Search News

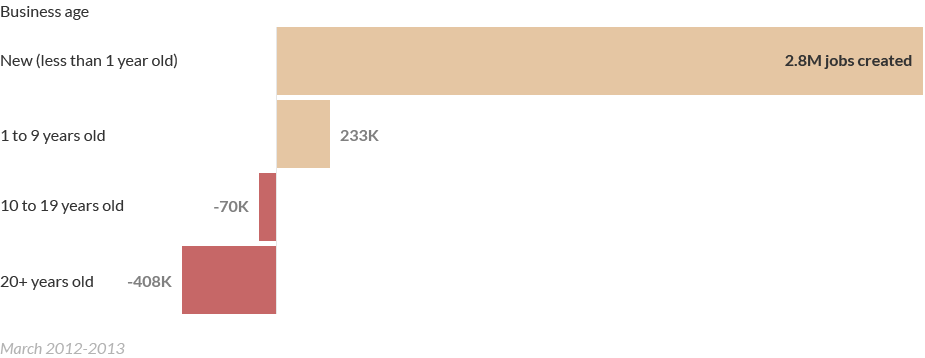

New businesses have long accounted for most of the jobs created in the U.S. economy.

Going back to 1993, when the Bureau of Labor Statistics started tracking the data, firms less than a year old have always been net job creators, whereas older firms have largely been job killers.

Take last year for example: New businesses added 2.8 million jobs from March 2012 to March 2013. Over that same time period, older firms cut 245,000 jobs. Young firms aren’t just tech startups. These establishments include corner bakeries, doctor's offices, plumbers, as well as high-tech firms.

Retail, leisure and hospitality are the single largest sectors for new businesses, accounting for about a third of all jobs added by new firms.

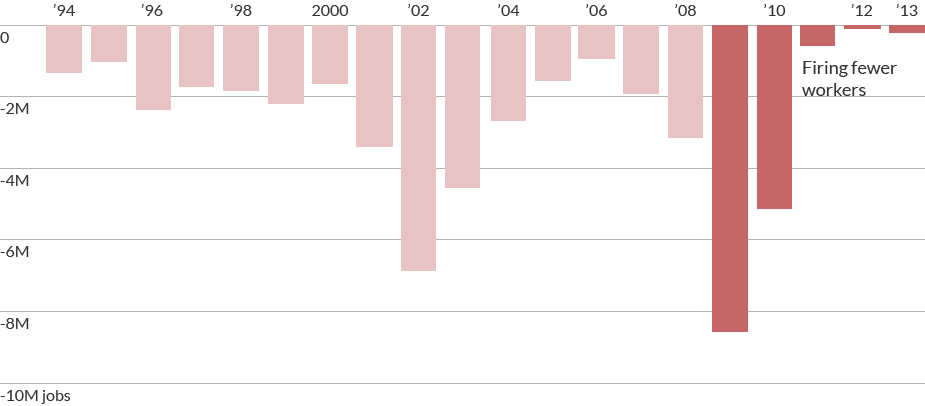

The good news is, older establishments are not cutting as many jobs as they used to. In the following chart, notice the deep job losses among firms one year and older in 2009 and 2010. Layoffs have dwindled since then, which is good news for workers at older companies.

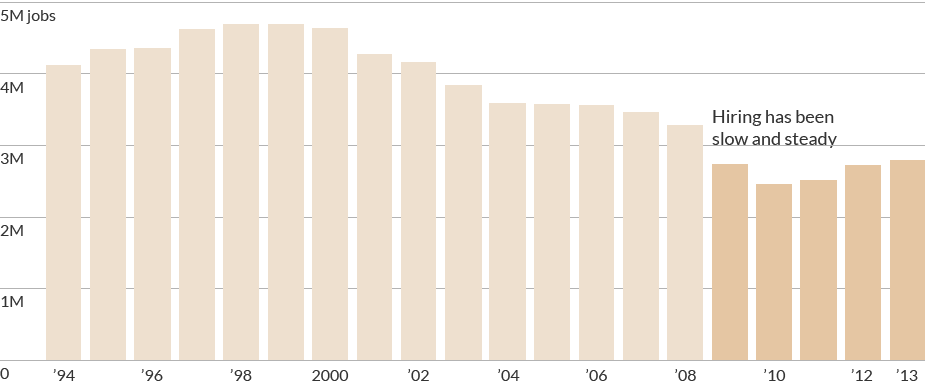

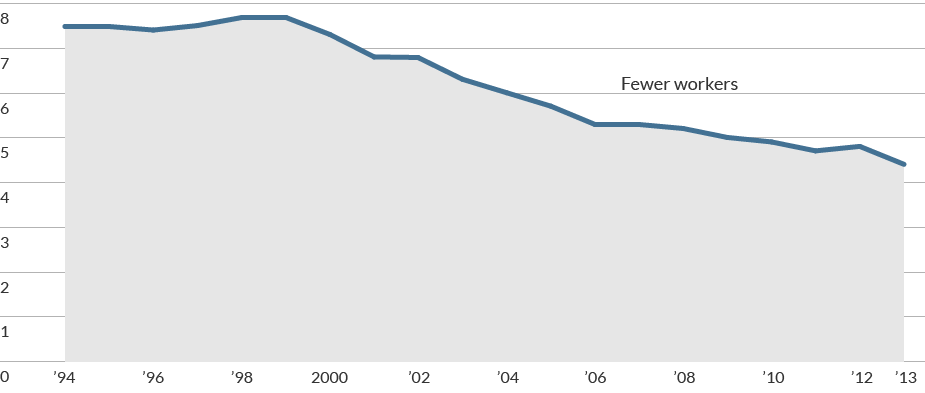

The bad news is, hiring by new businesses has been slowing in recent years, and it's unclear why. This hiring slowdown doesn't seem related to the recent recession — in fact, it started in 1999. "Start-ups still account for an outsized portion of job creation, but their importance is in decline over time," said Javier Miranda, principal economist for the U.S. Census Bureau's Center for Economic Studies.

