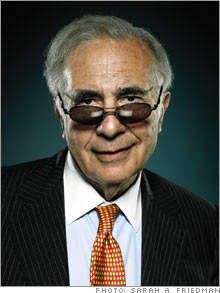

The hottest investor in AmericaFortune's Shawn Tully peers deep inside the brain of Carl Icahn, who now portrays himself as a billionaire Robin Hood, hounding CEOs and enriching shareholders to the tune of $50 billion.(Fortune Magazine) -- Motorola CEO Ed Zander was enjoying a moment of relief from his company's struggles last January, mingling with fellow corporate chieftains at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, when he got the message that makes CEOs see their careers flash before their eyes. The news: Carl Icahn was calling him out. He had bought a 1.4% stake in Motorola and was demanding a seat on the company's board. A few days later Zander made what has become a ritual trip for CEOs caught in Icahn's cross hairs, hastening to the investor's sumptuous offices on the 47th floor of Manhattan's GM Building. The setting is an integral part of the Icahn treatment. CEOs en route to his lair parade past a giant 19th-century watercolor of Napoleon riding to glory over the Russians in the Battle of Friedland, just the sort of rout Icahn covets in his corporate battles.

When Zander arrived, the 71-year-old Icahn ushered him into his immense suite, a paneled aerie overlooking Central Park festooned with museum-quality antiques, portraits of European gentry, and an exquisite portrait by French master Camille Corot. It resembles the drawing room of a British aristocrat, exuding the air of overwhelming wealth and confidence that Icahn - lord of $12 billion in investment capital - summons to bend CEOs to his will. "I told Zander the truth," recalls Icahn. "I said, 'You have a great company. Why did you screw it up?'" After that opening salvo, which Icahn says he delivered in a joshing tone, he mounted his charm offensive. He told Zander that Motorola's (Charts, Fortune 500) stock was vastly undervalued. He proposed that it spend around $12 billion to buy back shares at depressed prices. Icahn said he wasn't particularly interested in serving on Motorola's board, in fact, and would drop his bid for a board seat if Zander would pursue a major buyback. During the conversation Icahn projected a serene sense that he'd mastered the art of enriching shareholders. Says a CEO whose company Icahn targeted: "He thinks his genius is the ability to create value almost instantly." Indeed, Icahn usually succeeds in doing just that. But not this time - not yet. In their meeting Zander said he would discuss an appropriate buyback with the Motorola board. Icahn viewed that as a good sign. But then, six weeks later, a shocking acceleration of Motorola's downturn caught Icahn completely off balance. The company's red-hot RAZR cellphone lost its edge, and the company's phone profits collapsed. Icahn was outraged. "I took Zander at his word" about the cellphone business, says Icahn. "It's incredible that he didn't know how bad things were." A huge buyback became unworkable, as even Icahn admitted, though Motorola did announce a $7.5 billion repurchase plan. Icahn seemed checkmated. But instead of retreating, he cast himself as the shareholders' champion, the enforcer who would hold management to its promise to revive its cellphone business. What started as a pressure tactic turned back into a battle for a board seat in which Icahn showed remarkable credibility with shareholders. On May 9 he lost the proxy vote by a narrow margin. But the outcome was far closer to Friedland than to Waterloo. Icahn took an estimated 45% of the ballots. "I can't remember any activist getting such a big percentage battling a company Motorola's size," says Chris Young, a vice president of ISS, the firm that advises institutions on proxy votes. "The board is now on notice: Either management delivers or they will probably have to go." While Icahn's fight with Motorola has yet to yield the value he thinks investors deserve (his own gain so far: about $50 million), his tenacity and improvisation in this latest chapter illustrate the folly of typecasting him. The rap on Icahn has been that he's a fast-buck artist who uses a limited bag of tricks to give stocks a sharp but often ephemeral boost. In reality Icahn is a complex, versatile figure who has mastered multiple ways of making money. And believe it or not, this former greenmailer, in his fourth decade of dealmaking, may be making more money for shareholders than any other activist on the planet. Whether his prescriptions fit his target companies perfectly is a matter of debate. What's clear is that of all the activists, from Eddie Lampert to Nelson Peltz, it's Icahn who's pursuing the largest number of prominent companies in the widest spectrum of industries, from oil and gas to hotels to pharmaceuticals to real estate to auto parts. Icahn is also taking on bigger prey than anybody else - notably Time Warner (Charts, Fortune 500) (parent of CNNMoney.com and Fortune's publisher) and Motorola - proving almost singlehandedly that a huge market cap is no longer an impenetrable defense. While a New Icahn is taking activism to new heights, the Old Icahn, the outrageous showman, is still at center stage. Icahn remains the most intimidating, the most self-aggrandizing investor in the game, a gangling, 6-foot-3-inch self-proclaimed crusader who, as he quaintly puts it, "takes umbrage" at management's incompetence and responds with a scorched-earth fervor not exactly appreciated by the members of the Business Roundtable. His weaknesses are as outsized as his strengths, especially his penchant for launching shrill personal attacks on CEOs, including Zander. "He's especially good at terrorizing people and wearing down their defenses," says his longtime friend and frequent adversary, the renowned investor Wilbur Ross. "He's the most competitive person I know, and that's saying something." No longer the lone wolf, Icahn is more formidable than ever, having built a team of two dozen associates to help him find targets and mount his crusades. For Fortune's exclusive look inside his kingdom, Icahn, as well as his top dealmakers, sat down for several hours of interviews in which they