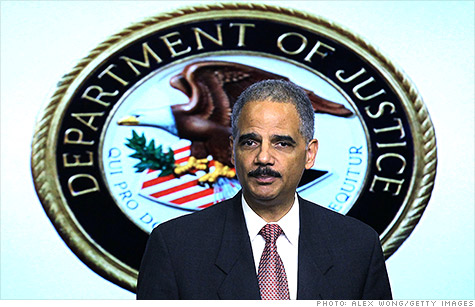

U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder.

NEW YORK (CNNMoney) -- If prosecutors want to go after Wall Street for its role in the financial crisis, they better watch the clock: The statute of limitations for many federal offenses is just about up.

For securities fraud and most other federal offenses, prosecutions must begin within five years, and the subprime lending bubble hit its peak in 2007.

"The statute is already becoming a concern in a broad range of cases," said Bill Black, a law professor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

Federal officials, however, have a number of ways around this problem.

For starters, they could pursue "tolling agreements" with the firms or individuals under investigation. In these agreements, the subjects of investigation agree to have the statute of limitations extended, and can earn more lenient treatment in return.

"Most people, faced with a choice of letting the statute of limitations roll on or getting indicted tomorrow, they'll choose the tolling agreement," said John Coffee, a professor at Columbia Law School.

One challenge with this approach is that if investigation targets don't believe the threat of imminent indictment is realistic, they may not agree to stretch the statute of limitations, Black said.

Another possibility is to pursue charges with a longer statute of limitations, said Michael Clark, a defense attorney with the law firm Duane Morris and a former federal prosecutor.

In mail and wire fraud cases that affect a financial institution, for example, the window extends to 10 years.

"If you can use one of the longer limitations periods to make it fit, and it's a federal case, that would be the cleanest way to do it," Clark said. "When you're talking about mortgage-backed securities that are being marketed and picked up by financial institutions, I think it's worth a look."

State officials too, could use their own laws to bring cases. In announcing a new task force earlier this year to investigate the mortgage meltdown, federal officials said they planned to pool resources with state attorneys general.

For now at least, Goldman Sachs (GS, Fortune 500) appears to be getting a pass. The Justice Department announced Thursday that it would not bring criminal charges against Goldman for its marketing of mortgage investments outlined in a Congressional report.

That decision has left some observers questioning whether other major cases will be brought.

"We don't know the facts, but it doesn't look good," Clark said. "What can they do to differentiate the next one that might be in the crosshairs?"

Officials at the Justice Department and the SEC did not respond to requests for comment. In its announcement this past week, the Justice Department left open the possibility of a Goldman case "if any additional or new evidence emerges."

Black said that while the Justice Department likely hopes to announce a headline-grabbing financial case before the presidential election in November, it will be easier to do so in connection with the Libor interest-rate rigging scandal.

"I think that's going to be their way to say they've done something," he said.