The Etsy Wars

Artisans flocked to this online marketplace, but few made enough to quit their day jobs. Now comes the struggle to keep them.

|

| Rob Kalin, founder of Etsy |

|

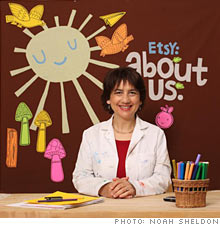

| CEO Maria Thomas, former head of digital media at NPR, took charge of Etsy last year. |

|

| Angelica Schaaf is one of six bloggers at Etsybitch. |

(Fortune Small Business) -- Some entrepreneurs sketch their business plans on napkins in cafs. Rob Kalin created his plan in masking tape on the floor of his walk-up apartment in Brooklyn.

It was 2005, and Kalin was a twentysomething Web site designer. He did woodwork in his spare time and was looking for an online marketplace to sell his wares. EBay (EBAY, Fortune 500) was an option, but it seemed soulless, like a garage sale full of unloved secondhand junk.

Kalin envisioned a site that would be entirely devoted to artisans selling their crafts -- and decided to build it. So he pulled out a roll of masking tape and started mapping the site on his carpet. "I wanted to change the world," says Kalin, now 29. "My goal was to empower people to make a living making things."

Four years later Kalin's online marketplace, Etsy, boasts 2.4 million registered members in 150 countries. Its more than 155,000 active vendors sold $58 million worth of goods in the first five months of 2009, doubling Etsy's sales volume over the same period last year. Despite the recession, the site facilitated sales of $87.5 million in 2008 and is expected to break even for the first time later this year.

Etsy has built an empire of entrepreneurs -- called Etsians -- whose products range from rag dolls to squirrel-foot earrings and beards made of yarn. But only a handful of sellers actually make a living on Etsy. And as a new CEO seeks to improve the site, some Etsians are complaining that they're being sold a bill of goods. Meanwhile, upstart competitors like ArtFire and DaWanda are happy to welcome disaffected Etsians.

Etsy's growth depends entirely on the participation of sellers. The 70-employee company, based in Brooklyn, takes a 3.5% cut of each sale and charges 20 cents every time an item is listed on the site. (Many Etsians pay to list the same things over and over.) There's also a showcase page where sellers pay between $7 and $15 to have their wares featured for 24 hours. Etsy does not disclose revenues, but Kalin says it takes in more than $12 million a year in fees. Investors have valued the firm at $100 million.

It's not hard to see why. Frustration with big-box stores and mass-produced goods has been bubbling up for years. Recession-era consumers are seeking unique, inexpensive gifts. More Americans seem interested in being "makers of things, not just consumers," to quote our new president. You can see the trend in events such as Maker Faire (see "Make Believers," February 2009) and the Renegade Craft Fair, both of which are held annually in multiple cities.

Seldom has a revolution felt so mild: Workers of the world, you knit!

Etsy actively markets itself as a venue where the arts-and-crafts set can achieve entrepreneurial success. Kalin often talks about creating an economy of diverse owners. Each week the official Etsy blog, called the Storque, runs a feature called Quit Your Day Job, profiling sellers who have stopped punching the corporate clock. Yet Etsy spokesman Adam Brown acknowledges that the "vast majority" of sellers use the site as a "secondary source of income."

Some Etsy sellers say the Quit Your Day Job campaign doesn't jibe with reality.

"My time works out to less than minimum wage, and not a dependable wage at that," says Susan Morgan Hoth, a 60-year-old retired teacher in Richmond who sells hand-painted silk scarves on the site. Hoth bought a new sofa and went traveling on the proceeds from her sales. But other sellers "think they're supporting themselves when their boyfriends pay the rent," Hoth says. "A lot of young girls on Etsy are headed for a shock when they get older and don't have anything." (Ninety-six percent of Etsy sellers are women.)

Etsy has spawned a few self-sustaining entrepreneurs. The busiest vendors on the site sell craft supplies to other Etsians; the site's top three sellers of handmade products all claim six-figure annual revenues. Leading seller Emily Martin, who sells her prints and paintings through an Etsy store called the Black Apple, appeared on The Martha Stewart Show in March. Martin was shocked when Stewart announced that her guest ran "a six-figure business." Only Etsy knew her gross revenue; Martin had never wanted it made public.

"Etsy was selling the idea of being able to quit your day job really hard," she says. An Etsy spokesman admits that the site used to boast -- without naming names -- that its top sellers made six figures.

Still, some vendors are downright angry that Etsy markets itself as a platform for small businesses.

"It's a very appealing thing to say if you're trying to attract sellers, investors or a buyer for your company," says Angelica Schaaf, 29, a stay-at-home mom in Rio Rancho, N.M. In 2005, Schaaf launched what she describes as a "semi-successful" Etsy store, Desert Maiden Bathworks. She borrowed startup capital from her father and hopes to pay him back in 10 years.