described the inner workings of an operation that has boosted the total market cap of its target companies by more than $50 billion in just over two years (see chart), spreading the wealth among shareholders far and wide. That's a world removed from the old Carl Icahn, the corporate raider of dark legend. In the 1980s Icahn developed a deservedly lurid reputation as a pioneer of greenmail in raids on companies like B.F. Goodrich. In that odious practice companies rid themselves of rebel intruders like Icahn by buying back the raider's investment at a fat premium, at the expense of the other shareholders. It's not so much that Icahn, for all his posturing about "spoiled CEOs who play too much golf" and "disgraceful country club boards" (with many notable exceptions, he allows), is now more noble. It's that the times and attitudes have radically changed. Greenmail is dead, thanks to changes in corporate charters and state and federal laws. To his credit, Icahn no longer tries to run companies. Most of all, the climate has never been more favorable for Icahn's brand of activism. "The moon and stars are now lined up for activists," says Barry Rosenstein, chief of Jana Partners, the hedge fund that has joined Icahn in fights like his assault on Time Warner. "One reason is that boards are getting a lot more sophisticated. They're far less willing to stand in the way when Carl tries to create shareholder value." It's also that mutual funds are tired of seeing private-equity firms buy troubled public companies and then feast royally by making basic changes the old management could have made itself. "We do the job the LBO guys do, but for all the shareholders," brags Icahn. Most of all, it's the rise of hedge funds that's giving Icahn his new stature. Hedge funds are to today's activism what junk bonds were in the 1980s, only more so. "The hedge funds, unlike a lot of mutual funds, are extremely performance-oriented," says Icahn. "They're far more willing to vote against management." When Icahn attacks a company, hedge funds typically flood in behind him - witness how Highfields Capital, Tudor Investment, and others followed his lead into Motorola stock. According to Icahn, the hedge funds would rather let the old veteran do the gritty work. "It's still not easy running a proxy battle with the company's machinery all lined up against you," says Icahn. Indeed, Icahn claims it's what he calls his "brand name," the perception that he can't be intimidated and won't go away, that gives him his power as an activist. Med-school dropout While Icahn's name is now synonymous with titanic corporate battles, the Queens, N.Y., native seemed at first to be heading for a peaceful career as a teacher or doctor, earning a degree in philosophy at Princeton and attending medical school before dropping out to pursue arbitrage on Wall Street. During the 1980s he made a fortune for himself in his forays against companies ranging from American Can to Uniroyal (and profits for shareholders too in the case of Texaco and, later, RJR Nabisco), despite a few high-profile misses. But it wasn't until recent years that Icahn began assembling the infrastructure he has now, with three main investment vehicles. One of them is his hedge fund, Icahn Partners, created in late 2004. It now manages about $7 billion, of which $1.5 billion is Icahn's money. (Icahn also puts an additional 20% of his own money, outside the fund, into every stock that Icahn Partners purchases. This personal "mirror fund" now totals $1.7 billion.) The management fund is for big players - university endowments, pension funds, and wealthy individuals who invest a minimum of $25 million. Costs are steep: The annual fee is 2.5%, vs. the standard 2%, and Icahn keeps 25% of the gains, compared with the usual 20%. The fund does the type of investing Icahn is renowned for: It takes minority stakes in public companies and typically pushes for change, often threatening a proxy battle. The idea is to make a quick fix - a big stock buyback, asset spinoffs, ousting the CEO - to give the stock at the very least a pop and often lasting gains. Icahn's second vehicle is a holding company called American Real Estate Partners (AREP), essentially a publicly traded private-equity firm. Despite its name, it's a miniconglomerate that buys entire companies and holds them for a long period, often six or seven years. The idea is to purchase beaten-down assets that nobody else wants, usually out of bankruptcy, then fix them up and sell them when they're back in favor, a strategy Icahn has followed from bust to boom in real estate, casinos, and energy. That's not quite all. In what amounts to a third vehicle, Icahn owns personal stakes totaling more than $5 billion in ARI, a railcar manufacturer; Federal-Mogul, a bankrupt auto-parts maker; and Philip Services, a metals-recycling company. He also owns controlling stakes in ImClone (Charts), the scandal-scarred cancer-drug maker, and XO Communications, a telecom service provider. So how are Icahn's investments performing? In its less-than-three-year existence, Icahn Partners has posted annualized gains of 40%, investors told Fortune. After fees, the investors pocketed 28%. That 40% gain trounces the S&P 500's return of around 13%, as well as the 12% for all hedge funds calculated by research firm HedgeFund.net. Icahn Partners boasts a string of big wins in short periods. The acquisition of energy producer Kerr-McGee gave the fund a $300 million gain, or a 100% return in just nine months. Icahn Partners achieved gains of $100 million and $230 million, respectively, both in less than three months, on forcing the sales of Fairmont Hotels & Resorts and drugmaker MedImmune. AREP's performance is even more stellar. Since November 2004, its stock has jumped from $22 to $87, generating $4 billion in value for shareholders. This year AREP (Charts) cashed in on the rampaging values for casinos (Stratosphere Las Vegas and three others) and energy (National Energy Group); it sold both businesses for six times what it had invested in the late 1990s, netting over $2 billion. |

Sponsors

|