Search News

FORTUNE -- It's a title to conjure with: chief information officer of the United States. Vivek Kundra, 36, is the first person ever to hold it, having been given the new job by President Obama in March 2009. And what a job -- the U.S. government is the world's largest consumer of information technology, spending about $80 billion on it each year. Much of that money is wasted. The federal government has accumulated 24,000 websites and more than 10,000 separate IT systems; servers in some agencies are idle 93% of the time. Kundra's assignment has been to improve efficiency while also making the government's staggering quantities of valuable data more available and useful to the public.

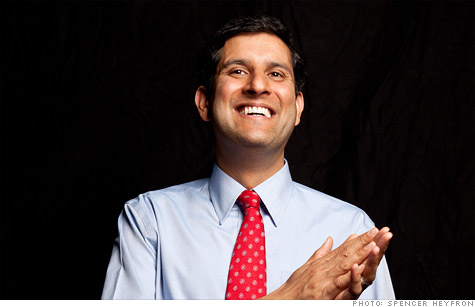

Kundra recently announced he's leaving Washington to accept a fellowship at Harvard. He departs to acclaim; the World Economic Forum this year named him one of its Young Global Leaders. Born in New Delhi, Kundra moved to the Washington, D.C., area with his family at age 11. After earning bachelor's and master's degrees from the University of Maryland, he worked at tech startups and was the District of Columbia's chief technology officer before Obama called. Kundra talked recently with Fortune's Geoff Colvin.

Q: As the first person to hold this job, what did you find when you showed up for work?

A: If the Obama campaign represented a sleek iPhone, the White House was much more like the rotary phone. We found that billions of dollars in information technology projects were years behind schedule and after the money was spent weren't even working. For example, at the Department of Defense there was an IT project where they had spent 12 years and $1 billion, and nothing worked. We ended up terminating that project. The President had to fight tooth and nail just to get a BlackBerry. For my staff, mobile devices were assigned based on the square footage of your office and how many years you were in government. I felt like I'd gone back decades.

What were the biggest opportunities?

They were in four areas. First, we wanted to look at this $80 billion that we're spending every year on IT -- how do we make sure that taxpayer dollars are not wasted on investments that don't produce dividends for the American people? Second was cracking down on inefficient infrastructure -- billions of dollars on data centers. Third, cybersecurity. We wanted to shift away from a paperwork reporting model to address a risk that was real, whether it's nation states that are actively coming after our systems, or organized crime. You can't confront that by writing reports. And fourth, the most important opportunity was to tap into the ingenuity of the American people. For too long, Washington was designed with a view that Washington has a monopoly on the best thinking, and the reality is, it doesn't. So we wanted to use technology to tap into the millions of Americans who want to create a more perfect union.

Was there anything the federal government was really good at?

The government had excelled historically and continues to excel at the basic research that has helped create massive opportunities across the country and the world. At DARPA, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, which is where the Internet was born, there's some cutting-edge information technology work happening. Some of the best minds in cybersecurity are within the National Security Agency.

You created a plan for transforming federal IT management and near the top was a "cloud first" policy. What does that mean? And why did you consider it important?

I asked a very simple question: How would a startup company launch in the private sector? If you went to venture capitalists or your board of directors and said, "I need millions of dollars to hire an army of consultants to stand up my e-mail system and build a custom financial system and build out a data center so I can host a website," you would get laughed out of the room. And that's exactly what the federal government was doing.

Startups are going to Google (GOOG, Fortune 500) for e-mail, or to Microsoft (MSFT, Fortune 500), or to Hotmail. They're going to Intuit (INTU) and using QuickBooks for the financial systems. They're going to a number of providers online to stand up a website, and they get value day one, literally. They don't spend months or years procuring those services. Imagine if the federal government, with purchasing power of $80 billion, demanded from the vendor community, "We want value day one. We don't want to wait years, and we don't want to spend millions of dollars, because we've seen this movie, and it always ends poorly." That is one of the reasons I focused on cloud first.

I also looked at the wasteful spending on infrastructure -- from 432 data centers in 1998 to over 2,000 today. Average utilization of processing power is under 27%. Average utilization of storage is under 40%.

So you've announced a plan for closing or consolidating hundreds of those data centers. Makes sense, but why wasn't it done long before you got there?

In Washington there's a huge focus on policy, not a lot of focus on execution. So one of the things we did from day one is set specific timelines. We put in people who were responsible for executing and were ruthless about making sure we're delivering.

For example, one of the first things I did was take the picture of every CIO in the federal government. We set up an IT dashboard online, and I put their pictures right next to the IT projects they were responsible for. You could see on this IT dashboard whether that project was on schedule or not. The President actually looked at the IT dashboard, so we took a picture of that and put it online. Moments later, I started getting many phone calls from CIOs who said, "For the first time, my cabinet secretary is asking me why this project is red or green or yellow." One agency ended up halting 45 IT projects immediately. It was just the act of shining light and making sure you focus on execution, not only policy.

The IT dashboard was one of your high-profile initiatives. Does it now show the progress of all major federal IT projects?

Absolutely. You can see every major IT project and how we're doing. Besides the picture of the person who's responsible, I also decided to put up every company that had won those contracts. So all of a sudden, CEOs were coming to see me. A number of CEOs issued press releases around how all their projects are green. It created this incentive to perform.

