|

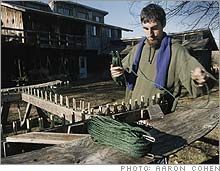

Capitalist pain hits a hammock commune

A throwback hippie collective in Virginia copes with the loss of its biggest customer, Pier 1 Imports.

(FORTUNE Small Business Magazine) - Twin Oaks is experiencing a midlife crisis. The Virginia commune supported its throwback hippie lifestyle for more than 38 years by selling hammocks and tofu. But in 2004, Twin Oaks lost one of its biggest hammock customers, Pier 1 Imports (Research). Last year revenues slipped to $1.1 million from a 2000 peak of more than $2 million. And expenses such as gas and health care for the commune's aging population are climbing fast. "I hoped we would be financially secure by now," says founder Kat Kinkade, 75. "We're not."

Kinkade and seven other dreamers launched Twin Oaks on 69 acres of rolling Virginia farmland that they bought for $26,500 in 1967. (Today the commune owns 450 acres.) Like many other idealistic, left-leaning young Americans in those days, they hoped to escape the political and social tumult of the 1960s by forming a self-sustaining rural community. Since then hundreds of dropouts, drifters, and seekers have passed through Twin Oaks. "A lot of people come here searching for something," says Kinkade, who worked as a secretary before she left the outside world behind. Alternative wages

Members are expected to work around 40 hours a week. All jobs are compensated equally, whether in the hammock shop, kitchen, or garden. Residents earn a stipend of around $2 a day. Cheap labor allows the commune to price its products competitively. But members reject suggestions that Twin Oaks is the hippie equivalent of a Sri Lankan sweatshop. "We work for a lifestyle, not a wage," says Thea, 35, a mother with dreadlocks who follows the Twin Oaks custom of not using a last name. Twin Oaks is a collective: Although volunteer managers are responsible for making the business decisions, all members have a say. Most don't aspire to join the managerial ranks. "You don't get more money or a bigger room being a manager, just more of a headache," says Apple, 32, who joined the commune in 2003 and works in the tofu hut, among other places. Like many a small business before it, Twin Oaks recently learned the painful lesson that relying on one big customer can be dangerous to your economic health. By the mid-1990s, Pier 1 accounted for $700,000 in annual revenue, about 70% of the commune's total. In 1998, Pier 1 scaled back its contract by 30%. Sales grew for a few years, but in 2004 the giant retailer stopped buying. "Pier 1 was a boon to the community," says Kathryn, a 29-year-old manager in the hammock business. "For a lot of us, losing them was also kind of exciting - no more working for a multinational. But now we really have to deal with what we want to be as a business." Direct-to-consumer distribution

Twin Oaks has been in austerity mode since 2004. Last year the commune's annual budget was slashed by around 20%. Individual work quotas rose to 44 hours a week from 42, and the monthly allowance dropped to $61 from $71, forcing some members to give up small luxuries such as coffee and wine. Manager Tom, 40, says that Twin Oaks hopes to reduce its dependence on big retail partners by selling hammocks to consumers via direct mail and eBay. "We'll get a lot more money per item for less work," he predicts hopefully. The managers also hope to snag more small retail partners such as Northern Lights Hammocks in Provincetown, Mass. Owner "T" Gandolfo says he has been buying hammocks from Twin Oaks for the past 25 years because he has a voice in product development, and he can always get a manager on the phone. "They're humanistic and reliable," he says. Other members argue that salvation lies in ramping up Twin Oaks tofu. Sales for its 13 flavors more than doubled last year, to $250,000, thanks mainly to a big new client, Sunergia, a soy-foods company based in Charlottesville, Va. There has been talk of expanding the bedroom-sized tofu hut and launching an aggressive sales push. But most communards are not natural salesmen. And the tofu hut is a literal sweatshop: hot, damp, and factory-like. The tofu managers have had a hard time persuading residents to pick up the extra shifts that are needed to expand production. There's concern that the communal culture will change if members are pushed into the scheduled, repetitive, money-oriented labor that many of them joined Twin Oaks to escape. If that happens, some residents will probably move on. Kat Kinkade is unfazed. "We set this up so no one would kill it," she says, lounging in a magenta housedress on a common-room couch with two other female residents, one 29 and the other 83. Members come and go, Kinkade suggests, but Twin Oaks goes on forever. ______________________________ 50 small cap stocks to watch. See the list.

Retire rich:Keep out the taxman |

|