Since May 2008, Schaaf has been one of six women behind the blog Etsybitch. (The other five are anonymous.) Etsybitch claims to draw 10,000 visitors a month. The bloggers are peeved about Etsy's dictatorial habit of quashing debate on its own user forums. Etsy occasionally "mutes" contentious members, preventing them from posting.

In June, for example, some Etsians posted forum comments complaining that Etsy had taken days to remove a listing for a handmade replica of a 1930s Nazi flag. Less than 30 minutes later, a site moderator shut down the topic thread. The site's spokesman simply points out that Etsy forbids "discussing a specific member, store or item in a negative way."

Etsybitch has also taken the site to task for playing favorites among sellers and for its allegedly poor customer service.

"You join Etsy because you've been selling on eBay or at craft fairs and you're enamored with this alternative," says Schaaf. "There are people on Etsy who are really great. But it has major flaws. And a lot of people are so in love with Etsy, they can't think straight."

Of course, many Etsy sellers aren't looking to make a ton of money. "It's just such a cool, supportive outlet to do creative things," says Mike Guthrie, 26, of Tampa. Guthrie, his girlfriend and her father run SecondLineFrames, an Etsy store that sells picture frames made of salvaged wood from houses wrecked in Hurricane Katrina. A portion of the proceeds goes to help rebuild neighborhoods in New Orleans.

But as it grows, Etsy has suffered a minor exodus of sellers. Tony Ford, vice president of rival site ArtFire, says his membership grew from zero to more than 15,000 sellers in seven months -- many of whom, he believes, came from Etsy. Ford is deliberately adding site features that Etsy sellers have requested, including a better search engine and a more user-friendly interface. He is also positioning his 10-employee company, based in Tucson, as David to Etsy's Goliath.

"We bootstrapped this whole thing," says Ford.

That's quite a contrast with Etsy, which has raised more than $30 million in capital since 2006. The money storm started when Kalin e-mailed Catarina Fake, co-founder of the online photo service Flickr. The two had never met; Kalin just wanted advice about choosing items for the site's home page. Fake's response led to what would become a $615,000 round of angel funding.

"This was a clear case of finding a parade and getting in front of it," Fake says. "It would be a tragedy for Etsy to stay small."

In January 2008, Etsy secured another $27.5 million in venture funding from a group of investors, including Accel Partners in Palo Alto and Union Square Ventures in New York City. Those two firms now own more than 35% of Etsy.

That made some sellers uneasy -- especially because Jim Breyer, an Etsy investor and a board member of Accel Partners, also sits on the board of Wal-Mart. Wal-Mart (WMT, Fortune 500) has been a b�te noire for Etsy sellers, who offer products such as a "Wal-Mart Zombie" wallet and a T-shirt with the words SWEAT SHOP in the style of the Wal-Mart logo.

Breyer says he received around 60 e-mails from concerned Etsians immediately after the announcement. "It is possible to be the lead independent director of Wal-Mart and be absolutely passionate about art and crafted goods," he says. "Over time Etsy sellers, as well as Etsy shareholders, can do very well if we stay true to our mission."

New money has meant new management. In April 2008, three months after Etsy closed its $27.5 million investment round, the company hired a new COO. Maria Thomas, 45, came from National Public Radio, where she'd been head of digital media. Within five months Thomas had replaced Kalin as CEO.

Thomas has a good sense of the Etsy spirit; she introduced herself on the Storque by uploading a video of herself playing an endearingly tin-eared solo on the drums -- a literally offbeat salute to creativity. "The social aspect of craft is huge," she says.

Earlier this year Kalin quietly took himself off the payroll. The site "was very incomplete and not up to my standards," he says. Kalin wanted to do something different, something lean and stripped-down. He remains chairman of Etsy's board, though his focus has shifted to his next startup, which he calls Parachutes.

The details are still vague, but Parachutes' goal resembles Etsy's: enabling artisans to collaborate and make a living from their crafts. This time, though, Kalin wants sellers to work in close proximity, business incubator-style, as well as online. He has already established his first craft collective (Parachute 101, based in Brooklyn's gritty Red Hook district) with some of his favorite Etsy sellers.

Call it the next stage in Etsian evolution: diversification.

"Sellers need to realize that making any significant profit is going to take venues other than the saturated market on Etsy," says Cynthia Gentry, an Etsy seller and professional sociologist based in Texas. "You might make it big on Etsy with a kick-ass product and lots of work. You might also win the lottery." ![]()

-

The Cheesecake Factory created smaller portions to survive the downturn. Play

-

A breeder of award-winning marijuana seeds is following the money and heading to the U.S. More

-

Most small businesses die within five years, but Amish businesses have a survival rate north of 90%. More

-

The 10 most popular franchise brands over the past decade -- and their failure rates. More

-

These firms are the last left in America making iconic products now in their twilight. More