Shining light alone is not sufficient, so I decided to go after projects that are not performing well. We were able to save $3 billion after terminating projects that were not working, or de-scoping them. We also halted $20 billion worth of financial systems last summer because these were projects we had spent billions on with very little to show to taxpayers.

All those agency CIOs report to you, but you're not really their boss. As a practical matter, how can you make things happen?

The key is, you've got to keep following up. It's a very simple management principle. You can't just shine light and hope that results will follow. You've got to be relentless about going after some of these IT projects.

I realized when I was going after these projects, terminating them or de-scoping them, that I wasn't the most popular person in the room. But I didn't take the job to be the most popular person in the room. Vendors were very upset because we terminated multimillion-dollar IT contracts. CIOs may have spent years on a specific project, so they continued to throw good money after bad and were emotionally tied to those projects. But at some point, you need to just step back and ask the tough questions.

A fact of life in government is that administrators have little incentive to reduce their budgets. Frequently it's just the opposite. How do you fight that tendency?

One of the reform areas we're pushing very, very hard -- but it's going to require an act of Congress -- is to change the way we budget for information technology. The budget cycle takes up to two years. So these CIOs are thinking about where they're going to spend their money two years from today. Steve Jobs develops an iPhone in less time than it takes average agencies to get their budget done -- and that's just the budget, not the spending.

We're trying to reform the way we budget federal IT so that the incentives are much more aligned with delivering these projects on time. Everybody thinks they have one shot at getting the funding, so they try to boil the ocean instead of moving toward these lighter-weight, agile methodologies for how you deploy projects, and making sure that the money they save they can keep to reinvest.

That helps explain something you were recently quoted as saying: "The average schoolkid probably has better technology in his or her backpack than most of us do in government offices." How do you fix that while also trying to control IT spending?

There's a huge divide between the consumer space and the public sector. Why? The reason is that in government there isn't a Darwinian pressure to innovate that's in the consumer space. Consumer companies are one click away from extinction, so they have to innovate constantly. Yet in enterprise IT, which is far inferior to consumer IT, victory is considered winning that contract. Once companies win that contract, the incentives are to optimize their margins, not to innovate or make sure they're providing better services.

You address that problem by adopting consumer technologies. Why are we even in the business of giving mobile devices at an enterprise level? Let all government employees go out there, pick whatever mobile device they want, and let competition decide which is a better technology, instead of having some random bureaucrat setting a standard for millions of people.

One of your major efforts was Data.gov, which makes hundreds of thousands of government data sets available to the public in the hope that the private sector will create valuable ways to use all that data. Have the results been what you aimed for?

Absolutely. We launched it in May of 2009. It started with 47 data sets. Today there are over 390,000 data sets on Data.gov on every aspect of government operations from health care to education to what's happening across state and local governments. There are 19 countries that have replicated Data.gov. Over 29 states have replicated the Data.gov platform, and a dozen cities across the country, from New York City to San Francisco, have launched these platforms.

In my view this is going to be a transformational platform. We're now putting up money for competitions for developers and the average American to come in and create applications that the government couldn't even imagine. When we initially launched this, somebody developed an app called Flyontime.us that allows you to see average delays of flights and people tweeting wait times at airports, so you can make an intelligent decision. Since then, search engines like Bing have used data that's come out of Medicare and Medicaid that allows you to see how hospitals are rated by patients and outcomes from those hospitals. If you type the name of a hospital, right in your search results you can see that. An iPhone app allows an expectant mother, before she buys a crib, to scan that product and see whether it's been recalled. It's shifting power to third parties and recognizing that the government doesn't have to build everything. It can create a platform very much like what the U.S. military did with GPS satellites that gave birth to an entire GPS industry, or what the National Institutes of Health did with the Human Genome Project that gave birth to personalized medicine.

A lot of companies are saving significant money by using videoconferencing, document sharing, and other collaboration tools. Is the federal government making much progress on that?

Yes. An interesting case study is what the Social Security Administration is doing with videoconferencing. People don't have to drive down to a Social Security office -- they're doing it through videoconferencing. The General Services Administration recently moved to Google Apps, and part of what they're going to be doing is using the consumer tools to do video online instead of building these massive brick-and-mortar platforms.

All of which would be uncontroversial in any private enterprise, but it's a big change at the federal level.

It's a huge change, and part of the reason is that we're introducing new competition. Companies like Amazon (AMZN, Fortune 500), Salesforce.com (CRM), and Google, which had never competed for government business, are coming in and aggressively going after that $80 billion opportunity. That is great from a taxpayer perspective. We want more competition, not less. Historically with public sector IT, every solution was based on hourly rates of consultants. So you would throw bodies at problems rather than trying to find meaningful disruptive technical solutions.

Another IT tool, business analytics, helps companies spot improper payments, among other things. The Office of Management and Budget estimates the government lost $98 billion to improper payments in 2009, which sounds like a huge opportunity. Is it?

It is. On the Recovery Act [the stimulus bill], we worked with a company called Palantir, which is in business analytics. To prevent fraud, we were able to slice and dice and cube all this data to make sure that entities that were winning these contracts were appropriate. The ability to investigate and go through massive volumes of data allowed us to prevent it.

Now we're taking that practice and applying it to Medicare, Medicaid, and other grant programs. Over half a trillion dollars in grants go to state and local governments and then to private sector companies, and the fraud, coupled with the error rate, is huge. That is a huge opportunity. ![]()