthen the incentive to save and invest, and weaken the incentive to build bigger houses. If other people were building smaller houses, each investor would feel less compelled to take greater risks to keep up.

Wouldn't a consumption tax, which reduces consumer spending, be a drag on economic growth?

The tax should be phased in gradually after the economy recovers. The capital market would direct consumers' extra savings to investors, who would spend the money on capital goods. So total spending would remain the same - and it's total spending that determines output and employment.

You've said that executive pay in America is too high, but you also think pay caps are a bad idea. Why?

The jobs that are the most important, that create the most value, end up paying more. You need [salary] bidding wars to help identify the best people and steer them to the right places. What's not true is that they need big salaries to be willing to work hard. There's no evidence for that. If the differences in their post-tax pay were just a tiny fraction of what we see pretax, everything would work just about as well. So the simplest remedy would be to raise the tax on those high salaries.

But you argue that this logic doesn't apply as well to the financial industry, right?

In the case of, say, the software industry, there's a link between earnings and the extent to which good employees benefit the economy. In the finance industry there's no such link. Those companies earn more when they hire smarter people largely because smarter people can figure out more devious ways to unload risk onto other people.

Anytime it looks as if individuals are generating huge profits for a financial firm, I think the presumption should be that there's some market failure they're exploiting. Regulation can eliminate those failures and therefore those profits. Pay caps are a clumsy instrument. But if you had them in the financial industry, life would go on.

Lower consumer spending has made the downturn worse. Should we feel guilty that we're not spending enough?

No. The amount an individual spends is too small to make a difference. Only the government can print money and borrow it on a big enough scale. But if you want to spend, do it in a smart way - by adding insulation to your house, for example. That puts people to work without making your balance sheet worse in the long run.

"A lot of people are happy to blast the idea of a consumption tax without having heard the logic of it."

Want a Money Makeover? E-mail us at makeover@moneymail.com. ![]()