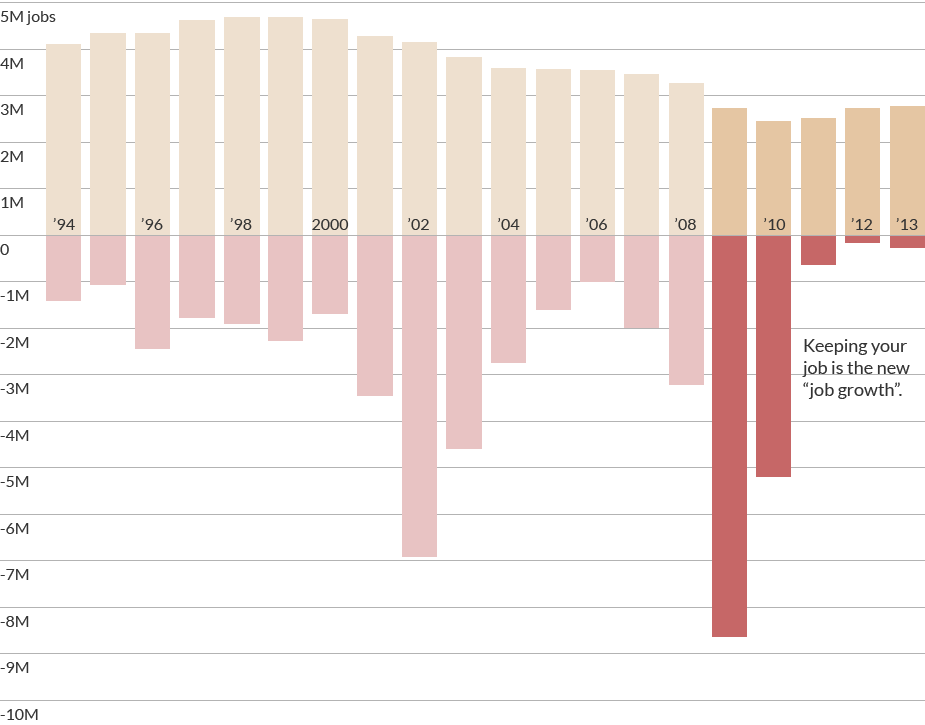

Put these two trends together, and the latest "net job growth" in the U.S. economy actually comes from fewer layoffs — not a major rise in new job creation. That means keeping your job is the new "job growth."

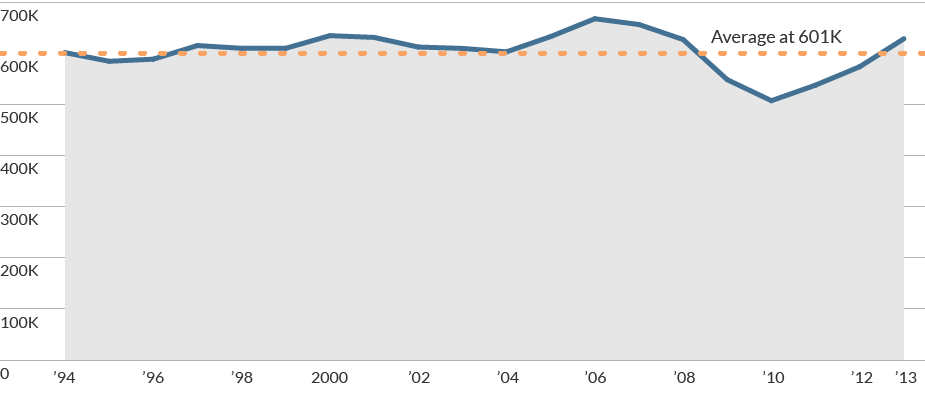

So does the U.S. have an entrepreneurship problem? It doesn't look like it. In fact, creation of new business establishments has been relatively stable over the last 20 years.

But here's the issue: These establishments are hiring fewer workers per firm than they used to, according to the BLS data. Whereas in the 1990s, each new firm hired 7 to 8 workers, now they're hiring just 4 to 5 employees. Firms have become more efficient and are investing more in technology in lieu of labor. "We've seen the substitution of capital for labor," said Janemarie Mulvey, chief economist for the Small Business Administration's Office of Advocacy. "We're moving toward more automation — toward the grocery store self checkout line. It takes fewer workers to make apps. Manufacturing is much more automated. They need fewer workers."

To be clear, new businesses are not necessarily small ones. Even if a new hospital employs hundreds of workers, it would be counted as a new firm in the BLS data.

Likewise, if Wal-Mart opens a new store or Boeing builds a new factory, those too would be counted as "new establishments." Miranda points to separate data collected from the Census Bureau, which characterizes new firms differently. It shows hiring by individual startups has been relatively steady over time, and economists are not sure why the two data sets don't match up.

The overall story, however, is consistent: Hiring by new firms, in aggregate, still dominates U.S. job creation, but not to the extent that it used to. Fewer people are getting laid off by established companies these days (which is great) — but new job creation and investment by new businesses is still far from its heyday.

Note: In the charts above, the 2013 data includes home health aides, whereas data collected before that year excludes this group of workers.

The job market has just started gaining momentum, but that's of little consolation to these Americans. They've been job searching for months with no luck.

Kevin Burgos works full-time, earns more than the minimum wage and even fixes cars on the side to bring in extra money to support his family.

CNN reporters in Tokyo, Abu Dhabi, London and New York look at the state of unemployment around the world.