Search News

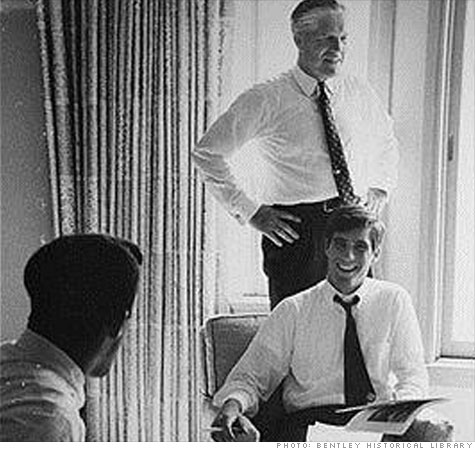

Candidate George Romney (standing) set a high bar when, in 1967, he released 12 year's worth of tax returns. His son Mitt (lower right) should follow suit, argues tax expert Joseph J. Thorndike.

Joseph J. Thorndike is a contributing editor at Tax Analysts and a columnist for Tax Notes magazine, where a longer version of this article first appeared. He is also director of the Tax History Project at Tax Analysts, which includes an archive of presidential tax returns. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely his own.

Mitt Romney does not seem eager to release his tax returns. Hounded by Republican rivals, he said this week that he'll do so in April.

Presumably, Romney is reluctant to be caught violating the so-called Buffett Rule, President Obama's aspirational standard for tax reform. The rule holds that no household making more than $1 million annually should pay a smaller share of its income in taxes than middle-income families pay.

The Buffett Rule may be vague and unenforceable, but it's good politics, so it makes sense for Romney to release his returns. All he has to do is look at what his father did as a candidate.

In 1967, Michigan Gov. George Romney set the bar high for tax disclosure by presidential candidates. While running for the Republican nomination, he was "badgered" by a writer for Look magazine to release his most recent tax return.

Romney refused. Releasing a single return wouldn't prove anything, he told the magazine's senior editor, T. George Harris. It could be a fluke, or even a cynical manipulation designed to make the candidate look good. What really mattered was how a candidate managed his personal finances over the long haul.

"Stumped by his argument," Harris wrote in the magazine, "I was not prepared for the move that it eventually led him to make: He ordered up all the Form 1040's that he and Mrs. Romney had filed over the past 12 years -- including those profitable ones when he saved the American Motors Corp. from bankruptcy and became a millionaire on the company's stock options."

Romney's disclosure was apparently unprecedented. While other candidates had released statements outlining their income, assets and other financial data, none had ever released his actual returns.

Romney's tax returns told an interesting story. To no one's surprise, they revealed him to be a rich man (although not nearly as rich as his son is reputed to be). His adjusted gross income ranged from a high of $566,771.47 in 1963 (roughly $4 million in current dollars) to a low of $78,483.85 in 1966 (about $527,000).

In some years, Romney's salary at AMC provided most of his income, but starting in 1960, he began to report considerable investment income. (His salary ranged from a high of $200,000 in 1959, when he was still an auto executive, to a low of $27,499 in 1963, when he was governor of Michigan.) His investment income followed the opposite trajectory, starting at a low of $3,541 in 1955 but rising to more than $500,000 by 1963.

Romney's income was impressive, but so were his deductions. In particular, his charitable contributions made headlines -- of the useful, not the embarrassing, variety. Over the 12-year period covered by the returns, George and Lenore Romney gave away 23% of their income to charity, including 19% to the Mormon church.

"One year, in 1960, they carefully gave away all but $389.59 of [George's] salary and bonus, $173,125," the magazine noted with apparent awe. Of course, the Romney's still collected $487,202.68 in dividends, interest and capital gains that year, so they weren't in much danger of starving. But still, the gifts were impressive. (Read: Millionaires ask Congress to raise their taxes)

Romney paid a lot of tax during the 12 years in question, although his average tax rate varied dramatically from year to year. It hit a high of 45.8% in 1961 and a low of 16.5% in 1966. Over the total period, however, it averaged 37%.

What might Mitt Romney learn from his father's experience with tax disclosure?

Romney Jr. should take a lesson from Romney Sr. and take the risk of public disclosure. He should challenge the Buffett Rule head-on, offering up his own Romney rule in honor of his father: "No presidential candidate should be afraid to confront the electorate with the truth, no matter how uncomfortable it might be for either of them."

In vague terms, Mitt Romney has already flirted with that approach. When pressed by reporters about his use of loopholes, Romney said: "I can tell you we follow the tax laws, and if there's an opportunity to save taxes, we, like anybody else in this country, will follow that opportunity."

That's entirely reasonable. And he should go even further.

Who wouldn't welcome excessive candor from a presidential candidate on this issue? It would place the blame for Romney's (presumably) low tax rate where it belongs: on Congress and the IRS. It would end all the distracting chatter about what Romney might or might not be hiding. And most important, it would make him seem like a stand-up guy.

Of course, it would take a certain amount of guts, too. But isn't that something we want in our president? ![]()

| Overnight Avg Rate | Latest | Change | Last Week |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 yr fixed | 3.80% | 3.88% | |

| 15 yr fixed | 3.20% | 3.23% | |

| 5/1 ARM | 3.84% | 3.88% | |

| 30 yr refi | 3.82% | 3.93% | |

| 15 yr refi | 3.20% | 3.23% |

Today's featured rates:

| Latest Report | Next Update |

|---|---|

| Home prices | Aug 28 |

| Consumer confidence | Aug 28 |

| GDP | Aug 29 |

| Manufacturing (ISM) | Sept 4 |

| Jobs | Sept 7 |

| Inflation (CPI) | Sept 14 |

| Retail sales | Sept 14 |