Search News

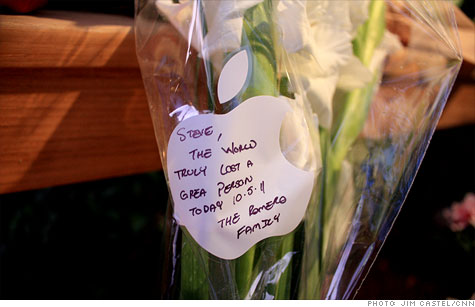

An apple-shaped note to Steve Jobs was left with flowers outside Apple's headquarters Thursday.

NEW YORK (CNNMoney) -- Steve Jobs is gone, leaving behind a void at the company he founded similar to the gaps left by other American visionaries like Walt Disney, Sam Walton, Henry Ford and Ray Kroc upon their passings.

That kind of genius is never replaced -- but companies that lost an iconic leader must decide how to move on.

The best course of action is not always apparent. The list of companies that lost their way following the exit of a visionary founder is a long one.

Walt Disney Productions, now known as The Walt Disney Co. (DIS, Fortune 500), actually left its founder's desk vacant for years following his 1966 death. The company stayed in the family, and the question, "What would Walt do?" permeated every strategic discussion. Afraid to do anything new, the Disney family unsuccessfully attempted to replicate Walt Disney's vision for two decades.

After Henry Ford died in 1947, the company's leadership also stayed within the family -- and its dominance in the automobile industry faded. General Motors (GM, Fortune 500) steadily stole market share. Ford (F, Fortune 500) had a resurgence in the 1970s, but it has never reclaimed its No. 1 ranking.

RCA leader David Sarnoff died in 1971, leaving behind a company that built a broadly successful electronics business atop its invention of the color television. But the company unwisely chose Sarnoff's son Robert to succeed him, and RCA failed in its expansion beyond the technology field. It was bought by General Electric (GE, Fortune 500) in 1986 and broken up for parts.

The list goes on.

Then there's the flip side: The companies that succeeded at carrying on after their visionaries were gone.

Wal-Mart (WMT, Fortune 500) founder Sam Walton died in 1992. The company's leadership expanded Wal-Mart tremendously in the years since, but has continued on the course he set. David Glass, who succeeded Walton as CEO in 1984 (Walton then became the company's chairman), was groomed under Walton for years and cultivated a deep bench that maintained the company's consistency.

After Intel (INTC, Fortune 500) founder Gordon Moore left the company in 1997, Craig Barrett and Paul Otellini -- both outsized personalities -- steered the company in new and successful directions.

McDonald's (MCD, Fortune 500) might be the greatest leadership succession story of all time. Founder Ray Kroc died in 1984, yet his genius invention of a chain focused on machine-like price control, marketing, uniformity and consistency made it easy to continue his vision. Tragedy hit McDonald's in 2004 and 2005, when two of its CEOs died within nine months of one another. Yet the company hardly missed a beat.

So what's the right model for Apple (AAPL, Fortune 500)? Staying the course was the wrong move for Disney, but it worked well for Wal-Mart and McDonald's. New vision kept Intel a success, but it destroyed RCA.

The biggest challenge for companies that lose their iconic leaders is to determine what their new identity will be. Can they can effectively carry on the former leader's vision, or is it best to evolve beyond it?

It's a complicated question with no clear answer. Unsurprisingly, experts differ about which course is best for Apple.

Some say Apple should stay the course. That's what Tim Cook suggested in his memo to employees on Aug. 25, a day after Steve Jobs resigned as CEO, when he wrote, "I want you to be confident that Apple is not going to change."

Jim Post, a professor at Boston University's School of Management, thinks that's a wise move. "Caretaker" CEOs can be essential in keeping a strong firm running smoothly.

"The general lesson learned is you don't replace a true visionary with another visionary in the next generation of management," he said.

Others think that carrying on Jobs' legacy will work for the immediate future, but that Apple will eventually need to think beyond the limits of what its founder would have done.

"In executive succession, you have to maintain what's working in the present but also have some selected apathy about what you'd done in the past," said Thomas Allen, professor at MIT's Sloan School of Management. "No one is going to be a second act for Jobs. Tim Cook wants to keep the spirit of Jobs alive but he has to know that may have to change eventually."

That's the catch: Radical upheaval is what made Apple great. Founders and iconoclasts have unique standing to take "bet the company" risks -- something Steve Jobs did repeatedly throughout his career. He's revered for getting so many of them right.

That will be the real test for Tim Cook. In the short term -- say, the next few years -- Apple is poised to keep its vanguard spot in the tech industry.

Though the company was secretive about its succession plans, insiders say Jobs groomed Cook and other top executives to smoothly take over both operationally and creatively. With or without Jobs, Apple's momentum is expected carry it to a lofty new high: It's on track to become the world's largest technology company, in terms of sales, by the end of next year. It is already the highest-valued technology company on the stock market, and its just-finished quarter is likely to be another record-breaking one.

But what happens five years out, 10 years out? What happens when the tech industry has its next tectonic shift?

Steve Jobs' ability to tear up something that appears to be succeeding and put in place something even better was uncanny. The Lisa was replaced with the Mac. The iPod Mini was scrapped in favor of the Nano. Apple has admitted that the iPad is eating into its Mac sales -- but it went ahead anyway and invented a whole new market despite the potential for cannibalization.

"Even Steve wouldn't continue Steve's vision," said Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, senior associate dean at Yale's School of Management. "Jobs had the ability to -- and did -- obliterate each model he created and cannibalize his own products. Temporarily, they have a team that can do a swell job, but they're missing that agitator." ![]()