Health care reform: What small business wants

Insurance costs are killing small firms -- but many entrepreneurs are ideologically opposed to government-backed health coverage.

|

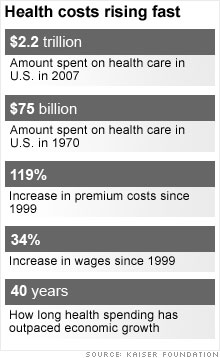

| Premiums for covering the seven employees at Jim Henderson's St. Louis construction-supply company have jumped almost 160% in the last decade. |

NEW YORK (CNNMoney.com) -- As Congress prepares to do battle over health reform, a parallel dispute is shaping up among small-business groups that are staking out opposing positions on a key element of reform proposals: whether Uncle Sam will take on a bigger role in offering insurance coverage or leave the field to the private market.

The so-called "public option," backed by President Obama and many Congressional Democrats, would set up a government-backed health insurance plan that would compete with private plans. Though details remain fuzzy, the proposal already has critics on both sides of the aisle decrying "government-run health care." The American Medical Association and private insurers oppose any public option.

Also resisting is the National Federation of Independent Businesses, the nation's largest and most influential small business group. A fierce critic of the Clinton administration's health care reform efforts a decade ago, the NFIB now considers universal health care to be one of its top legislative priorities. But it wants to see that care and coverage come from the private sector.

"Our members, who are entrepreneurs and risk takers, really do fundamentally at the end of the day want lower costs and competition, but they are going to be very skeptical of something that has a lot of government involvement," says Michelle Dimarob, the federation's legislative policy manager. The NFIB is instead pushing for a reform plan that would provide universal coverage and cut costs by increasing competition among private insurers, likely through the creation of government-mediated insurance pools.

Other small business advocates are more willing to let the government take the lead. The Main Street Alliance, founded last year to lobby on behalf of small-business owners around health reform, says its survey of 1,200 small business operators and self-employed entrepreneurs in the 12 states where it operates found that 59% prefer a public option, with only 26% wanting more private plan choices alone.

"Small business are in a position now where, frankly, they don't trust the insurance companies to be able to deliver quality, affordable health care," says alliance director Sam Blair. "Many business owners are saying we need a new kind of choice on the table."

Talk to small business owners themselves, and you'll hear a variety of opinions about how to fix health care. Most agree, however, on one thing: Increasing the variety of available insurance options is a must.

ReShonda Young, an Iowa Main Street Alliance member who runs a family-owned 34-employee courier service in Waterloo, Iowa, says she'll back anything that increases her choices. After two years of looking for coverage, she hasn't found anything affordable.

"I met with our broker in April. He gave me eight different quotes, and all of the quotes were from one company, which was Wellmark," Young says. Even if she covered only her 14 full-time staffers, the financial hit would increase her payroll costs by at least 12%.

St. Louis businessman Jim Henderson says that insurance premiums for his construction-supply company, Dynamic Sales, have jumped 159% in the last 11 years. "We do shop around, but being a small business with seven employees, [insurers] don't get too excited about that," says Henderson, an NFIB member.

"You're kind of locked in," agrees Daniel Eosco, who owns a 10-person Internet hosting service based in Bath, Maine.

For local small businesses like his, there's just two choices, he says: "You either go through Anthem [Blue Cross and Blue Shield], or you go through the state with Dirigo." Either way, you're tapping into the same back-end: Dirigo is a state-run program that provides subsidized coverage through a partnership with the private Anthem.

While Dirigo's premiums are lower, they're still high. "It was like $4,000 out of pocket to have a baby, and I was paying $1,100 a month for insurance," Eosco recalls. Covering each of his eight employees would cost at least $100,000 -- more than he can afford.

Eosco is a member of the Maine Small Business Coalition, a Main Street Alliance affiliate. He thinks a public insurance option would be a step in the right direction, but is nonetheless uneasy. "I make a good wage. Am I gonna get taxed higher so somebody who makes $20,000 a year has the same insurance as me? I'm all for public health care so more people can get health care, because it's the right thing to do. But I don't like the whole Robin Hood effect."

Most of all, though, he wonders: "Will it actually bring my health care costs down?"

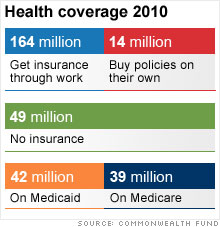

That's the key question, and one that industry analysts bitterly disagree on. Proponents point to report released in February by the philanthropic Commonwealth Fund, which projected that premiums for a public plan that reimbursed doctors based on Medicare pay rates would be "at least 20% below those currently available for a comparable benefit package in the private market."

What the public plan does is "create some leverage" to ensure that insurance companies don't find new ways to deny coverage, says Ellen Shaffer of the Center for Policy Analysis, which advocates a strong public health insurance plan. "Passing laws to regulate the insurance industry without some sort of alternative if they're not living up to it is really ineffective. You don't want a situation where you're trying to sue the insurance industry for 20 years to get them to obey the law."

The NFIB's Dimarob counters that using government clout to set rates would be unfair to private insurers ("'we're going to set all the rules and then we're going to compete against you' -- that doesn't seem like competition"), and it could also lead to cost-shifting, as doctors hike fees for the privately insured to make up for caps on public enrollees. A Families USA study, she notes, found that cost-shifting for care of the uninsured already inflates the costs for those with private insurance by an average of $368 per person.

With concerns like these in mind, some centrists are pinning their hopes on what's been dubbed the "level playing field" model, where a public insurer would be restricted from imposing Medicare-based fee structures. That would help soothe the fears of private insurers that they'd be undercut by a government competitor. "You need a credible threat in some markets where there is none now," says Len Nichols of the New America Foundation, who has advocated such a plan. "The public plan could do that, just by bidding fairly." Plus, he adds, "if you pay market rates, there's no cost-shifting, so you've solved that problem."

Small business owner Young is likewise hopeful that the mere existence of a public option could help lower costs.

"I personally worked for insurance companies for 12 years," she says. "I know that there could be some cost savings there. But without some kind of competition or regulation, I don't see what their incentive is to lower their costs." ![]()

-

The Cheesecake Factory created smaller portions to survive the downturn. Play

-

A breeder of award-winning marijuana seeds is following the money and heading to the U.S. More

-

Most small businesses die within five years, but Amish businesses have a survival rate north of 90%. More

-

The 10 most popular franchise brands over the past decade -- and their failure rates. More

-

These firms are the last left in America making iconic products now in their twilight. More